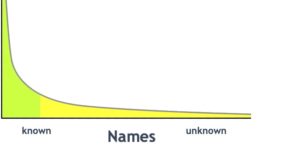

Having written several blogs setting out ideas and thoughts about challenges with names, this post sets out some of our plans going forwards in order to create name records for a national aggregator; something that can work at scale and in a sustainable way. The technical work is largely being undertaken by Knowledge Integration, our system suppliers, though working closely with the Archives Hub team.

Consider one repository – one Hub contributor. They have multiple archives described on the Archives Hub, and maybe hundreds or thousands of agents (people and organisations) included in those descriptions. All of this information will be put into a ‘management index‘. This will be done for all contributors. So, the management index will include all the content, from all levels, including all the names. A huge bucket of data to start us off.

A names authority source such as VIAF or any other names data that we would like to work with will not be treated any differently to Archives Hub data at this stage. In essence matching names is matching names, whatever the data source. So, matching Archives Hub names internally is the same as matching Archives Hub names to VIAF, or to Library Hub, for example. However, this ‘names authority’ data will not go into our big bucket of Archives Hub data, because, unless we create a match with a name on the Hub, the authority data is not relevant to us. Putting the whole of VIAF into our bucket of data would create something truly huge. It is only if we think that this external data source has a name that matches a person or organisation on the Hub that it becomes important. So data from external sources are stored in separate reference indexes (buckets) for the purposes of matching.

Tokenisation

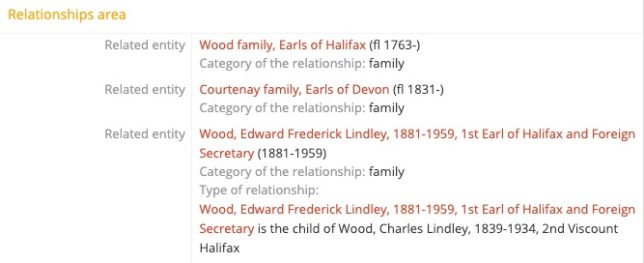

Knowledge Integration are employing a method known as tokenization, which allows us to group the data from the indexes into levels (It is quite technical and I’m not qualified to go into it in detail, so I only refer briefly to the basic principles here. Wikipedia has quite a good description of tokenization). With this process, we can establish levels that we believe will suit our purposes in terms of confidence. Level 1 might be for what we think is a guaranteed match, such as where an identifier matches. So, for example, Wikidata might have the VIAF identifier included, so that the VIAF and Wikidata name can be matched. In some cases, the Archives Hub data includes VIAF IDs, so then the Hub data can be matched to VIAF. We also hope to work with and create matches to Library Hub data, as they also have VIAF ID’s.

Level 2 might be a more configurable threshold based around the name. We might say that a match on name and date of birth, for example, is very likely an indication of a ‘same as’ relationship. We might say that ‘James T Kirk’ is the same person as ‘James Kirk’ if we have the same date of birth. This is where trial and error is inevitable, in order to test out degrees of confidence. Level 3 might bring in supporting information, such as biographical history or information about occupation or associated places. It is not useful by itself, but in conjunction with the name, it can add a degree of certainty.

We are also thinking about a Level 4 for approaches that are Archives Hub specific. For example, if the same name is provided by the same repository, could we say it is more likely to be the same person?

This tokenisation process is all about creating a configurable process for deduplication. Tokens are created only for the purposes of matching. Once we have our levels decided, we can create a deduplication index and run the matching algorithm to see what we get.

Approaches to indexing

For deduplication indexing, the first thing to do is to convert to lower case and remove all of the non-alpha characters. (NB: For non-latin scripts, there are challenges that we may not be able to tackle in this phase of the project).

The tokens within the record will be indexed in multiple ways within the deduplication index to facilitate matching. This includes indexing all words in order that they appear, and also individual word matches.

Then, particularly when considering using text such as biographies to help identify matches, we can use bigrams and trigrams. These essentially divide text into two and three words chunks. A search can then identify how many groups of two and three words have matched. Generally, this is a useful method of ascertaining whether documents are about the same thing. It may help us with identifying name matches based upon supporting information. This is very much an exploratory approach, and we don’t know if it will help substantially with this project, but certainly it will be worth trying out this approach, and also considering using it for future data analysis projects.

Character trigrams break down individual words into groups of three characters and may be useful for the actual names. This should be useful for a more fuzzy matching approach, and it help to deal with typos. It can also help with things like plurals, which is relevant for working with the supporting information.

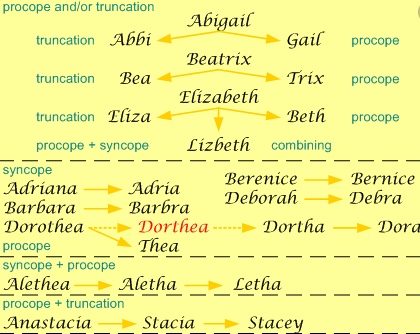

We are also going to explore hypocorisms. This means trying out matches for names such as Jim, Jimmy and James or Ned, Ed, Ted and Edward. A hypocorism is often defined as a pet name or term of endearment, but for us it is more about forename variations. Obviously Jim Jones is not necessarily the same person as James Jones, but there is a possibility of it, so it is useful to make that kind of match on name synonyms. It is often defined as a pet name or term of endearment.

From this indexing approach we can try things out and see what works. There is little doubt that it will require an iterative and flexible approach. We can’t afford to set up a whole process that proves ineffective so that we have to start again. We need an approach that is basically sound and allows for infinite adjustments. This is particularly vital because this is about creating a framework that will be successful on an on-going basis, for a national-scale service. That is an entirely different challenge to creating a successful outcome for a finite project where you are not expecting to implement the process on an on-going basis. Apart from anything else, a project with a defined timescale and outcome gives you more leeway to have a bit of human intervention and tweak things manually to get a good result.

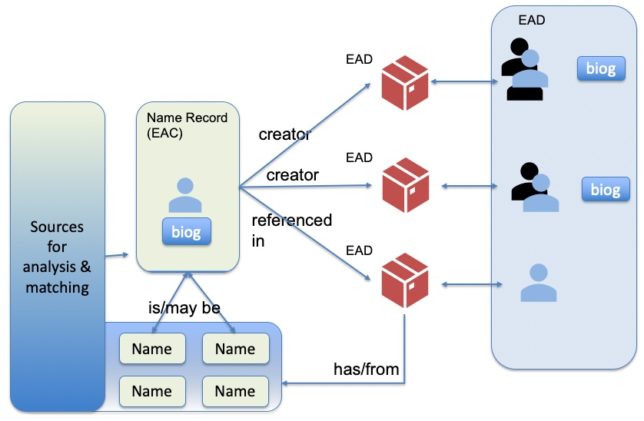

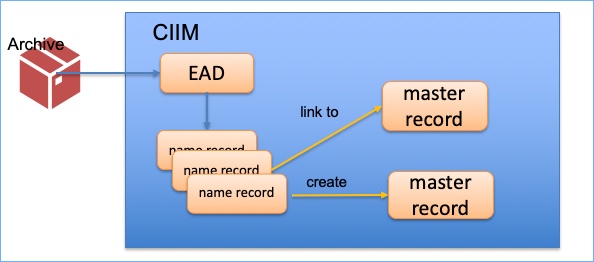

Group records

Using the tokenisers and matching methods we can try processing the data for matches. When records are matched with a degree of certainty, a group record is created in the deduplication index. It is allocated a group id and contains the ids of all of the linked records. This is used as the basis for the ‘master record’ creation.

Primary or master records

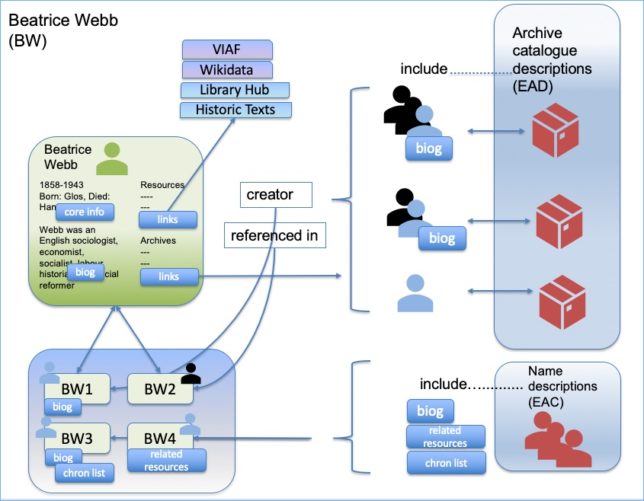

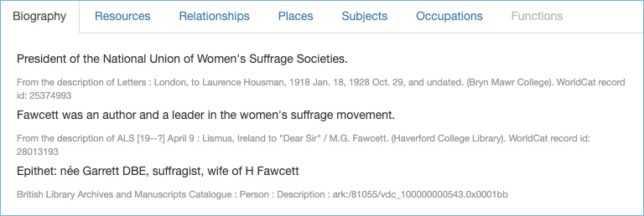

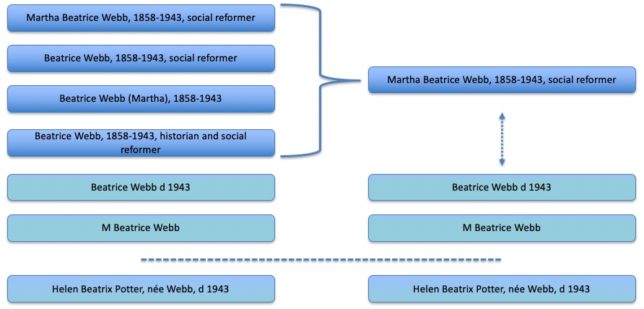

I have previously blogged some thoughts about the ‘master record’ idea. Our current proposal is that every Archives Hub name is a primary record, unless it is matched. So, if we start out with six variations of Martha Beatrice Webb, 1858-1943, then at that point they are all primary records and they would all display. If we match four of them, to a confidence threshold that we are happy with, then we have three primary records. One of the primary records covers four archives. We may be able to still link the other two instances of this name to the aggregated record, but we can assign a lower confidence threshold to this.

In the above example (which is made up, but reflects some of the variations for this particular name) four of the instances of the name have been matched, and so that creates a new primary record, with child records. Two of the instances have not been matched. We might link them in some way, hence the dotted line, or they might end up as entirely separate primary records. The instance of Beatrix Potter, nee Webb, has not been matched (these two individuals are often confused, especially as they have the same death date). If we set levels of confidence wrongly, this name could easily be matched to ‘Beatrice Webb’.

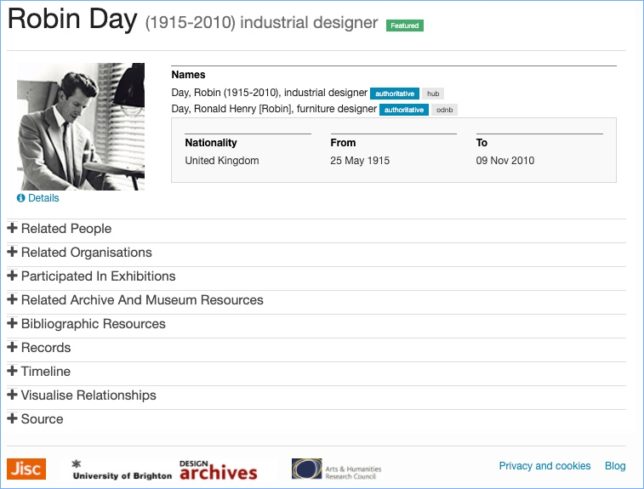

The reasoning behind this approach is that we aggregate where we can, but we have a model that works comfortably with the impossibility of matching all names. Ideally we provide end users with one name record for one person – a record that links to archive collections and other related resources. But we have to balance this against levels of confidence, and we have to be careful about creating false matches. Where we do create a match, the records that were previously primary records become ‘child records’ and they no longer display in the end user interface. This means we reduce the likelihood of the end user searching for ‘william churchill’ and getting 25 results. We aim for one result, linking to all relevant archives, but we may end up with two or three results for names that have many variations, which is still a vast improvement.

If we have several primary records for the same person (due to name variations) then it may be that new data we receive will help us create a match. This cannot be a static process; it has to be an effective ongoing workflow.