To mark International Women’s Day on 8th March, here is a selection of archives featuring women who have excelled and been highly influential in many different fields.

Daphne Oram (1925-2003), composer and musician

The Daphne Oram Archive, held at Goldsmiths, University of London, comprises papers, personal research, correspondence and photographs documenting the life and work of a pioneering British composer and electronic musician.

Throughout her career she lectured on electronic music and studio techniques. In 1971 she wrote An Individual Note of Music, Sound and Electronics which investigated philosophical aspects of electronic music. Besides being a musical innovator her other significant achievements include being the first woman to direct an electronic music studio, the first woman to set up a personal studio and the first woman to design and construct an electronic musical instrument.

Delia Derbyshire (1937-2001), musician and composer

The University of Manchester holds the Papers of Delia Derbyshire, composer. After being rejected by Decca Records, who said that they did not employ women in the recording studio, in 1962 Derbyshire became a trainee studio manager at the BBC. She was soon seconded to work at the BBC’s Radiophonic Workshop, which had been set up to provide theme and incidental music and sound for BBC radio and television programmes. The following year, she produced her electronic ‘realisation’ of Ron Grainer’s theme tune for the hugely popular BBC series Doctor Who – which is still one of the most famous and instantly recognisable television themes. In the late 1990s there was renewed interest in her work and many younger musicians making electronic dance and ambient music (such as Aphex Twin and The Chemical Brothers) cited Derbyshire as an important influence.

The Anita White Foundation International Women and Sport Archive

Dr Anita White and Professor Celia Brackenridge were both associated with the University of Chichester, and they were both centrally involved in the leadership and development of the international women and sport movement since 1990. The International Women and Sport Archive is comprised primarily of papers brought together by them and other leaders in the movement, accumulated in the course of their research, study and work in the fields of the sociology of sport and sport science, and their involvement as activists and leaders in the global women and sport movement.

The International Women and Sport Movement is said to have been born out of a decade in which increasing globalisation brought together women from across the world in the practice of sport. It does not refer to any one organisation, body or country, but it is generally agreed that a landmark event and major catalyst in the movement was the first international conference on women and sport which took place on 5-8 May 1994.

Kaye Webb ( 1914-1996), editor and publisher

The Papers of Kaye Webb, covering her career as journalist, magazine editor, editor at Puffin and later literary agent, are held at the Seven Stories Archive. The collection provides a comprehensive record of Webb’s career, reflecting the wide variety of work undertaken by her, and documented through notes, correspondence, press cuttings, audio-visual material, memorabilia and ephemera. Webb was editor of Puffin Books between 1961 and 1979, and in 1967 founded the Puffin Club, which she ran until 1981. As a journalist she worked on publications including Picture Post, Lilliput and the News Chronicle.

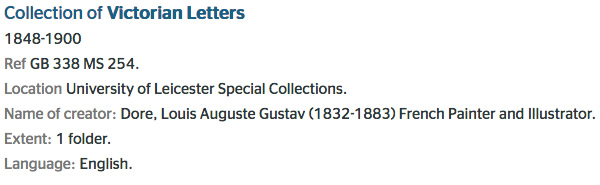

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (1836-1917), physician and suffragist

The Letters of Elizabeth Garrett Anderson are part of the Women’s Library Archives. An English physician and suffragist, she was was the first woman to qualify in Britain as a physician and surgeon. She was the co-founder of the first hospital staffed by women, the first dean of a British medical school, the first woman in Britain to be elected to a school board and, as mayor of Aldeburgh, the first female mayor in Britain. The letters cover Anderson’s struggle to secure an entry into the medical profession.

Barbara Castle (1910-2002), politician and campaigner

The Barbara Castle Cabinet Diaries at the University of Bradford cover 1965-1971 and 1974-1976. In the 1945 General Election Barbara Castle was elected M.P. for Blackburn, a seat that she retained for 34 years. Following the Labour victory in 1964, Prime Minister Harold Wilson put Castle in charge of the newly-created Ministry of Overseas Development. “I decided on 26 January that I ought to start keeping a regular record of what was happening”, she said. Castle maintained this political diary throughout her periods in office. In 1974 Castle was made Secretary of State for Social Services, and in this post she introduced payment of child benefit to mothers and worked on the State Earnings Related Pensions Scheme. In 1979 she became a Member of the European Parliament and in 1990 she entered the House of Lords as Baroness Castle of Blackburn.

Alison Settle (1891-1980), fashion journalist and editor

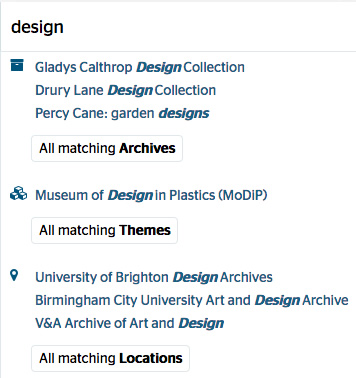

In a career spanning from the early 1920s to the early 1970s, Alison Settle worked as a fashion journalist, and Brighton Design Archive hold the Alison Settle Archive which includes professional papers dating from the mid-1930s. She was a tireless champion of the interests of women, as well as campaigning for good quality, affordable design through her relationships with designers and manufacturers. Settle sought to improve design standards in all areas of manufacture and production, and contributed to the work of both the Council for Art & Industry and the Council of Industrial Design. She remained one of the best known fashion journalists in the country.

Elise Edith Bowerman (1889-1973), lawyer and suffragette

Diaries, photographs and correspondence of Elsie Edith Bowerman are held at the Women’s Library. Bowerman followed her mother into the suffrage movement. They were both active members of the militant Women’s Social & Political Union. They were on the maiden voyage of the Titanic – both survived. She worked for Scottish Women’s Hospitals during the First World War, and she also worked for Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst during their campaign for ‘industrial peace’ in support of the war effort. In 1924 or 1925 she went on to set up the Women’s Guild of Empire with Flora Drummond, with the aim of promoting co-operation between employers and workers. She was admitted to the Bar in the early twenties and practised until 1938, when she joined the Women’s Voluntary Services. In 1947 Bowerman went to the United States to help set up the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women.

Tessa Boffin (1960-1993), writer, photographer and performance artist

The Tessa Boffin Archive at the University for the Creative Arts includes lesbian, gay, bisexual, transexual and other photography projects, including portrayal of AIDS, cross dressing and safe sex, as well as notes on television and radio productions of the 1980s portrayal on feminism and AIDS. Boffin was one of the leading lesbian artists in Great Britain during the AIDS Crisis, but her risqué performances were controversial, and frequently drew criticism, including from inside the LGBTQ community.

Gladys Aylward (1902-1970), missionary

Gladys May Aylward was an evangelical Christian missionary to China. She travelled to China in 1932 and in 1936 she became a Chinese citizen. In 1940, against the background of civil war between Nationalist government troops and the Communists, Japanese invasion, and the threat of bandits, she led a group of orphans on a perilous journey to Sian. Her story was told in the book The Small Woman, by Alan Burgess published in 1957, and made into the film The Inn of the Sixth Happiness starring Ingrid Bergman, in 1958. The Papers of Gladys Aylward, held at SOAS, provide a vivid portrait of Aylward, including her life in China, and the impact of World War Two.