Archives Hub feature for August 2018

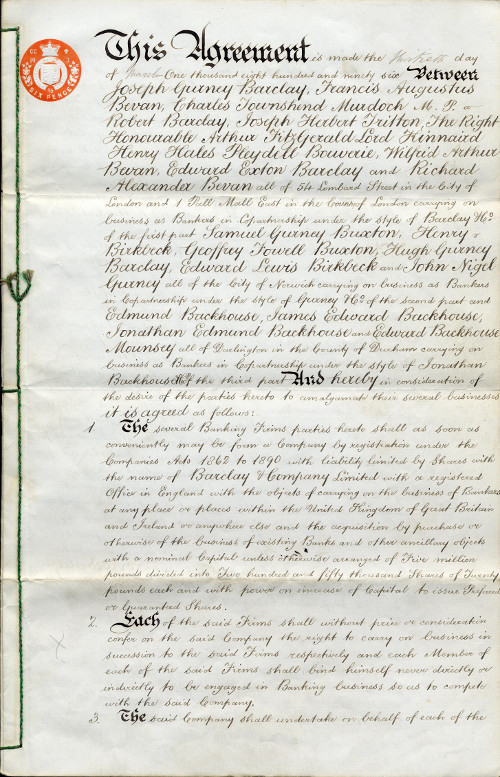

Barclays Group Archives has just posted a collection-level description for the records of Jonathan Backhouse & Co. of Darlington, one of the three principal partnerships that combined in 1896 to form the modern Barclays, which by the mid-20th century became the largest domestic clearing bank in Britain. The Hub entry for Backhouse bank complements descriptions previously posted for the other two principals in the merger, Barclays of Lombard Street and Gurneys of East Anglia.

The 1896 merger was described by The Economist at the time as ‘the largest of its kind that has yet taken place.’ It signalled the end of a long tradition of private banking, both in London and the provinces, the culmination of a process by which most of the private banks had converted themselves into, or been absorbed by, joint stock companies, during the previous 70 years.

Measured by total customer deposits, the three banks ranked as follows:

- Barclay, Bevan, Tritton & Co., Lombard Street (est. 1690) £8,589,530

- Gurney & Co., Norwich (est. 1775) £6,931,521

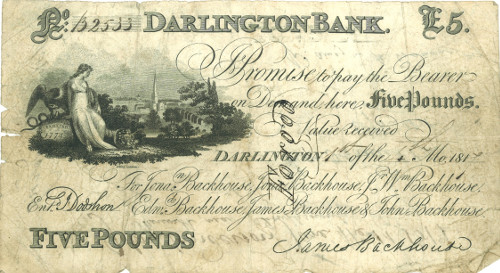

- Backhouse & Co., Darlington (est. 1774) £3,303,293

One of the distinctive features of all three was their origin in Quaker business enterprise. In both Gurneys and Backhouses the Quaker influence remained noticeable well into the 19th century, and another press comment on the 1896 merger referred to it as a combination of those ‘well-known Quaker firms’.

Although by 1896 few of the partners directly involved in the amalgamation were still practising Friends, they were content to claim a heritage that looked back to the Quakerly qualities of frugality, prudence and trustworthiness that had been so attractive to customers, and which had contributed to the remarkable growth of the banks in their early decades.

The reasons why so many Friends entered the business world in the first place are long acknowledged. Exclusion from mainstream professions and occupations led many to establish their own businesses, relying on their hard work and moral code to become trusted and respected figures within the mercantile community.

The historic core of the modern Barclays traces its origins from John Freame and Thomas Gould, two Quaker goldsmith bankers who in 1690 started a business in the heart of the City. The partnership was one of the most successful amongst the early bankers, pioneering the discounting of provincial bills of exchange. This success sprang at least in part from what has been described as ‘Quaker competitive advantage’.

They financed Quaker traders in the American colonies and helped to finance the Pennsylvania Land Company; they were actively involved in Quaker-dominated enterprises such as the London Lead Company and the Welsh Copper Company. The latter produced silver as a by-product, which Freame and Gould then sold to the Royal Mint. They were also the closest thing the Quakers had to an official banker, holding the Society of Friends’ central funds.

By the mid-1700s the partners were amassing fortunes which may have seemed at odds with the Quaker principles of simple and plain living; on the other hand, a Quaker who went bankrupt was liable to be disowned by the Society. While the fear of bankruptcy may have spurred the Barclays on to ever greater profitability, they still had not lost sight of other Quaker virtues.

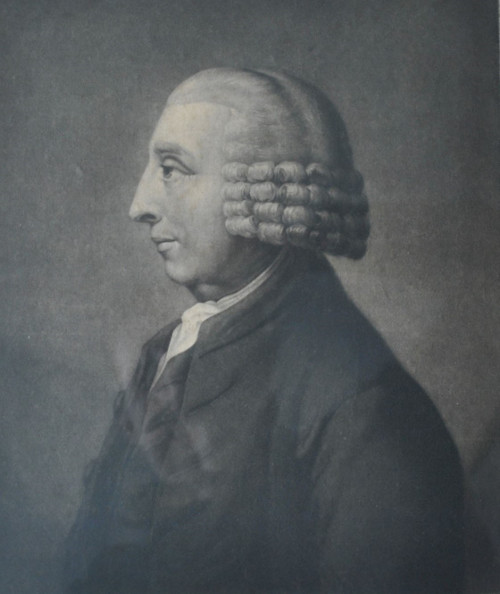

David Barclay the younger, who became a partner in the Bank in 1776, remained an active Friend throughout his career. A keen supporter of the emancipation campaigner William Wilberforce, he used his influence to persuade other Quakers to take a stronger stand for the abolition of slavery. Later, David Barclay found himself the owner of a plantation in Jamaica in settlement of a debt. His decision to free the slaves and transport them to Philadelphia cost him £3,000.

The country banks, too, sprang from the original business of their founders. In the case of both Backhouses and Gurneys this was textiles, though the former also had interests in shipping, coal mining and railways. One of the most eye-catching documents in the Backhouse archives is a signed and sealed agreement (currently on loan to Tyne & Wear Archives as part of the Great Exhibition of the North), between the subscribers for the construction of the pioneering Stockton-Darlington railway. The signatories comprise a roll-call of Quaker business families, including bankers who would, decades years later, come together in the modern Barclays: Backhouse, Pease, Barclay, Leatham, Gurney, and Birkbeck.

Jonathan Backhouse junior (1779-1842), grandson of the founder, argued in favour of a railway during a public meeting at Darlington town hall in 1818, stressing its commercial advantages over those of the conventional option, a canal. The first track was laid in May 1821, and the completed railway opened on 27th September 1825. Jonathan served as the company’s first treasurer until 1833. In 1811 he had cemented a significant Quaker banking alliance by marrying Hannah, daughter and co-heir of Joseph Gurney of Norwich: “of crucial importance…..this dynastic alliance in itself transformed the prospects for transport improvement, especially when the Backhouses allied themselves with the Quaker Pease family of Darlington in the raising of capital.” [M W Kirby, ‘Jonathan Backhouse’ in Dictionary of National Biography ] The Backhouses were also connected with the Barclays by marriage. After 1833 Jonathan left the business in the hands of his son Edmund, in order to devote himself full-time to the Quaker ministry.

Meanwhile the Gurneys of Norwich were establishing themselves as one of the leading commercial families in England, and came to be connected by marital, social and business ties with other Quaker banking families, including Barclay, Birkbeck, Buxton, Backhouse and Pease. Notable Gurneys in the bank’s history include Joseph John (1788-1847), religious writer, Quaker minister, anti-slavery campaigner and, like his sister Elizabeth Fry (nee Gurney), also active in prison reform; Hudson (1775-1864), scholar, member of parliament and philanthropist; and Samuel (1786-1856), philanthropist and partner in the Norwich bank for nearly forty years. Notable partners in the Norwich bank from the other families included Henry and William Birkbeck, Thomas Fowell Buxton, and Henry Ford Barclay. By 1838 the Gurneys were said to be ‘exercising an influence and a power inferior to that of no banking establishment in Great Britain – that of the Bank of England alone excepted.’

Like other successful Quakers, some of the Gurneys found it difficult to reconcile faith with wealth. Joseph John chose to become a ‘plain Friend,’ dedicating his life to his bank, his religion and good causes. In 1837 went on a three-year mission tour of the West Indies and America, giving away one third of his share of the bank’s profits for the duration. He was a renowned Quaker author, and his 1824 work, ‘Observations on the Religious Peculiarities of the Society of Friends’ was reprinted several times. His attitude is exemplified by his statement that “I suppose my leading outward object in life may be said to be the Bank. While I am a banker the Bank must be attended to. It is obviously the religious duty of a trustee to so large an amount to be diligent in watching his trust.

The history of the Quaker banks reveals all sorts of connections. For example, it’s no coincidence that the Backhouses used Barclay & Co. of Lombard Street for their London clearing agents in the 19th century. Both Backhouses and another Quaker country bank in the 1896 merger, Bassett & Harris of Leighton Buzzard, commissioned one of the renowned Gothic revival architects of Victorian England, Alfred Waterhouse, who was also from a Quaker family, to design new banking houses for them in the 1860s – the result being two remarkably similar buildings. Waterhouse also designed at least three country houses for the Backhouses in county Durham.

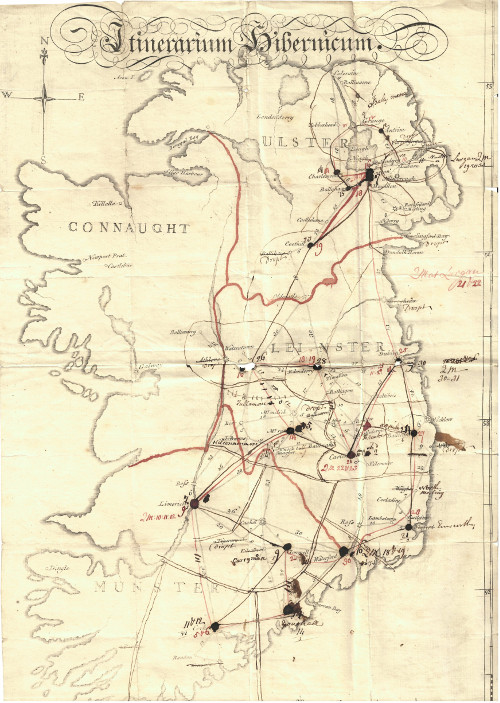

The Backhouse and Gurney archives each contain papers about the partners’ activities as Friends. For example, a Backhouse bundle from 1776-79 includes brief reports on the state of the various Meetings in Ireland visited by James Backhouse on his mission tour. Amongst the Gurney archives are papers concerning the old Friends’ burial ground at St. Stephen’s Green in Dublin, and a scarce contemporary print showing John Gurney, ‘the Weavers’ Friend’, with a printed testimonial following his speech before parliament on behalf of the Norwich weavers in 1720.

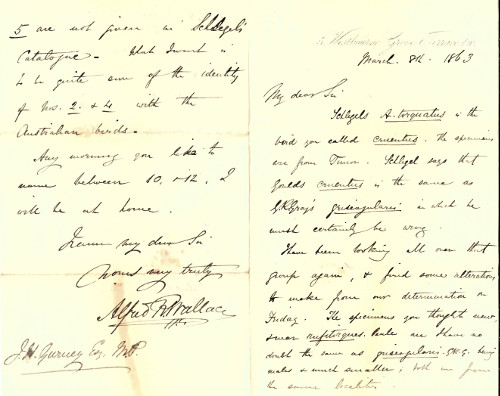

Although the bulk of the surviving records document the partners’ banking and business activities, there are also many items of wider interest in the collections listed on the Hub. Amongst the Gurney papers is a series of letters written during the 1850s-80s, between John Henry Gurney (bank partner, sometime Liberal M.P. and amateur ornithologist), his son of the same name, and various naturalists of their circle including Alfred Russel Wallace, mainly about birds and their classification. In the same archive is an eye-witness account of the devastating Lisbon earthquake of 1755 by Benjamin Farmer, member of a mercantile family connected with the Barclays.

At least three of the smaller banks in the 1896 merger also had Quaker founders or partners, and in due course their archives, too, will be described on the Hub: Sharples, Tuke, Lucas & Seebohm of Hitchin; Fordham, Gibson & Co. of Royston; and Bassett, Son & Harris of Leighton Buzzard.

Nicholas Webb

Archivist

Barclays Group Archives

Related

Jonathan Backhouse & Company, Darlington, 1615-1916

Browse all Barclays Group Archives collections on the Archives Hub.

Previous features by Barclays Group Archives

Barclaycard: 50 years of plastic money – the story from the Archives, June 2016

Barclays Group Archives, January 2014

All images copyright the Barclays Group and reproduced with the kind permission of the copyright holders.