Archives Hub feature for March 2019

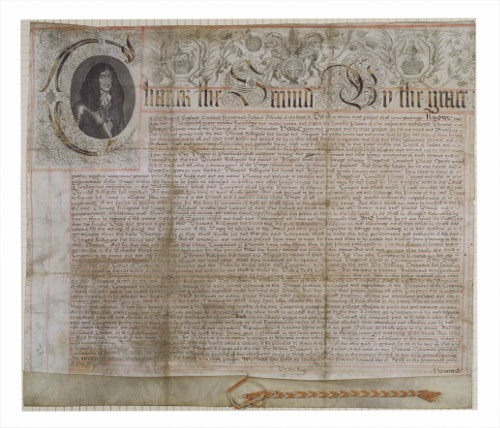

The Devonshire Collection Archives held at Chatsworth span over 450 years and date back to the time of Elizabeth Talbot, Countess of Shrewsbury (c.1527-1708, better known as Bess of Hardwick), with elements of the archive dating from even earlier. They document the lives, careers and estate management of the Cavendish family – one of the most important aristocratic families in English history, counting amongst its number politicians, art connoisseurs and collectors, industrialists, and leading society figures.

Filling over 6,000 boxes, the archives can be divided broadly into estate and family papers. The family papers comprise the personal archives of many of the Dukes and Duchesses of Devonshire, other family members, families who married into the Cavendish line, and some individuals who had a close association with the family, such as the philosopher Thomas Hobbes, and the landscape gardener and architect Sir Joseph Paxton.

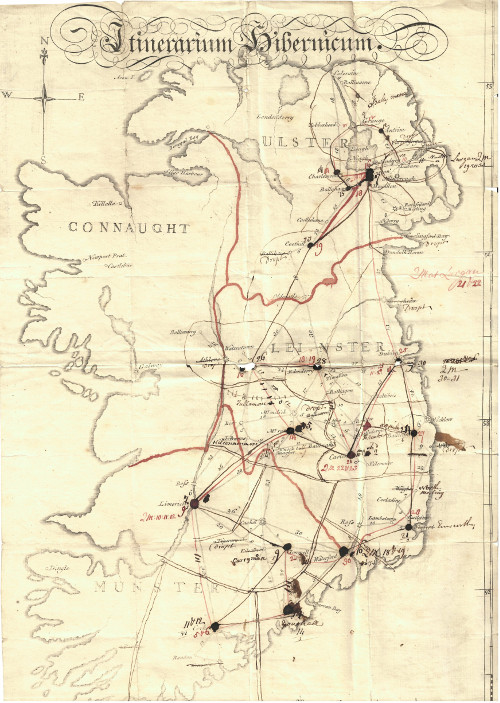

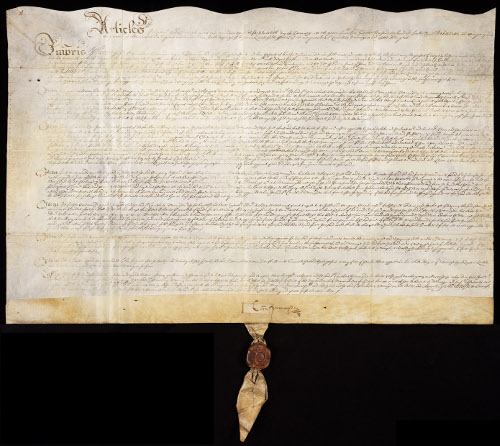

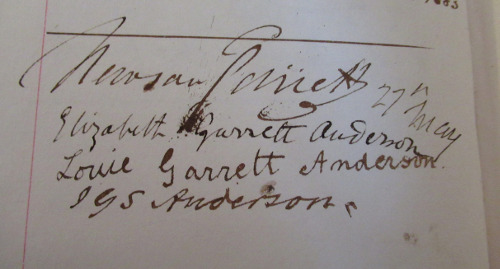

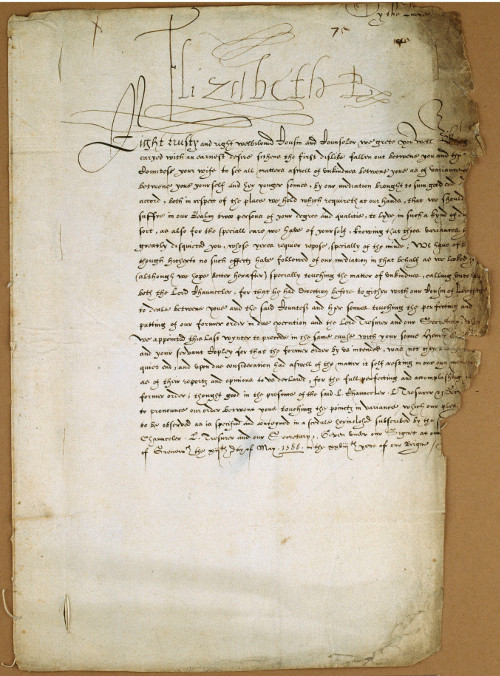

Sorting and listing of the family correspondence began in the 1920s, resulting in several extremely large series of correspondence focused on chronological or specific ducal periods. However, our first submissions to the Archives Hub – published this month – focus primarily on a separate group of smaller archives known as the ‘Devonshire Family Collections’. These predominantly date from the late 18th to the early 20th centuries, although they do contain some much earlier material – notably in the form of papers relating to the marital dispute between Bess of Hardwick and her fourth husband George Talbot, 6th Earl of Shrewsbury. Money and property played a major role in this dispute, but the rift between husband and wife was exacerbated by Shrewsbury’s role as custodian of Mary Queen of Scots for 15 years. So notable were the couple involved that Queen Elizabeth I herself intervened in an attempt to reconcile husband and wife – although this ultimately had little effect.

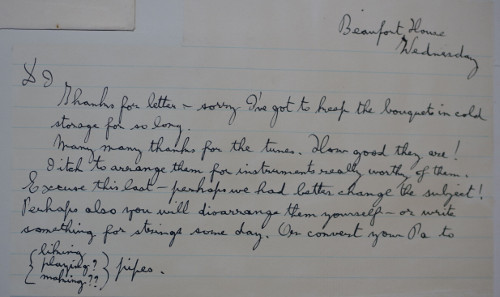

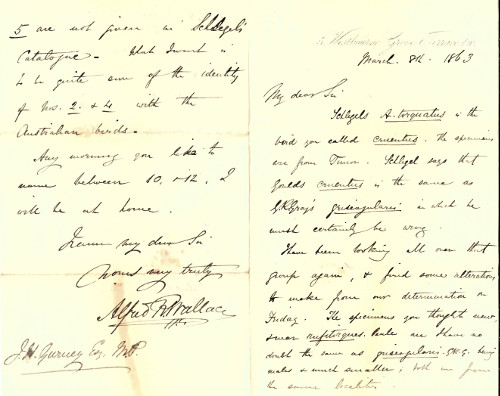

From the 18th and 19th centuries, there are extensive networks of family correspondence. Letters were exchanged between family members in the UK – between those resident at or moving between different properties and estates, between city and country, and between parents and children at school. Letters also crossed continents as a crucial means of keeping in touch when family members were travelling or working abroad: there are letters home from family members undertaking the continental Grand Tour in the eighteenth century; letters from William Cavendish, 7th Duke of Devonshire, sent home from an American trip in 1859; and – from the same writer as a much younger man – some wonderfully detailed letters sent to his mother from Russia in 1826, where he accompanied the 6th Duke of Devonshire to attend the coronation of Tsar Nicholas I. Amongst descriptions of palaces, country houses, working mills, customs and language, the voice of an 18-year-old also shines through: in one letter he remarks rather wearily that he hopes when they get to Moscow they will not have to look at any more relics of Peter the Great as they have seen so many already.

Cavendish family members served for centuries as MPs in the Whig and Liberal cause, so there is extensive political correspondence amongst the family papers. The papers of Spencer Compton Cavendish, the 8th Duke (better known throughout his political career as the Marquess of Hartington) include letters from W.E. Gladstone amongst others. His wife’s papers (Louise Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire) contain letters of condolence she received on his death, including one from a young Winston Churchill expressing his gratitude for having had an opportunity to work with the 8th Duke. Also notable are the papers of the 8th Duke’s brother, Lord Frederick Cavendish (1836-82), which contain references to the 1867 Reform Act, industrial reform, education and much more. There are also posthumous papers relating to his death in a politically-motivated murder in Phoenix Park, Dublin, in 1882.

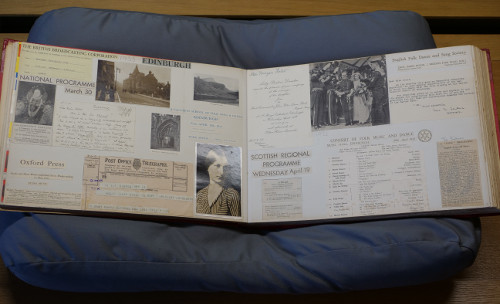

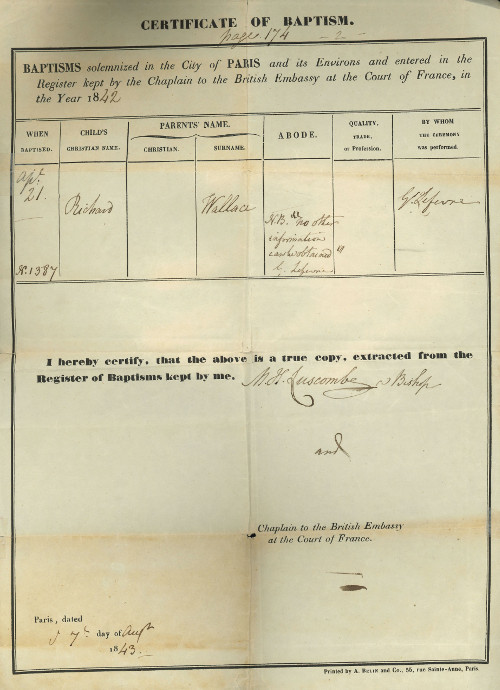

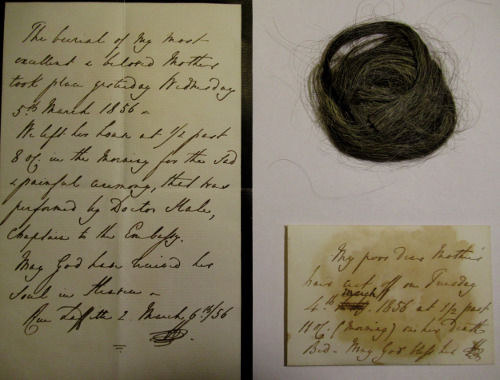

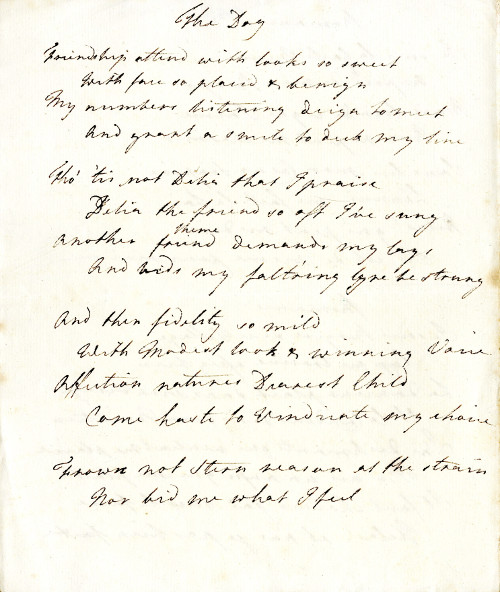

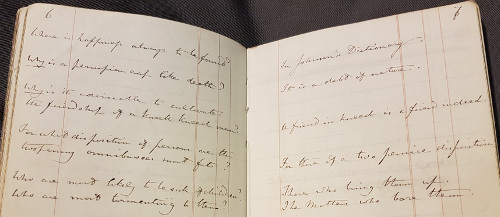

In addition to letters, there are diaries of various family members, including one documenting the 4th Duke of Devonshire’s Grand Tour in 1739-40; scrapbooks and commonplace books – including some compiled by Duchess Georgiana (1757-1806), whose papers also contain some of her own literary manuscripts; personal and household accounts; official documents; and keepsakes and mementoes such as locks of hair treasured by parents and spouses in memory of lost family members.

23 March-6 October 2019.

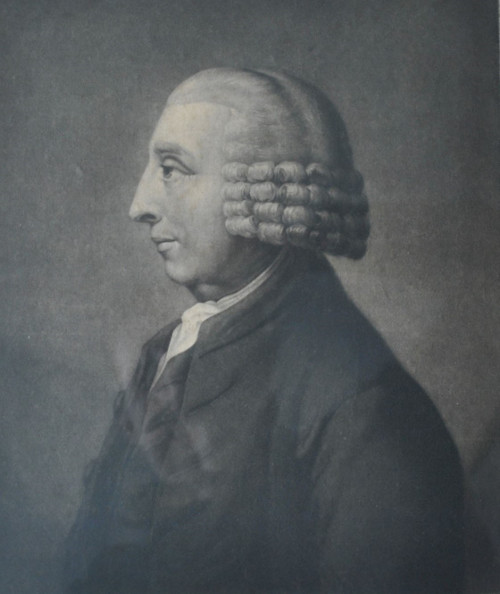

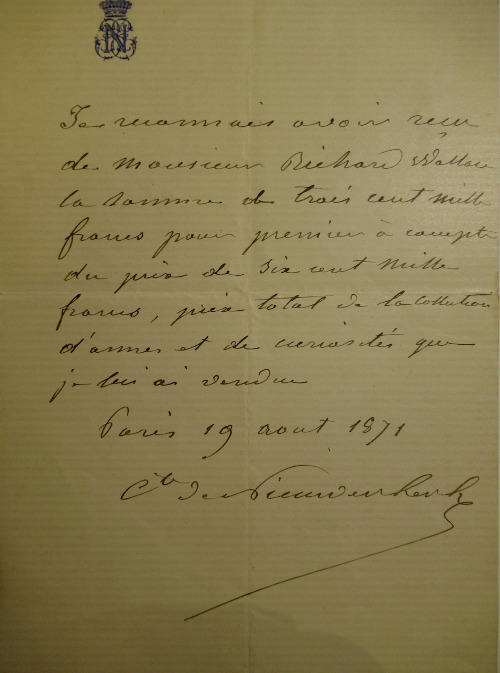

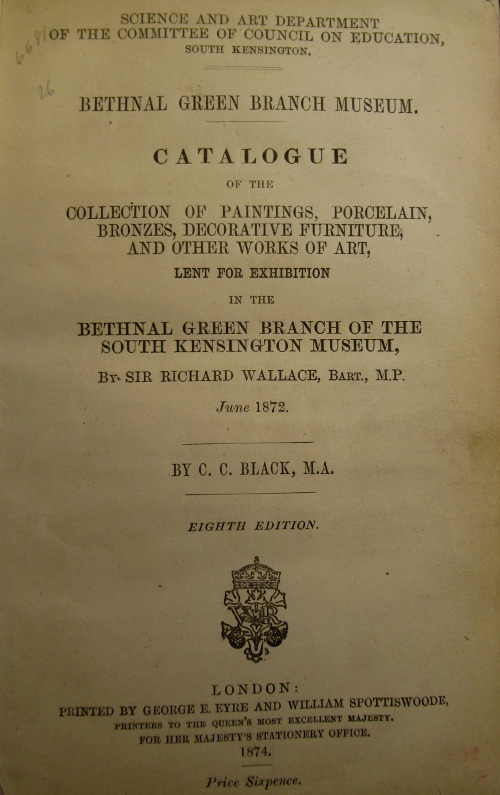

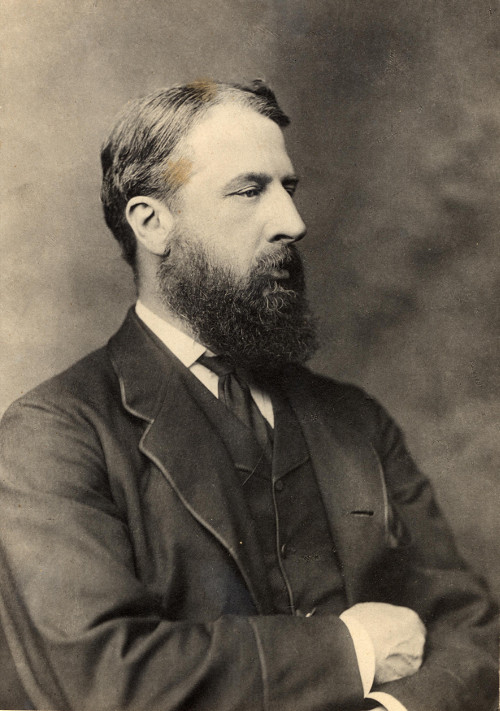

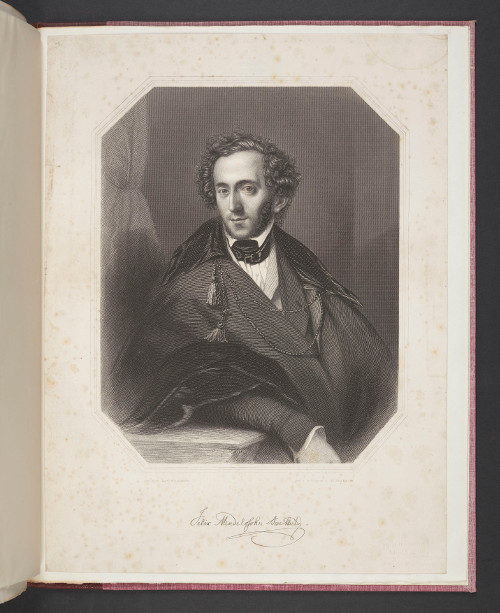

Special mention must be made of William George Spencer Cavendish, 6th Duke of Devonshire (1790-1858). An art collector and bibliophile who loved entertaining and travel, he was also responsible for transforming Chatsworth through the addition of the great North Wing and his support of Joseph Paxton’s innovative work in the gardens. As so many of the family collections date from the 19th century, he and his activities feature in many of them.

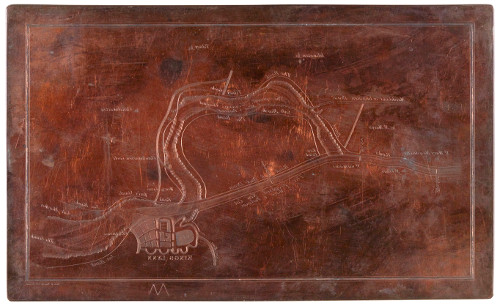

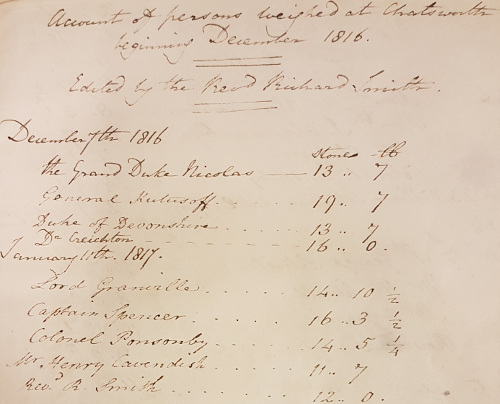

The 6th Duke also had a great archival sensibility and his own papers are particularly rich: significant trips, visits or activities are meticulously recorded in scrapbooks containing letters, cuttings, tickets, invitations, calling cards and other printed ephemera (Papers of William George Spencer Cavendish, 6th Duke of Devonshire). Alongside journals, diaries and notebooks, he also kept yearly datebooks detailing places he visited. A great socialiser, he recorded lists of acquaintances as well as keeping guest books and visitors’ books.

There are also the manuscript and proofs of his Handbook to Chatsworth and Hardwick (1844), which stands the test of time as an engaging and accessible guide book to his two principal houses; his writing was admired by Charles Dickens, who read his copy of the Handbook on a train journey back to London after visiting the 6th Duke at Chatsworth and commented that the writing was worthy of a novelist.

Most of the family collections now have item-level catalogues available in PDF form via the Chatsworth website. Many of the other, larger, collections have item-level lists in various states and formats which can be provided on request. We will be submitting further collection-level descriptions to the Archives Hub in due course.

Fran Baker

Archivist & Librarian

Chatsworth

Related

Browse all Devonshire Collection Archives, Chatsworth descriptions available to date on the Archives Hub.

The Dog: A celebration at Chatsworth

Exhibition: 23 March – 6 October 2019

All images copyright Chatsworth House Trust and reproduced with the kind permission of the copyright holders.

![Photograph of an early ‘floating institute’ operated by the Missions to Seamen, late 19th century [U DMS].](https://blog.archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/01/seam_institute.jpg)

![Logo of the Flying Angel [U DMS].](https://blog.archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/01/seam_angel.jpg)

![Logo of the Stella Maris [U DAPS/12/4].](https://blog.archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/01/seam_stella.jpg)

![Photograph of the interior of the original Apostleship of the Sea house in Glasgow, c.1920s [U DAPS/7/2].](https://blog.archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/01/seam_house.jpg)

![Photograph of a visit paid to Bishop Rock lighthouse by Missions to Seamen representatives for the Scilly Isles [U DMS].](https://blog.archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/01/seam_visit.jpg)