Archives Hub feature for June 2015

As an international Christian Church and charity active in 126 countries, The Salvation Army is a well-known public presence. This year is its 150th anniversary and the occasion will be marked in the first week of July with the Boundless International Congress in London.

In its 150-year history, The Salvation Army has worked in many surprising ways and places. Since hiring its first professional archivist in 2007, The Salvation Army International Heritage Centre has steadily been opening up the organisation’s rich documentary heritage. Its recently catalogued archives provide a window into The Salvation Army’s diverse activities and the ways these have affected lives and shaped histories.

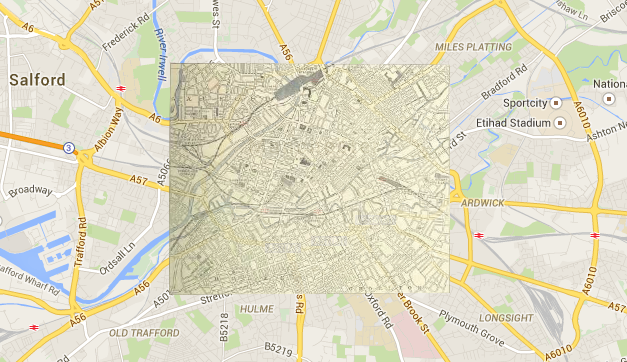

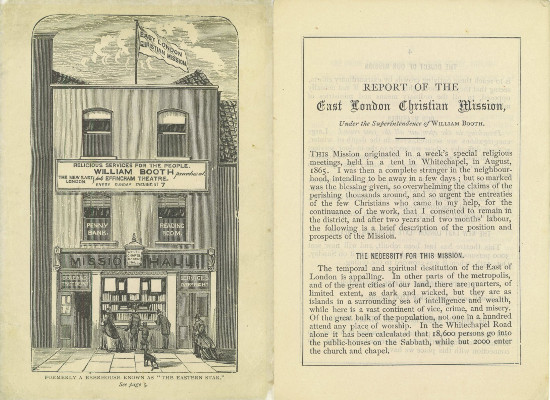

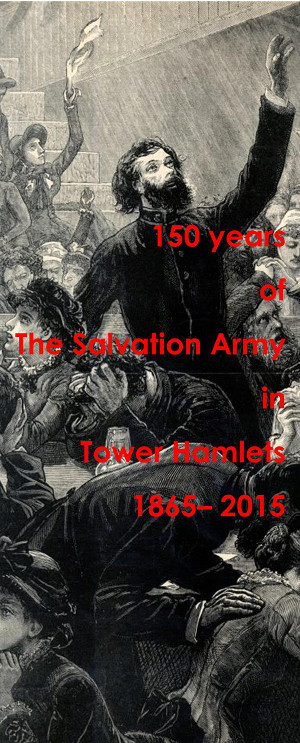

A series of tent meetings held in East London in August 1865 led to the development of the East London Christian Mission, which became known as The Salvation Army in 1878. The Mission spread quickly outwards from London throughout the UK, and within two years of becoming The Salvation Army it had begun expanding overseas. The organisation had always aimed to bring the gospel to the poor and vulnerable but in the mid-1880s, it started developing new ways of helping struggling and marginalised people materially as well as spiritually through social work.

The international and social dimensions of The Salvation Army’s work are particular strengths of the Heritage Centre’s collections and expertise. This feature highlights just two among many aspects of this work that can be researched in depth using the archives at the Heritage Centre. ‘Criminal Tribe’ settlements in India and early women’s rescue work are now easily accessible subjects thanks to catalogues and other finding aids that have been produced as a priority because of increasing interest from and collaborations with the research community.

India: Denotified Tribes

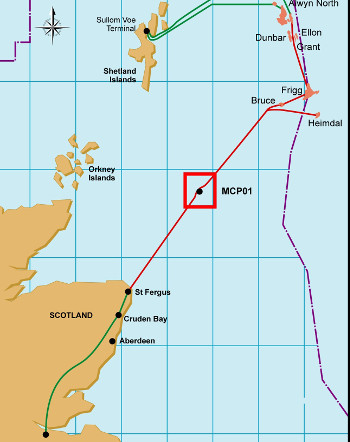

The Salvation Army describes India as its oldest mission field. Evangelical and social work started in Mumbai in 1882.

An important aspect of The Salvation Army’s work in India in the early to mid-twentieth century was its work with so-called ‘Criminal Tribes’. In 1871 the British Raj enacted the Criminal Tribes Act, which proposed that certain adivasi or ethnic, tribal communities in the Indian sub-continent were ‘habitually criminal’. As a consequence of the Act, Criminal Tribe settlements were established with the intention of altering the behaviour of these communities.

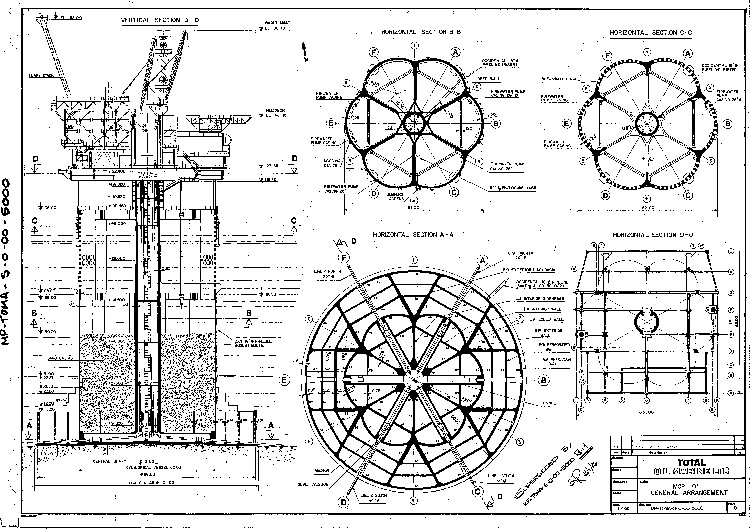

Anglo-Indian Salvation Army officer Frederick Booth-Tucker was a key exponent of developing agricultural and industrial settlements for Criminal Tribes. At first the British Raj did not agree to The Salvation Army’s attempts at rehabilitating Criminal Tribes but by 1908, after years of difficulties in managing settlements, it was willing to utilise missionaries. Within three years The Salvation Army was receiving government subsidies to run 22 settlements with approximately 10,000 residents and further settlements opened later.

The Salvation Army was still running five settlements when the Criminal Tribes Act was repealed by the newly independent Indian government in 1949. In 1952 Criminal Tribes were officially ‘de-notified’, but the impact of the former law is still being felt by communities today.

There has lately been considerable interest in the treatment of Criminal Tribes from a variety of researchers, including the production team of the documentary film Birth 1871: History, the State and the Arts of Denotified Tribes of India, so the Heritage Centre has prepared a guide to relevant records in its collections, now available on the Heritage Centre website. You can also read more about Salvation Army work in India and elsewhere on our blog.

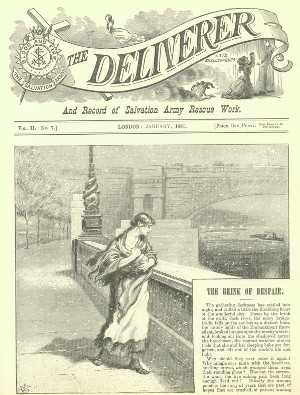

Women’s Rescue Work

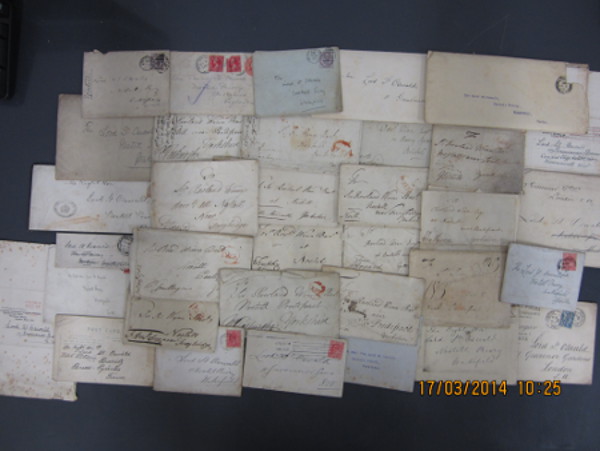

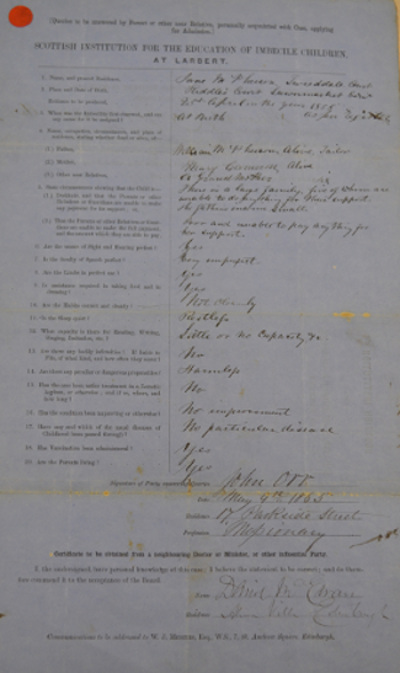

A number of highly successful student placements hosted by the Heritage Centre have led to an improved knowledge of The Salvation Army’s early rescue work with ‘fallen’ women, and better access to the relevant records. Each year, the Heritage Centre welcomes a student from UCL’s MA in Archives and Records Management and another from Birkbeck’s MA in Victorian Studies. In recent years, these students have focussed on the records of The Salvation Army’s Women’s Social Services resulting in a full catalogue of the collection and original research using the records.

The research of this year’s Victorian Studies student, Cathy David, has given new insight into the day-to-day running of The Salvation Army’s first rescue home for women, Hanbury Street Refuge, and the teething problems encountered in its earliest days. Cathy has also shown how different sets of our records can be read productively together to expose biases and subtext. Last year, Kate Taylor shed light on the extent to which the experiences of girls taken in by Hanbury Street Refuge influenced WT Stead’s journalistic exposé The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon, which led to the passing of the Criminal Law Amendment Act and the raising of the age of consent from 13 to 16 years of age. Their research was greatly aided by the catalogue produced by UCL student Arlinda Azaredo, which we hope to add to our existing descriptions on Archives Hub later in the year. It is already available on our online catalogue.

This year

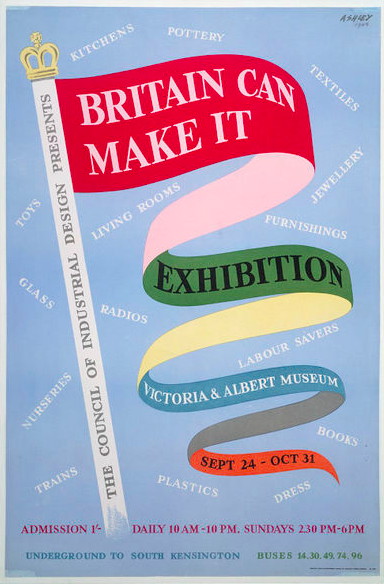

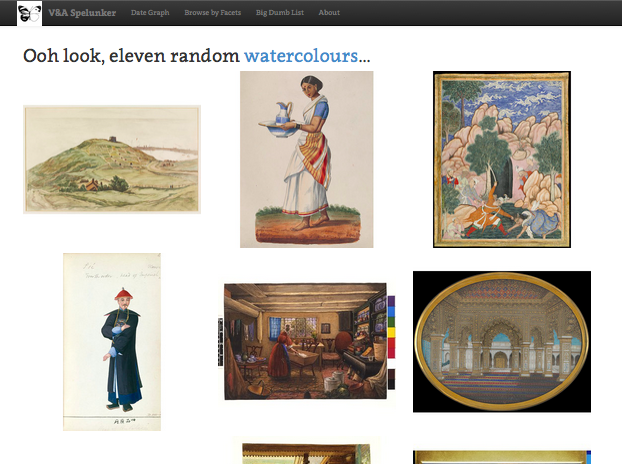

The 150th anniversary has afforded a wealth of further opportunities for the Heritage Centre to engage with communities, researchers and the media, improve its range of descriptive resources, and for staff to develop their expertise in a variety of ways. The Heritage Centre’s collections are expected to feature in a number of family history magazines in the coming months, and a two-week exhibition and programme of associated events in Tower Hamlets in early July is the outcome of a collaboration between the Heritage Centre, Stepney Salvation Army Corps and Tower Hamlets Council. The Heritage Centre also supplied images and loaned documents to the Geffrye Museum for the Homes of the Homeless exhibition, on now until 12 July. Subject guides and a blog have been added to our website, and more will appear throughout the year.

The Heritage Centre will be open longer during the Boundless Congress (29 June-6 July), and we look forward to welcoming many new visitors to our museum and archive reading room then. Full details of our extended opening hours are available on our website.

Ruth Macdonald

Archive Assistant, Salvation Army International Heritage Centre

Search for the Salvation Army descriptions on the Archives Hub

All images copyright the Salvation Army International Heritage Centre, and reproduced with the kind permission of the copyright holder.

Save