Archives Hub feature for March 2024

The Thackray Museum of Medicine houses an incredible collection of 50,000 objects and 25,000 books, journals and catalogues, and the collections focus on responses to people’s medical and healthcare needs – the innovation, enterprise, technology and collective effort to make us well. But it is also home to several gifted medical archives, over 200 of which have remained largely unexplored until now. Since November 2022, the Thackray Museum of Medicine has begun to catalogue its archive through appointing a qualified archivist for the first time, and with the help of volunteers, over 100 collections have been catalogued and made available on the Thackray Museum’s online catalogue.

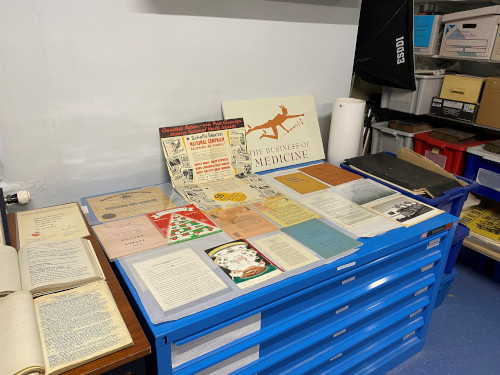

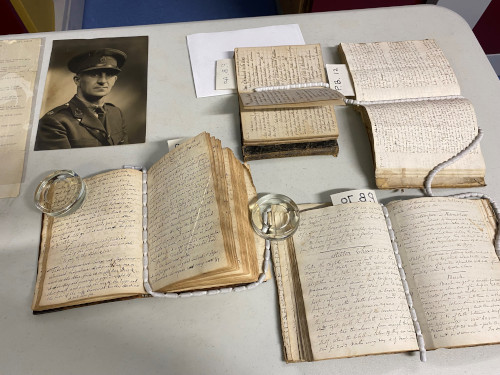

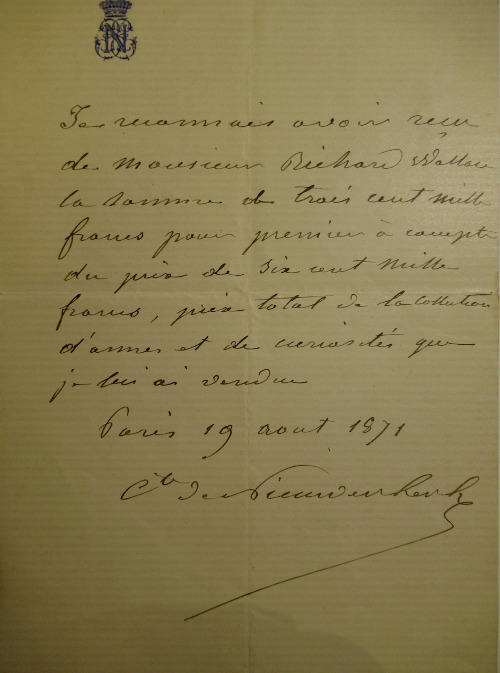

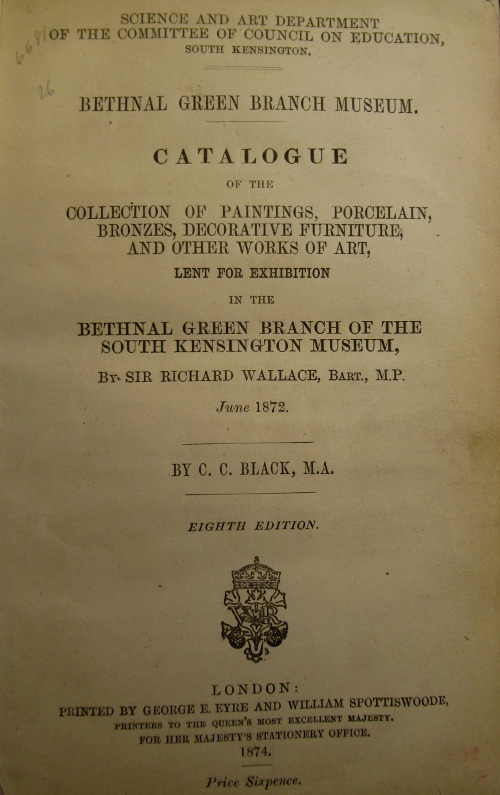

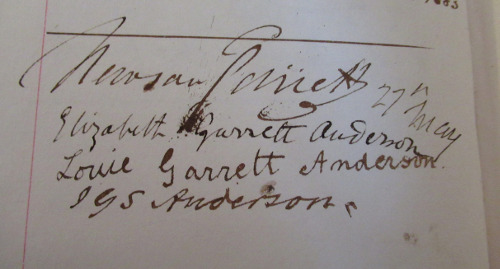

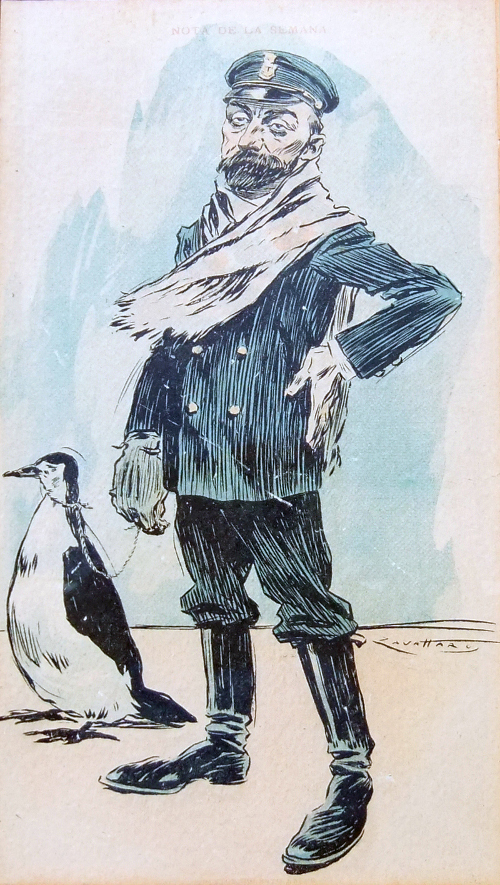

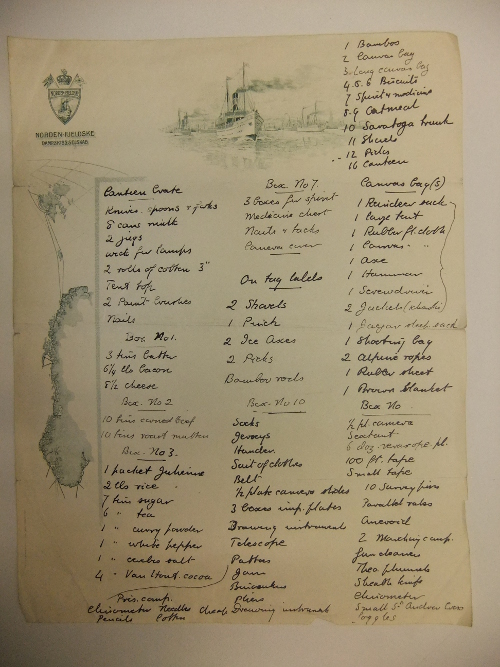

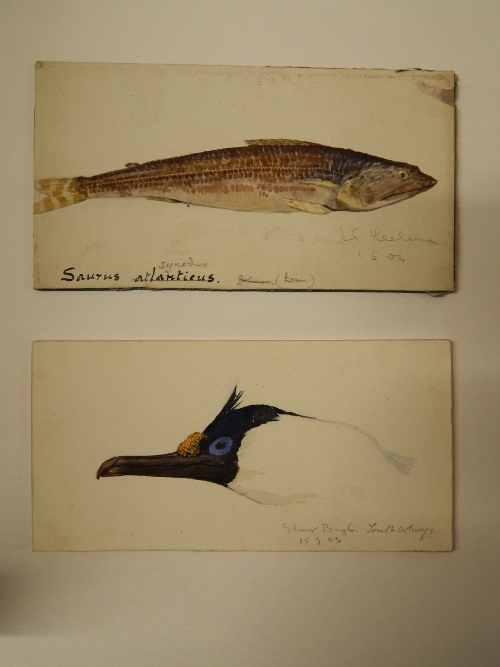

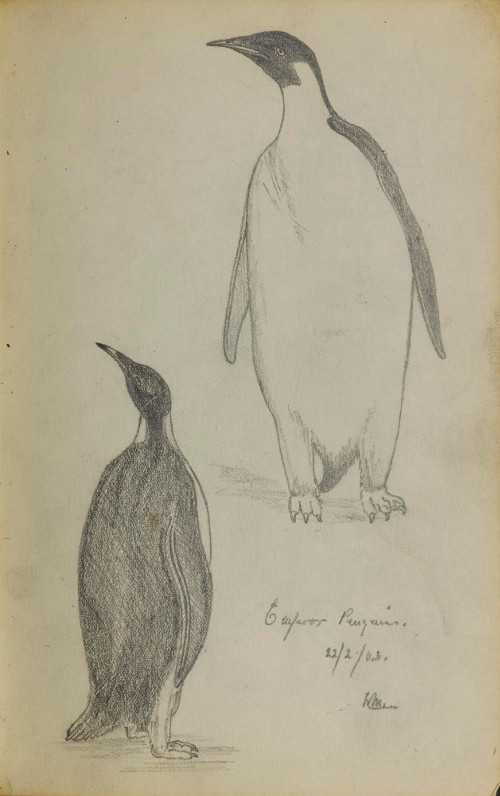

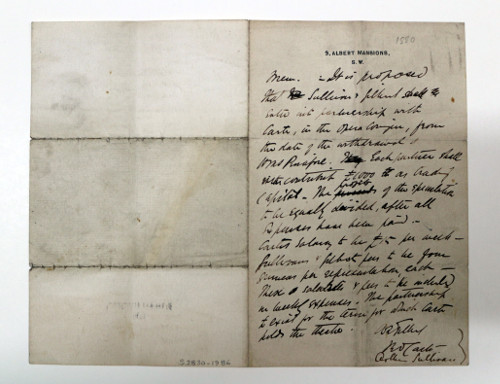

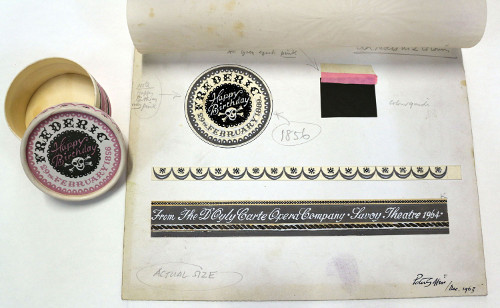

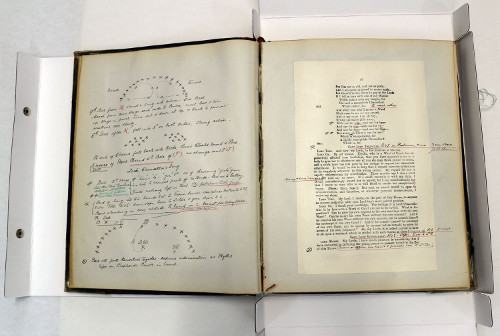

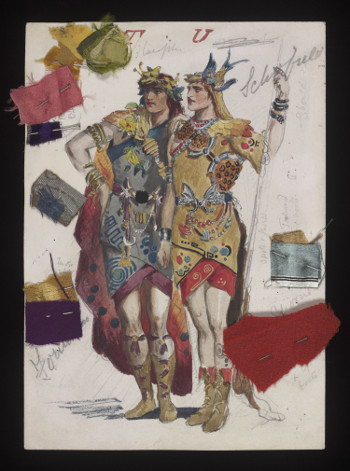

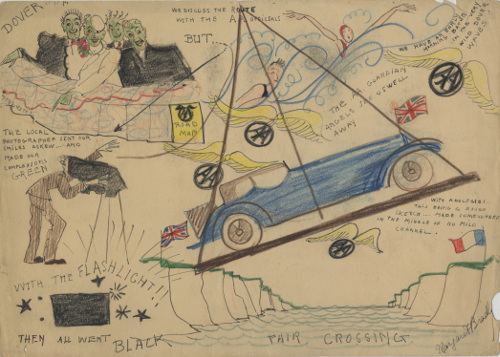

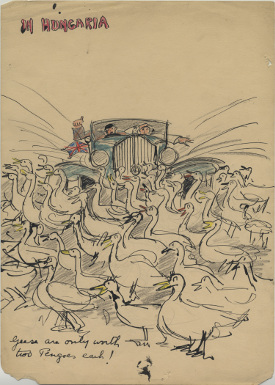

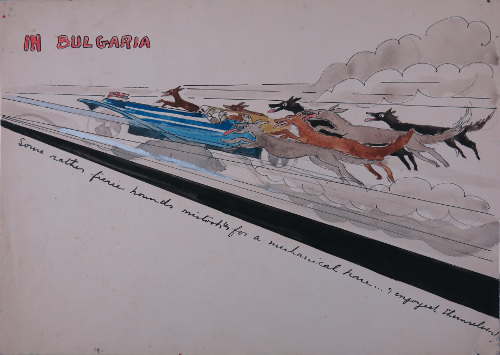

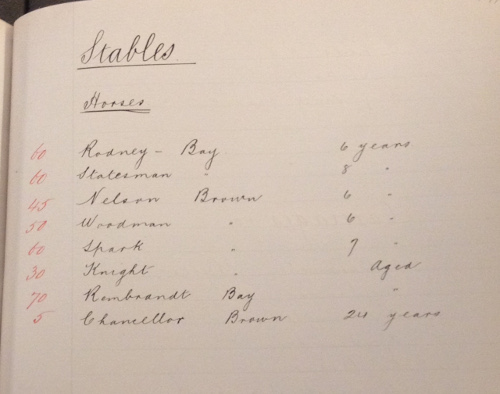

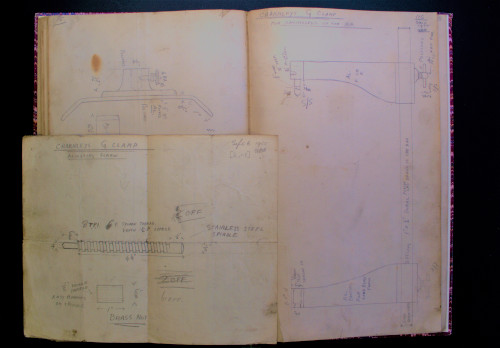

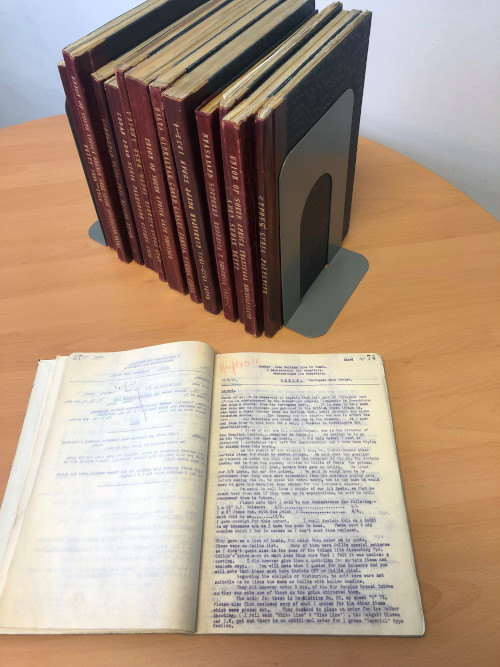

The primary focus of the archival collections is the medical supply trade, particularly surgical instrument makers. The first items to be acquired, and the most significant, were the company archive of Chas. F. Thackray, the former Leeds-based medical supplies company, the success of which ultimately paved the way for the museum to be established in 1997. The Thackray Company archive covers the life of the firm from 1902-1990 and contains items such as trade catalogues, press cuttings, surgical instrument drawings and a unique series of notebooks compiled by Thackray representatives who travelled to countries across the world to sell medical equipment and to perform fact-finding missions into these countries’ medical capabilities.

There are two reasons the collection stands out. Firstly, the collection contains a unique series of notebooks compiled by Thackray representatives who travelled to countries across the world to sell medical equipment, and to perform fact-finding missions into these countries’ medical capabilities. It provides insight into the medical practices of different countries during the 1930s and describes their prowess in using technology. Secondly, as the Thackray Company worked with Sir John Charnley, the founder of modern hip replacements, from 1947 onwards to design instruments for hip surgery – work which helped hundreds of thousands of people around the world – this collection would be of interest to NHS communities and voices from the wider public who have had experience of hip replacements, and researchers of the subject. The Thackray Company archive is one of two large collections held in our archives; the other is that of the Oxford Knee archive, a business archive which relates to the development of the Oxford Partial Knee implant 40 years ago, the invention of which revolutionised orthopaedic surgery and became one of the most successful knee replacements in the world.

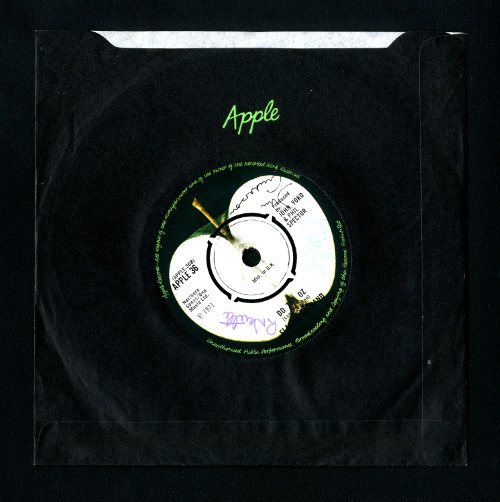

Our archive also holds a collection relating to Dr Scholl’s foot company, a company that you may have seen advertised while visiting Boots and/or shoe shops. Our collection of Scholl material includes the founder, William Matias Scholl’s certificate qualifying him as a physician and surgeon from the State of Illinois Department, and the collection also contains company magazines between 1929 and 1972 including copies of ‘The Scholl Link’ published for employees in the United Kingdom who served in the war, and a special issue commemorating ‘VE Day’ in May 1945. Other organisational collections catalogued thus far include that of the Calenduline Company – a Chicago-based company that manufactured treatments for the eye and throat; the Eschmann Equipment company, who were pioneers in making operating tables; and the Downs Surgical Limited company – a collection of material relating to a manufacturing company who were pioneers in making high-quality medical instruments, particularly those used in ear, nose and throat surgery.

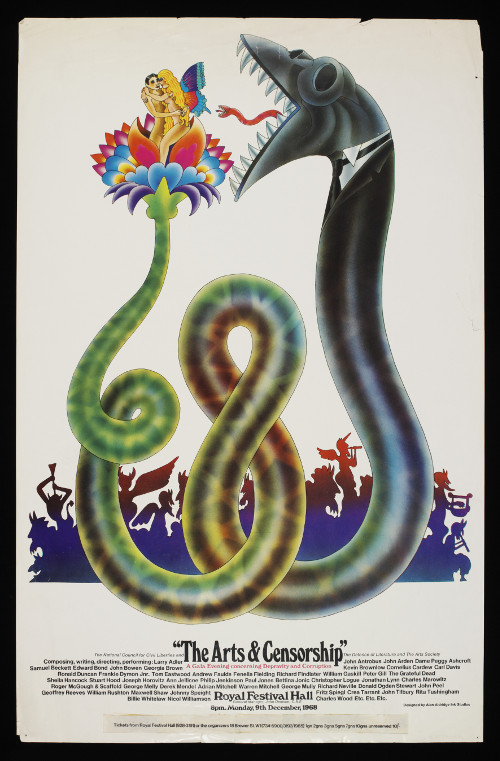

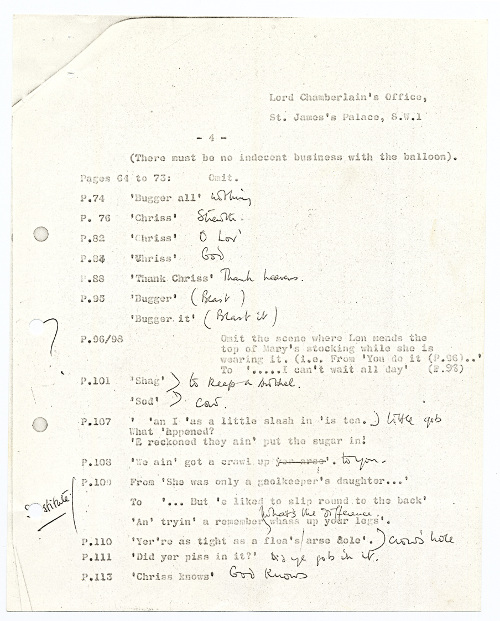

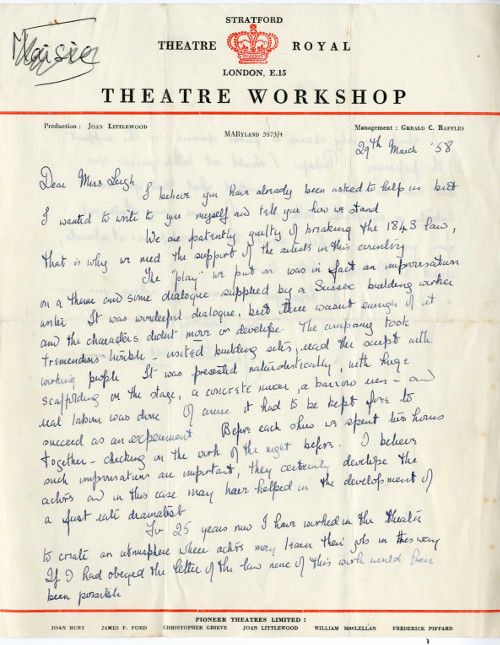

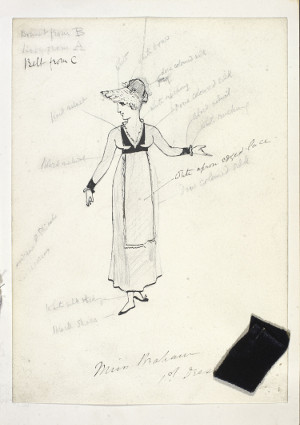

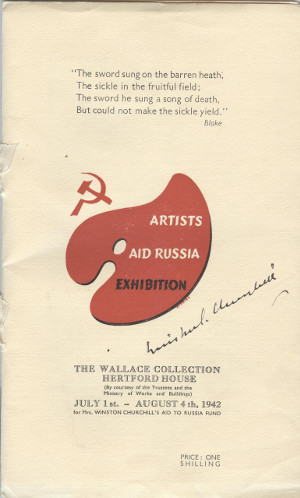

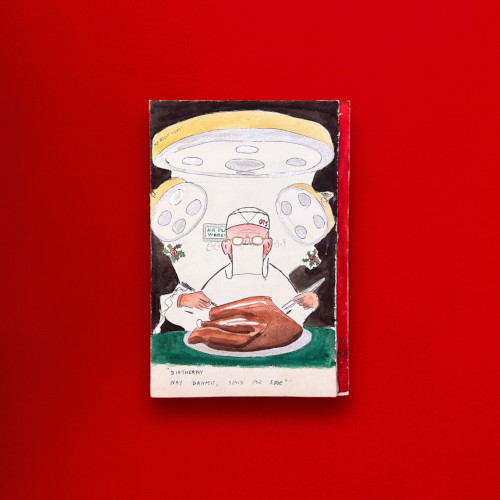

As well as organisations, the museum has acquired many personal papers of local doctors, nurses and surgeons since it opened in 1997, and these have now been catalogued and made available on our website. As an example, this has included the personal papers of Pauline Sellers, who qualified as a nurse in Mirfield and then worked at the Royal Air Force Hospital at Nocton Hall. While at Nocton Hall, Sellers took part in theatre performances and joined Nocton Hall Theatre Group, playing Mrs Wagstaff in the play ‘Dry Rot’. She also accompanied Princess Alexandra on a royal visit in July 1969, showing the Princess around one of the children’s wards. Other collections of personal papers catalogued include the Leeds-based urologist Leslie Pyrah who was the first professor of urology in the United Kingdom and set up the first renal dialysis unit in the UK; the archive of Michael Martin OBE who worked for the Royal National Institute for the Deaf for 35 years; the archive of David Wilson, who worked as a consultant in accident and emergency medicine at Leeds General Infirmary, and the papers of Henry Shucksmith, who was honorary assistant surgeon to the General Infirmary at Leeds and numerous hospitals in the area including St James’s and Seacroft. As well as recording his professional articles on the topics of vascular surgery and breast cancer, I have been able to uncover unusual items in his papers, such as a nice Christmas card with a drawing of a surgeon carving a turkey on the front, sent to him by friends of his from his days serving in the Territorial Army during the Second World War.

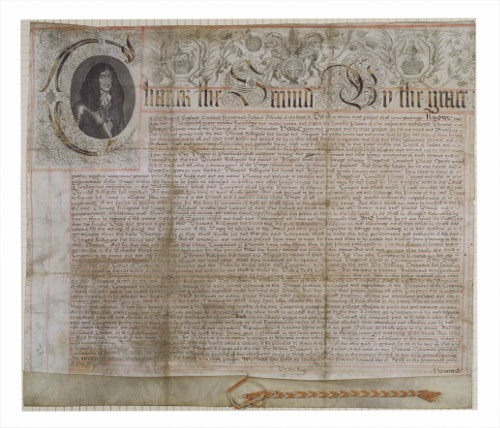

Volunteers have helped to catalogue collections also and two of volunteers, both called Sam, catalogued the collection of Herbert Agar, a Leeds-based surgeon who specialised in obstetrics and gynaecology. They have also contributed to cataloguing prescription books, and books in our archive that contain formulas and recipes for food, drink and ailments, dating back to the 17th century. Despite not having any experience of archival work before they started, volunteers have contributed to cataloguing a dozen collections from the archive thus far, and gained skills in cataloguing, digitisation and basic conservation tasks along the way.

The recipe and formula books are among the most interesting items within the archives and contain recipes for all manner of food, drink and various remedies, including biscuits, Stilton Cheese, toothpaste, fish sauce and ailments for gout and headaches amongst others!

We are constantly cataloguing new collections and placing them onto the Archives Hub as well as our own catalogue regularly, and our collections would be of interest to anyone studying the history of medicine and healthcare. If you are interested in finding out more about our collections, or want to make an appointment to view them, please contact us at collections@thackraymuseum.org

Robert Curphey

Archivist

Thackray Museum of Medicine

Related

Descriptions of other archives held by Thackray Museum of Medicine can be found on Archives Hub here: https://archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/search/locations/da5db37f-9a3b-3538-8901-627a707c8623

All images copyright Thackray Museum of Medicine. Reproduced with the kind permission of the copyright holders.