This is the first post outlining what the Archives Hub team have been up to over the past 18 months in creating a new system. We have worked with Knowledge Integration (K-Int) to create a new back end, using their CIIM software and Elastic Search, and we’ve worked with Gooii and Sero to create a new interface. We are also building a new EAD Editor for cataloguing. Underlying all this we have a new data workflow and we will be implementing this through a new administrative interface. This post summarises some of the building blocks – our overall approach, objectives and processes.

What did we want to achieve?

The Archives Hub started off as a pilot project and has been running continuously as a service aggregating UK archival descriptions since 1999 (officially launched in 2001). That’s a long time to build up experience, to try things out, to have successes and failures, and to learn from mistakes.

The new Hub aimed to learn lessons from the past and to build positively upon our experiences.

Our key goals were:

- sustainability

- extensibility

- reusability

Within these there is an awful I could unpack. But to keep it brief…

It was essential to come up with a system that could be maintained with the resources we had. In fact, we aimed to create a system that could be maintained to a basic level (essentially the data processing) with less effort than before. This included enabling contributors to administer their own data through access to a new interface, rather than having to go through the Hub team. Our more automated approach to basic processing would give us more resource to concentrate on added value, and this is essential in order to keep the service going, because a service has to develop to remain relevant and meet changing needs.

The system had to be ‘future proof’ to the extent that we could make it so. One way to achieve this is to have a system that can be altered and extended over time; to make sure it is reasonably modular so that elements can be changed and replaced.

Key for us was that we wanted to end up with a store of data that could potentially be used in other interfaces and services. This is a substantial leap from thinking in terms of just servicing your own interface. But it is essential in the global digital age, and when thinking about value and impact, to think beyond your own environment and think in terms of opportunities for increasing the profile and use of archives and of connecting data. There can be a tension between this kind of objective of openness and the need to clearly demonstrate the impact of the service, as you are pushing data beyond the bounds of your own scope and control, but it is essential for archives to be ‘out there’ in the digital environment, and we cannot shy away from the challenges that this raises.

In pursuing these goals, we needed to bring our contributors along with us. Our aims were going to have implications for them, so it was important to explain what we were doing and why.

Data Model for Sustainability

It is essential to create the right foundation. At the heart of what we do is the data (essentially meaning the archive descriptions, although future posts will introduce other types of data, namely repository descriptions and ‘name authorities’). Data comes in, is processed, is stored and accessed, and it flows out to other systems. It is the data that provides the value, and we know from experience that the data itself provides the biggest challenges.

The Archives Hub system that we originally created, working with the University of Liverpool and Cheshire software, allowed us to develop a successful aggregator, and we are proud of the many things we achieved. Aggregation was new, and, indeed, data standards were relatively new, and the aim was essentially to bring in data and provide access to it via our Archives Hub website. The system was not designed with a focus on a consistent workflow and sustainability was something of an unknown quantity, although the use of Encoded Archival Description (EAD) for our archive collection descriptions gave us a good basis in structured data. But in recent years the Hub started to become out of step with the digital environment.

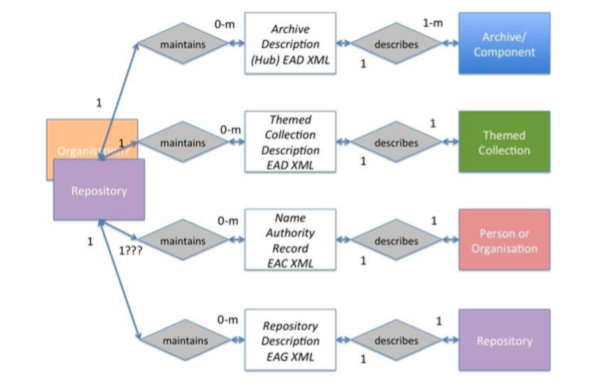

For the new Hub we wanted to think about a more flexible model. We wanted the potential to add new ‘entities’. These may be described as any real world thing, so they might include archive descriptions, people, organisations, places, subjects, languages, repositories and events. If you create a model that allows for representing different entities, you can start to think about different perspectives, different ways to access the data and to connect the data up. It gives the potential for many different contexts and narratives.

We didn’t have the time and resource to bring in all the entities that we might have wanted to include; but a model that is based upon entities and relationships leaves the door open to further development. We needed a system that was compatible with this way of thinking. In fact, we went live without the ‘People and Organisations’ entity that we have been working on, but we can implement it when we are ready because the system allows for this.

The company that we employed to build the system had to be able to meet the needs of this type of model. That made it likely that we would need a supplier who already had this type of system. We found that with Knowledge Integration, who understood our modelling and what we were trying to achieve, and who had undertaken similar work aggregating descriptions of museum content.

Data Standards

The Hub works with Encoded Archival Description, so descriptions have to be valid EAD, and they have to conform to ISAD(G) (which EAD does). Originally the Hub employed a data editor, so that all descriptions were manually checked. This has the advantage of supporting contributors in a very 1-2-1 way, and working on the content of descriptions as well as the standardisation (e.g. thinking about what it means to have a useful title as well as thinking about the markup and format) and it was probably essential when we set out. But this approach had two significant shortcomings – content was changed without liaising with the contributor, which creates version control issues, and manual checking inevitably led to a lack of consistency and non-repeatable processes. It was resource intensive and not rigorous enough.

In order to move away from this and towards machine based processing we embarked upon a long process, over several months, of discussing ‘Hub data requirements’. It sometimes led to brain-frying discussions, and required us to make difficult decisions about what we would make mandatory. We talked in depth about pretty much every element of a description; we talked about levels of importance – mandatory, recommended, desirable; we asked contributors their opinions; we looked at our data from so many different angles. It was one of the more difficult elements of the work. Two brief examples of this (I could list many more!):

Name of Creator

Name of creator is an ISAD(G) mandatory field. It is important for an understanding of the context of an archive. We started off by thinking it should be mandatory and most contributors agreed. But when we looked at our current data, hundreds of descriptions did not include a name of creator. We thought about whether we could make it mandatory for a ‘fonds’ (as opposed to an artificial collection), but there can be instances where the evidence points to a collection with a shared provenance, but the creator is not known. We looked at all the instances of ‘unknown’ ‘several’, ‘various’, etc within the name of creator field. They did not fulfill the requirement either – the name of a creator is not ‘unknown’. We couldn’t go back to contributors and ask them to provide a creator name for so many descriptions. We knew that it was a bad idea to make it mandatory, but then not enforce it (we had already got into problems with an inconsistent approach to our data guidelines). We had to have a clear position. For me personally it was hard to let go of creator as mandatory! It didn’t feel right. It meant that we couldn’t enforce it with new data coming in. But it was the practical decision because if you say ‘this is mandatory except for the descriptions that don’t have it’ then the whole idea of a consistent and rigorous approach starts to be problematic.

Access Conditions

This is not an ISAD(G) mandatory field – a good example of where the standard lags behind the reality. For an online service, providing information about access is essential. We know that researchers value this information. If they are considering travelling to a repository, they need to be aware that the materials they want are available. So, we made this mandatory, but that meant we had to deal with something like 500 collections that did not include this information. However, one of the advantages of this type of information is that it is feasible to provide standard ‘boiler plate’ text, and this is what we offered to our contributors. It may mean some slightly unsatisfactory ‘catch all’ conditions of access, but overall we improved and updated the access information in many descriptions, and we will ask for it as mandatory with future data ingest.

Normalizing the Data

Our rather ambitious goal was to improve the consistency of the data, by which I mean reducing variation, where appropriate, with things like date formats, name of repository, names of rules or source used for index terms, and also ensuring good practice with globally unique references.

To simplify somewhat, our old approach led us to deal with the variations in the data that we received in a somewhat ad hoc way, creating solutions to fix specific problems; solutions that were often implemented at the interface rather than within the back-end system. Over time this led to a somewhat messy level of complexity and a lack of coherence.

When you aggregate data from many sources, one of the most fundamental activities is to enable it to be brought together coherently for search and display so oftentimes you are carrying out some kind of processing to standardise in some way. This can be characterised as simple processing and complex processing:

1) If X then Y

2) If X then Y or Z depending on whether A is present, and whether B and C match or do not match and whether the contributor is E or F.

The first example is straightforward; the second can get very complicated.

If you make these decisions as you go along, then after so many years you can end up with a level of complexity that becomes rather like a mass of lengths of string that have been tangled up in the middle – you just about manage to ensure that the threads in and out are still showing (the data in at one end; the data presented through interface the researcher uses at the other) but the middle is impossible to untangle and becomes increasingly difficult to manage.

This is eventually going to create problems for three main reasons. Firstly, it becomes harder to introduce more clauses to fix various data issues without unforeseen impacts, secondly it is almost impossible to carry out repeatable processes, and thirdly (and really as a result of the other two), it becomes very difficult to provide the data as one reasonably coherent, interoperable set of data for the wider world.

We needed to go beyond the idea of the Archives Hub interface being the objective; we needed to open up the data, to ensure that contributors could get the maximum impact from providing the data to the Archives Hub. We needed to think of the Hub not as the end destination but as a means to enable many more (as yet maybe unknown) destinations. By doing this, we would also set things up for if and when we wanted to make significant changes to our own interface.

This is a game changer. It sounds like the right thing to do, but the problem is that it meant tackling the descriptions we already had on the Hub to introduce more consistency. Thousands of descriptions with hundreds of thousands of units created over time, in different systems, with different mindsets, different ‘standards’, different migration paths. This is a massive challenge, and it wasn’t possible for us to be too idealistic; we had to think about a practical approach to transforming descriptions and creating descriptions that makes them more re-usable and interoperable. Not perfect, but better.

Migrating the Data

Once we had our Hub requirements in place, we could start to think about the data we currently have, and how to make sure it met our requirements. We knew that we were going to implement ‘pipelines’ for incoming data (see below) within the new system, but that was not exactly the same process as migrating data from old world to new, as migration is a one-off process. We worked slowly and carefully through a spreadsheet, over the best part of a year, with a line for each contributor. We used XSLT transforms (essentially scripts to transform data). For each contributor we assessed the data and had to work out what sort of processing was needed. This was immensely time-consuming and sometimes involved complex logic and careful checking, as it is very easy with global edits to change one thing and find knock-on effects elsewhere that you don’t want.

The migration process was largely done through use of these scripts, but we had a substantial amount of manual editing to do, where automation simply couldn’t deal with the issues. For example:

- dates such as 1800/190, 1900-20-04, 8173/1878

- non-unique references, often the result of human error

- corporate names with surnames included

- personal names that were really family names

- missing titles, dates or languages

When working through manual edits, our aim was to liaise with the contributor, but in the end there was so much to do that we made decisions that we thought were sensible and reasonable. Being an archivist and having significant experience of cataloguing made me feel qualified to do this. With some contributors, we also knew that they were planning a re-submission of all their descriptions, so we just needed to get the current descriptions migrated temporarily, and a non-ideal edit might therefore be fine just for a short period of time. Even with this approach we ended have a very small number of descriptions that we could not migrate for the going live date because we needed more time to figure out how to get them up to the required standard.

Creating Pipelines

Our approach to data normalization for incoming descriptions was to create ‘pipelines’. More about this in another blog post, but essentially, we knew that we had to implement repeatable transformation processes. We had data from many different contributors, with many variations. We needed a set of pipelines so that we could work with data from each individual contributor appropriately.. The pipelines include things like:

- fix problems with web links (where the link has not been included, or the link text has not been included)

- remove empty tags

- add ISO language code

- take archon codes out of names of repositories

Of course, for many contributors these processes will be the same – there would be a default approach, but we sometimes will need to vary the pipelines as appropriate for individual contributors. For example:

- add access information where it is not present

- use the ‘alternative reference’ (created in Calm) as the main reference

We will be implementing these pipelines in our new world, through the administration interface that K-Int have built. We’re just starting on that particular journey!

Conclusion

We were ambitious, and whilst I think we’ve managed to fulfill many of the goals that we had, we did have to modify our data standards to ‘lower the bar’ as we went along. It is far better to set data standards at the outset as changing them part way through usually has ramifications, but it is difficult to do this when you have not yet worked through all the data. In hindsight, maybe we should have interrogated the data we have much more to begin with, to really see the full extent of the variations and missing data…but maybe that would have put us off ever starting the project!

The data is key. If you are aggregating from many different sources, and you are dealing with multi-level descriptions that may be revised every month, every year, or over many years, then the data is the biggest challenge, not the technical set-up. It was essential to think about the data and the workflow first and foremost.

It was important to think about what the contributors can do – what is realistic for them. The Archives Hub contributors clearly see the benefits of contributing and are prepared to put what resources they can into it, but their resources are limited. You can’t set the bar too high, but you can nudge it up in certain ways if you give good reasons for doing so.

It is really useful to have a model that conveys the fundamentals of your data organisation. We didn’t apply the model to environment; we created the environment from the model. A model that can be extended over time helps to make sure the service remains relevant and meets new requirements.