It is easy to focus on names that represent fairly well known people. But one of the challenges for archives is to work with little known people – names that represent someone who is referenced in a catalogue – maybe they are indexed because they are a correspondent for example – they appear in one of a series of letters – but there is no more information about them other than their name. They may be referenced in other sources, but we have little to go on in order to discover that, and often they won’t be represented – it may be that this is the only written source that includes them.

It is easy to focus on names that represent fairly well known people. But one of the challenges for archives is to work with little known people – names that represent someone who is referenced in a catalogue – maybe they are indexed because they are a correspondent for example – they appear in one of a series of letters – but there is no more information about them other than their name. They may be referenced in other sources, but we have little to go on in order to discover that, and often they won’t be represented – it may be that this is the only written source that includes them.

In a names service, we can add a name – let’s say ‘Louisa Jane Justamond’ – a name from https://archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/data/gb12-ms.add.8556 (‘The Garland continued’, a collection of poems addressed to her). We only have that one instance of that name. It is not in VIAF, it is not in Wikidata. There is an instance listed in ‘A genealogical and heraldic dictionary of the landed gentry of Great Britain’ (a precursor to Burke’s peerage). But unless we decide to use that an external source, write a name matching algorithm and decide, on levels of confidence, that it is indeed a match, that is not going to help us. We are left with a name attached to one archive collection and nothing else.

We can create a name record for Justamond, but if we display it on the Archives Hub it will simply show her name and a link back to the related description. It will be extremely minimal.

However, what we don’t know is whether new collections will be added to the Archives Hub, or new information added to Wikidata or another source that we use, such that this person becomes more identifiable. We simply don’t know what the value of a name might be. In the future, having a record of this person could prove to be immensely useful in making a connection.

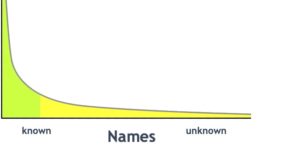

Archives have what you might call a long tail of names. It is something that characterises our holdings. It is something that sets us apart from libraries and museums, at least to a degree. Most names represented in library holdings (or names they represent in their catalogues and other finding aids) represent identifiable people.

In archives, we have collections that represent ordinary people, not published, not celebrated, not notorious, with no documented place in history. We also have collections that include people where it is hard to know whether an individual is more widely known, because the archive collection does not entirely identify them.

Either way, it leaves us with a question about how to deal with a name that has nothing else attached to it other than ‘this name is in this letter’.

Building an index of all names means that we have a store of data that can be used for further exploration. It could sit behind the scenes, but it can be used to try out tools, data manipulation and matching. In other words, the data is a separate thing from what you decide to display.

Having a name (maybe not knowing exactly who the name represents) and knowing that the name is in three different archives has value. We can say ‘in the absence of any other information, we assume these names represent the same person’, or we can simply present the information and not make any conclusions (although that begs the question of how you present it without encouraging assumptions). It is then up to researchers to explore further. We might find new data sources that help to clarify names. We might get new descriptions that help to do this.

Many archival descriptions include subjects and, to a lesser extent, places. If you have Stephen Merryweather in one, with an index term of botany, and S. Merryweather in another, with the same index term, then you could say it is more likely to be a match. There is a question of how you might then present that information. The use of algorithms raises the issue of how to convey levels of confidence. It feels as if we need to have a more sophisticated – and recognised – means of presenting levels of confidence.

This whole issue of confidence levels is more of a focus for archives, because of the anonymity I’ve talked about.

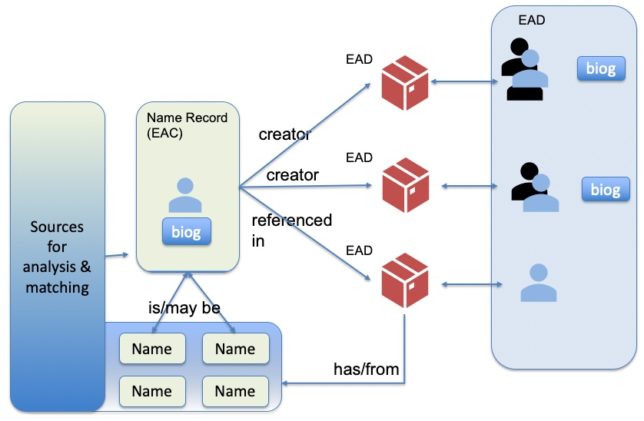

The ‘Name’ records shown above are the names within archival descriptions (EAD records on the Hub). These names can be pulled out from ‘origination’ (creator) and from ‘persname’ (usually in the controlaccess index section, but potentially elsewhere in the description). These names may represent ‘unknown’ people, the EAD may not even indicate whether they are personal or corporate or family names. They may not include dates, they may just be ‘Mary Fleming’ or ‘Mary Fleming fl 1717’. They may also be ‘unknown’, ‘[unknown]’, or even ‘unknown unknown’ (keeping the surname, forename structure!). They may be ‘Name of author (various)’ or ‘Various health authority bodies’ or ‘Possibly Miss M. Lindsay’. All these are examples from our data. They illustrate the conflict between human readable data – where ‘unknown’ is useful – and machine processable data – where semantics are important, and a name is ideally just a name.

If we create ‘Name’ entries for all of these then we have a store of data to work with, something I’ve mentioned before in my Names Project blogs. We can then find out how many ‘Mary Fleming’ entries there are, or how many ‘M Fleming’ entries. How we then choose to display that information to end users is a separate question. But with the advances in machine learning, it is becoming an increasingly pertinent question.

We have an opportunity with archival metadata, with the way that archives represent ‘ordinary life’. But it is a challenge Catalogues are still not really set up to identify entities (in a way that works for machine processing). We create what we refer to as ‘name authorities’ but we do not usually consider the importance of matching names outside of individual organisations. The Archives Hub has an opportunity to work on behalf of UK archives to try to draw out people and, in a sense, identify them, or at least, enable them to be more contextualised. But it will require a good deal of experimentation and expertise in working with disparate data. However, if we create a pool of names and provide an API, that would enable others to work with the data, and try different approaches. This is a big challenge, and it needs a concerted and collaborative approach.