Archives Hub feature for August 2021

In 2018 De Montfort University (DMU) Special Collections received a grant from the Wellcome Trust to undertake a cataloguing project involving four of our sports history collections: the papers of England Boxing, the Ski Club of Great Britain, Sir Norman Chester and the Special Olympics Leicester. In this feature project cataloguer Louise Bruton focuses on the particular challenges of cataloguing one of those collections: the papers of Sir Norman Chester, an academic and specialist in public administration by profession as well as a lifelong football supporter.

Cataloguing personal papers as opposed to those of an organisation can be challenging. Whereas the documents of an organisation often retain the traces of the creating administration, divided into departments and divisions with defined responsibilities, personal papers can be more amorphous. The challenge presented by the Chester files was that they all consisted of papers relating to football improvement works and the content of each file appeared at first glance to be very similar. With over 300 files to sort through, I needed a way to uncover each file’s history and make sure that I retained its association to other files documenting the same piece of work.

I discovered that the best way to distinguish between files was to establish what Chester’s role was in that particular file – was he Chairman, Deputy Chairman, advisor, individual football fan? The way he signed off his letters was a clue, as was the headed paper. Chester’s papers were split and given to different institutions, so this section of his papers is entirely concerned with his work on football administration and I therefore decided that the best way to structure the catalogue was by Chester’s role.

Chester led two inquiries into the organisation, finance and management of association football in 1966 – 1968 and 1982 – 1983, the former only a few years after the end of the retain and transfer system and maximum wage rule which determined players’ ability to transfer between clubs, and the latter only ten years before the creation of the Premier League. The Chester Papers collection includes files of correspondence and notes Chester compiled as he worked on these inquiries, along with copies of the final reports (see series S/005/01 and S/005/02).

Chester was working during a difficult time for football in which declining attendance figures, crowd behaviour, financial struggles and stadium safety were key concerns. The bulk of the collection we hold consists of files relating to Chester’s work for two Trusts which sought to improve facilities at football grounds across Britain.

Appointed for his unique combination of public administration expertise and personal passion for the game, Chester served as Chairman of The Football Grounds Improvement Trust from 1975 – 1979 and as Deputy Chairman of The Football Trust from 1979 – 1986. Following the Ibrox Stadium Disaster in 1971, a report into safety at sports grounds found that existing standards were inadequate. The Safety of Sports Grounds Act 1975 required sports stadia with capacities of over 10,000 to carry out improvements to meet new safety criteria. Many Football League club grounds were large enough to fall under the legislation, but found it difficult to finance the necessary alterations.

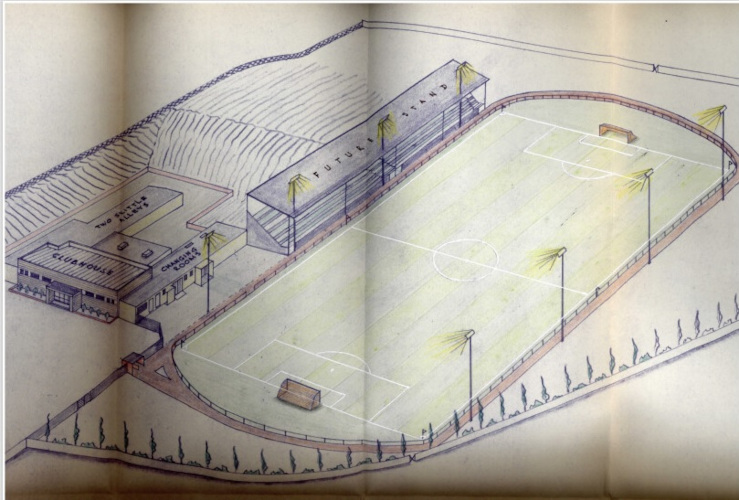

The Football Grounds Improvement Trust (FGIT) was set up to give grants to football clubs to carry out safety improvement works. Funded by money from the football pools, FGIT considered applications from clubs on an individual basis, using a firm of surveyors to examine the technical details of proposed structural work. As Chairman, Chester reviewed all of these applications and kept copies, along with correspondence, in a series of alphabetised files. These are now catalogued as the series S/005/03/04. Many of the applications include plans and provide a snapshot each club’s facilities and future plans at that moment in time. Sadly, in spite of the grants allocated and the improvements made, disasters such as the Bradford City stadium fire in 1985 showed that many football grounds still required significant redevelopment.

Grant applications can also be found in Chester’s files relating to his work as Deputy Chairman of The Football Trust. As a sister organisation to FGIT, the Football Trust had a wider remit, extending grants to non-League football clubs and supporting research into football’s place in society. The grant files series (S/005/04/05) is a great place to search for local clubs as well as local-authority run grass-roots football grounds.

Chester’s files show that work to improve the safety of football stadia was linked to a desire to improve the environment for spectators and to contribute to a reduction in hooliganism. The ‘Anti-Hooliganism Measures’ series (S/005/04/05/009) documents efforts to understand and tackle problematic crowd behaviour. This work was ongoing at the time of Chester’s death in 1986.

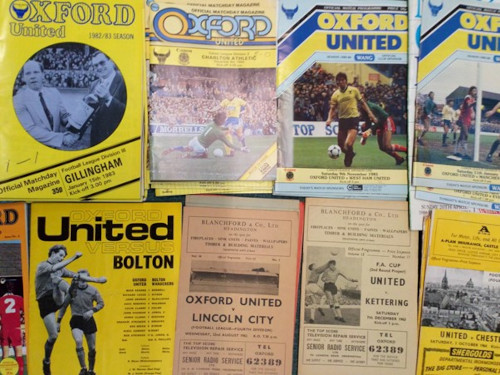

The most personal items are his collection of Oxford United football programmes. Many are annotated with the final score, showing that Chester attended almost all of his local team’s home games over a twenty-year period until the month before he died, remaining a football fan first and a football administrator second.

Louise Bruton, Project Archivist

and Katharine Short, Special Collections Manager

‘Unboxing the Boxer’ Wellcome Trust funded cataloguing project

De Montfort University Archives and Special Collections

Related

The rest of Chester’s papers are held by Nuffield College Archives, University of Oxford where Chester worked for most of his life: Papers of Sir Norman Chester, 1907–1986.

Papers of England Boxing (formerly Amateur Boxing Association of England), 1880-2016

Special Olympics Leicester, 2009

Browse all De Montfort University Archives and Special Collections on the Archives Hub.

Browse more Football collections on the Archives Hub.

All images copyright De Montfort University Archives and Special Collections. Reproduced with the kind permission of the copyright holders.