Archives Hub feature for July 2018

Cambridgeshire Archives is privileged to hold the records of the Bedford Level Corporation. This significant archive, which includes records of Commissions of Sewers dating as far back as 1362, documents, arguably, the greatest land reclamation seen in the country’s history; the drainage of the Fens.

2018 marks the 200th anniversary of the commencement of work on one of the more controversial and problematic drainage projects undertaken; the Eau Brink Cut.

The Great East Swamp

Piecemeal attempts to drain the Fens (commonly referred to as the Great East Swamp and described by William Elstobb as the “deep and horrible fen”) enabling more land to be brought in to use for summer grazing began in medieval times. The swampy conditions were due to the constant tidal flooding of the Ouse, Nene and Welland which would overspill their natural banks causing widespread crop damage and creating an ideal environment for diseases such as malaria, known locally as Fen ague. Yet, this watery landscape also provided a livelihood peculiar to Fen dwellers who were unwilling to give up a traditional way of life trapping eels and fish and shooting wildfowl.

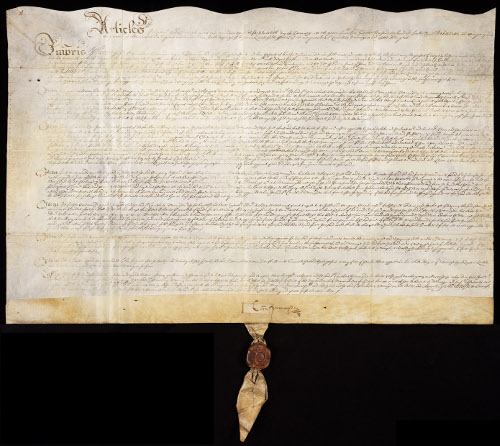

In 1630, despite local opposition, Francis 4th Earl of Bedford contracted with a number of landowners to drain, within six years, the area of the Southern Fen afterwards known as the Bedford Level. Sadly, the records of the work carried out over this period were stored in the Fen Office at the Inner Temples Chamber and largely destroyed during the Great Fire of London.

The Society of Adventurers and Cornelius Vermuyden

After the Civil War, Francis’ heir, Sir William Russell, 5th Earl of Bedford with some of the original ‘Adventurers’ and other interested parties, picked up the work again, this time with the aim of making the Bedford Level ‘winter ground’ capable of growing crops which could sustain cattle over the winter months. Under the Pretended Act of 1649 they came to be known as the Bedford Level Company or the Society of Adventurers. The Dutch engineer, Cornelius Vermuyden, who had been commissioned by Charles I in 1626 to drain Hatfield Chase in the Isle of Axholme in Lincolnshire, was appointed Director of Works.

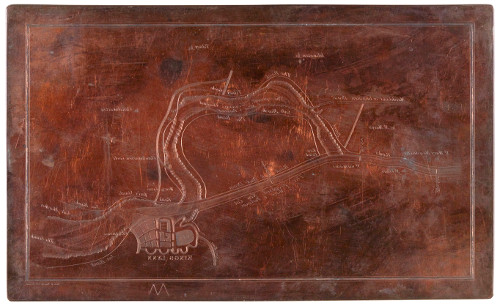

One of the many projects directed by Vermuyden was the construction of the Denver Sluice near Downham Market intended to ‘’force the tidal waters in a straight course up the Hundred Foot river, instead of allowing them to flow in their natural and more circuitous channel up the Ten Mile, or Ouse River.’ It was a heavily criticised undertaking, blamed, ironically, for causing flooding in the South Level of the Fens and the build-up of silt and sand downstream which proved injurious to navigation in the port of King’s Lynn. After a particularly high tide ‘blew up’ the sluice in 1713, merchants in the towns enjoying unobstructed navigation campaigned, unsuccessfully, against its reinstatement and it was reconstructed in 1748 by Charles Labelve.

The Eau Brink Cut

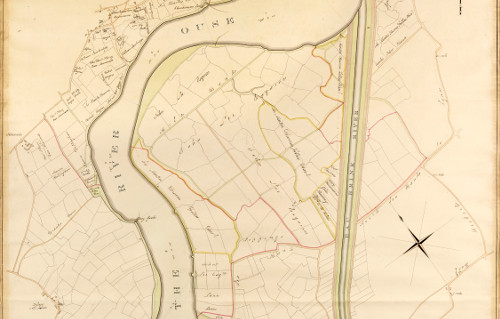

There is a wealth of material to be found in the Corporation’s archive, correspondence, reports, minutes and plans, for anyone wishing to trace the long and contentious struggle to come up with an effective and affordable means of improving the Ouse near King’s Lynn.

The eventual cost of obtaining the first Eau Brink Act, in 1795, was nearly £12,000. Further delays ensued so it is this year, 2018 which marks the 200th anniversary of the actual commencement of work on the Eau Brink Cut, a two and a half mile straight channel dug between St German’s Bridge and Lynn to provide an alternative route to the existing six mile bend in the Ouse.

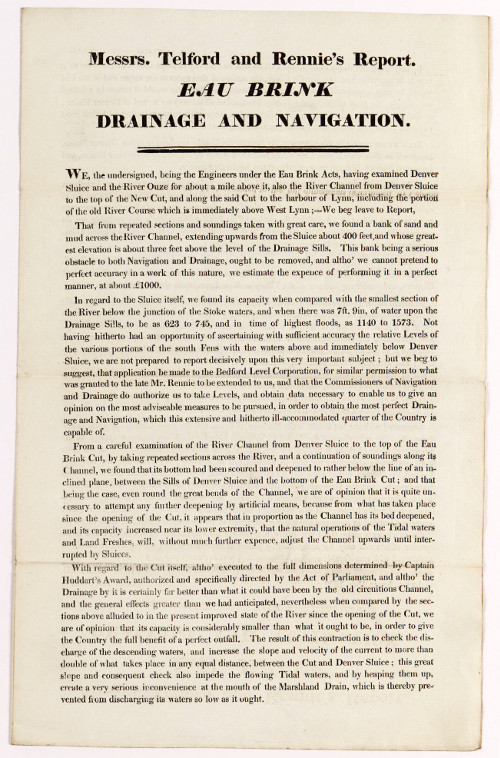

The construction of the Eau Brink Cut, under the aegis of engineers Thomas Telford and John Rennie, took nearly 4 years then, in April 1822, only a few months after the new cut was opened, they submitted a report recommending the channel be widened since a bank of sand and mud had already formed extending about 400 feet upwards from Denver Sluice.

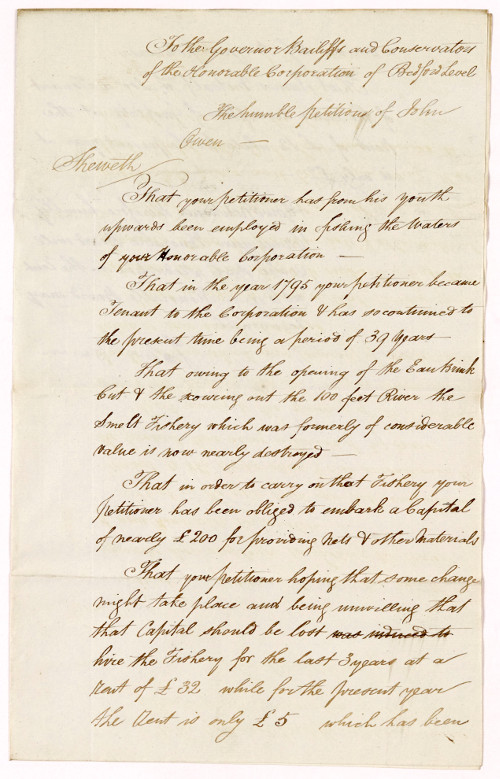

John Owen blamed the Eau Brink Cut for the destruction of his smelt fishery and having leased fishing rights in the Hundred Foot River for almost 40 years, petitioned the Corporation for a reduction in his rent so he could afford the £200 needed to invest in new nets and other equipment. Thousands of other memorials and petitions presented to the Corporation, all individually catalogued, now help document the personal impact of the monumental endeavour which was the draining of the Fens.

Sue Sampson

Public Services Archivist

Cambridgeshire Archives

Related

Records of the Bedford Level Corporation, 1630-1920

Browse all Cambridgeshire Archives collections on the Archives Hub.

All images copyright Cambridgeshire Archives and reproduced with the kind permission of the copyright holders.

In your Archives Hub feature for July 2018 you include a small error. You state ‘The construction of the Eau Brink Cut, under the aegis of engineers Thomas Telford and John Rennie, took nearly 4 years then, in April 1822, only a few months after the new cut was opened, they submitted a report …’ The Eau Brink Cut was designed by John Rennie senior on behalf of the drainage interests and its construction was supervised by him through the resident engineer, Thomas Townshend. Thomas Telford was what might now be called the checking engineer, appointed by the port of Kings Lynn to ensure that Rennie’s design did not harm the port. The cut was opened at the end of July 1821 and Rennie died on 4 October, so the 1822 report by Messrs Telford and Rennie that you illustrate was by Telford and John Rennie junior (later Sir John).