We spend a great deal of time discussing each field in an archival description as part of the process of data aggregation and normalisation. But some fields raise more questions than others. I think overall we’ve probably spent the most time on the unique reference for each unit of description, which is so important when identifying and sorting descriptions and moving them around. Creator has also thrown up a number of challenges. Recently we’ve been thinking about ‘Genre/Form’. So, I thought I would post about it, as it reflects many of the types of issues that we think about as an aggregator.

On the Archives Hub, less than 1% of descriptions have genres or forms included. They can be in the core descriptive area and within the ‘control’ area as index terms – most are in the descriptive area. Quite a few of them are in our Online Resource descriptions of web resources that feature/display/explain archives, in particular they are in descriptions created for digitisation projects, where adding this information was part of the cataloguing process. In conclusion, it is clearly not common practice to add this information in archival descriptions.

When very few descriptions have a type of descriptive data – in this case genre/form – then the only thing you can really do is display it. If you provide a search or filter so that end users can find genre/form content, such as ‘photographs’ or ‘maps’ or ‘typescripts’ then you are encouraging them to narrow down their search to a tiny percentage of the descriptions – only those ones that have these terms included. Most users will assume that a search for ‘photographs’ will find all of the descriptions that include photos, when in reality it would find just a few percent. So, it is not a useful search; it is really a very misleading search. For this reason, in the imminent upgrade to the Archives Hub we are removing the links that we currently have on the genre/form entities, so that they do not create new searches.

Even displaying this data could be seen as misleading, because then the user might think that a description that doesn’t list ‘photographs’, for example, doesn’t have them, because other descriptions do list photographs. It is hard to convey to users that descriptions vary enormously. Even writing this now, I start to wonder whether it is worth us displaying the genre/form content at all when it may mislead in this way. Yet, it certainly can be useful for a researcher to know the types of content within a large collection.

Within the descriptions that do use this field, many are as you might expect, e.g. ‘photographs, leaflets, posters, letters, ephemera, books’. Others are more descriptive, e.g. ‘silver instruments in hard leather box’ or ‘Correspondence and other documents, architectural drawings, engineering contract drawings, and naval architecture publication’ or ‘Small ring-bound notepad’. Descriptive entries can convey more to a researcher, but they provide real challenges if you want to use the terms as links to allow users to search for other similar items. Also, a ‘small notepad’ might be ‘manuscript’ or ‘typescript’. If an end user searches for ‘typescript’ they would not find the small notepad. This is the problem of a lack of controlled vocabulary, and the problem of what ‘genre’ and ‘form’ really mean. The difficulty of separating them is clearly why they have ended up being bundled together.

We have not made an analysis of the use of controlled vocabulary, but it is clear that in general terms are not controlled. In our own EAD Editor, we provide links to the Getty Thesaurus of Graphic Materials and the Art and Architecture Thesaurus, but I am not sure how appropriate these are to describe all materials within an archive. Obviously an archive can include pretty much anything. If we just stuck to controlled vocabularies, we would probably omit some items. The Ivan Bunin collection from the University of Leeds is a great example of a description that lists a whole range of items – really useful to have, but difficult to see how this would work in a structured, controlled vocabulary world. In general, it seems to be common practice simply to list genre and form using local terms, which will differ between institutions, between cataloguers, and over time.

One of the issues I’ve mused upon is whether people are more likely to add a form such as ‘photographs’ and omit a form such as ‘typescript’, even if there are only a very few photographs, and a great deal of typescript material. Do the terms included really reflect the make-up of the collection? I suspect that cataloguers might think that end users are more interested in finding photographs or maps as genre types than finding typescript documents, and that may well be true. Also, it would be very difficult to list all the material types within a large collection, so only the main types, or clearly defined types are likely to be included.

As an aggregator, we have to understand and appreciate that each contributor has their own approach to cataloguing, and will use fields differently, or use them regularly, sometimes, or not at all. But also, I’m sure many of our contributors would say that across their descriptions there isn’t the level of consistency they would like, for various historical reasons. This is just multiplied when everything is aggregated. Aggregation allows for the power of global editing and enhancement, UK-wide interrogation and cross-searching, and serendipitous discovery. It is enormously powerful. It also creates a headache with how to harmonise everything in order to effectively do this.

The particular issue with genre/form came up because we are developing an Excel (spreadsheet) template for people to use if they prefer to catalogue in this way. We want to make sure the template is user friendly. We have included a column named ‘Genres/Forms’ and in the end we have simply made it a descriptive field without trying to structure or control the content. We will not try to add the content to our indexes, because of this complication of turning the text into structured data, and because we are not sure that it is really all that useful for the reasons outlined above.

Somewhat related to this, the new EAD standard, EAD3, has rather unhelpfully removed the sub-categories of ‘physical description‘, which are ‘extent’, ‘genreform’, ‘dimensions’ and ‘physfacet’ so that they all have to be bundled into just one field. Either that or you have to add a structured physical description which requires you to add a value from a list: carrier, material type, space occupied or other physdesc structured type (which asks you to then add the ‘other’ type). I can just imagine going back to all our contributors and asking them to add a type to all their physical description information! If we move to EAD3, we would remove the demarcation that tells us the information is about the genre/form or about the extent. This is potentially a deal breaker for us adopting EAD3, as taking away structure that is already there seems like madness. You could argue that simply having one free text field for physical description gets us off the hook with our attempts to work with the data (e.g. potentially using extent to provide a search to help convey the size of collections to users) – if it was completely unstructured then any attempt to analyse and present it differently would be impossible. However, just the process of putting these sub-fields together into one field would actually be extremely difficult due to the fact that different institutions have different patterns of data input. ISAD(G), the archival standard for description, doesn’t refer to form or genre at all, but recommends adding extent and medium, such as ’42 photographs’ or ‘330 files’, or else adding the overall storage space, such as 20 cubic metres. It doesn’t really go in for promoting structured data.

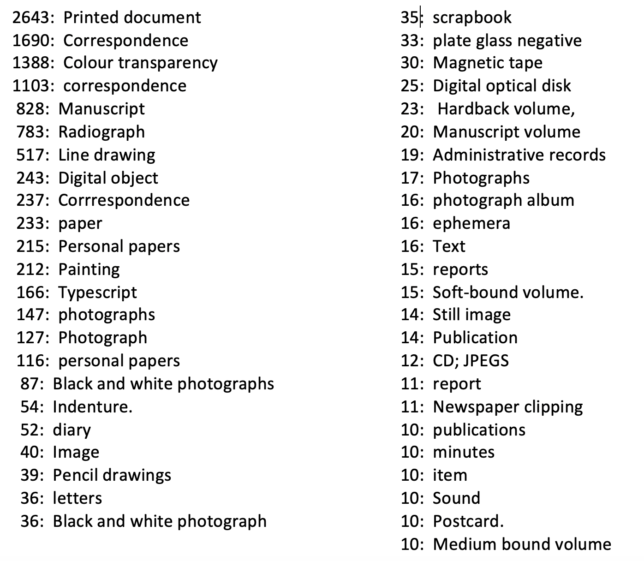

For those interested, here is a breakdown of the genre/form entries that have been used at least 10 times, just to give an idea of some common terms (though most entries include several types, so they will not appear in this list):

(Corrrespondence may be down to a rather extensive cut and paste error).

I’m not going to get into the thorny issue of what ‘genre’ is and what ‘form’ is. They were put together in EAD, whilst ISAD(G) doesn’t use these terms at all, but refers to ‘medium’. The distinction seems very blurred, and there are many archivists who will have more idea of what the definitions are than I do. I think it is very much open to interpretation for individual cataloguers – so we have entries like ‘small boxes’, ‘New Orleans-style jazz’ and ‘Museum administration’ and ‘social history’ as well as ‘personal papers’, ‘manuscripts’, ‘typescripts’ and ‘sound’.

In the end genre/form is a field that seems potentially very useful – the idea that researchers can search for maps, or prints, drawings or postcards, CDs or tape, is appealing, but in reality, we have never really prioritised this information in our catalogues. In our machine learning project, just kicking off, we may explore the possibility of interrogating descriptions to potentially add genre/form. It would be interesting to see how well this works. But I wouldn’t bet my house on it…or even my outhouse – the narrative style of most catalogues is likely to hinder any effective identification of material types.

We would love to hear from you if you utilise this field. Do you think it is useful? Do you try to add a comprehensive list of genres/forms? Do you think that researchers really want to search by material type?