Archives Hub feature for August 2016

Browse collections on the Archives Hub relating to Tibet.

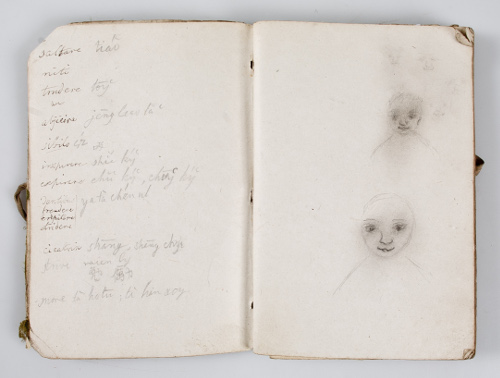

In December 1811, Thomas Manning entered Lhasa, Tibet, with his Chinese servant. On the 17th, December, Manning was allowed into the presence of the 9th Dalai Lama – the six-year-old Lungtok Gyatso. Manning drew sketches of the child and wrote:

“[He] had the simple and unaffected manners of a well-educated princely child. His face was, I thought, poetically affecting and beautiful. He was of a gay and cheerful disposition… I was extremely affected… I could have wept with the strangeness of sensation.”

No other Englishman would enter Lhasa until the Younghusband expedition to Tibet at the beginning of the twentieth century. Many might think that Manning’s visit would mark a pinnacle in his career, but for Thomas Manning reaching Lhasa, and not being able to proceed further, was a source of great disappointment. Manning’s passion was China and the sole reason he travelled to Lhasa was in an attempt to reach Peking and other parts of inland China.

When Manning first became interested in China is uncertain. Indeed much about Manning, until this point, has been little known. His trip to Lhasa was published posthumously in 1876 in Narratives of the Mission of George Bogle to Tibet and of the Journey of Thomas Manning to Lhasa, edited by Clements R. Markham. It was also known that Manning was an influential friend of the essayist, Charles Lamb. Their letters are in the public domain, held in archives in the USA.

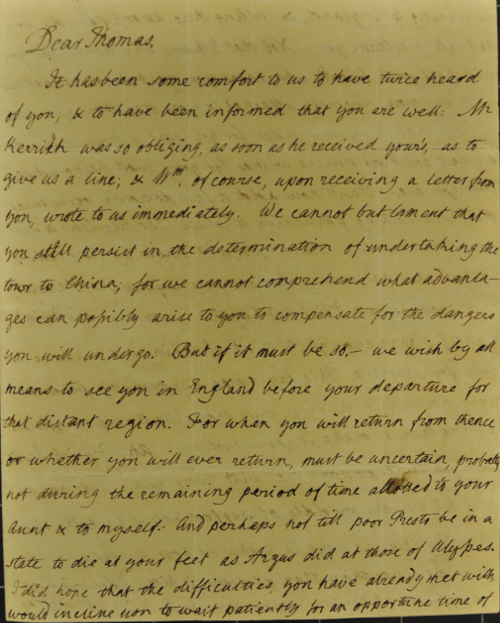

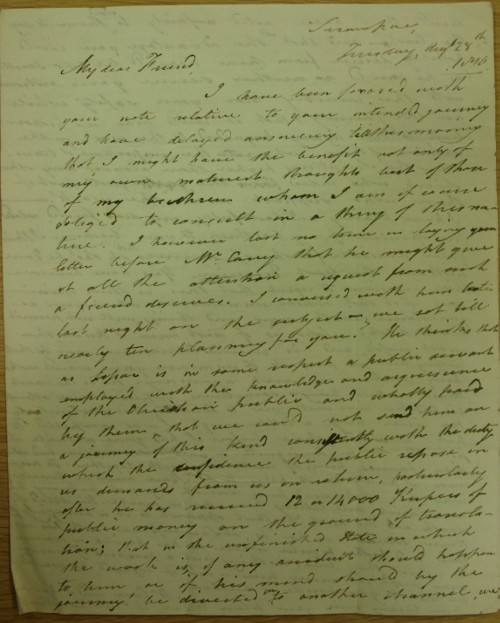

In 2014, a cache of Manning’s papers were discovered which were acquired, in 2015, by the Royal Asiatic Society with funding from The National Heritage Memorial Fund, Arts Council England / Victoria and Albert Museum Purchase Grant Fund, Friends of National Libraries, and private donations. The Thomas Manning Papers, which include correspondence with his family and friends, notebooks, an early manuscript account of the journey to Lhasa, and official passports and documents, are now catalogued on the Archives Hub.

Thomas Manning was born in 1772, the second son of William Manning, rector of Diss. He was educated locally in Norfolk and went to Cambridge in 1790 to study mathematics at Gonville and Caius College. He was an astute mathematician but did not graduate because he wouldn’t subscribe to Church of England doctrines, necessary for matriculation at that time. However, he stayed on in Cambridge preparing students for mathematical examinations and writing textbooks. For Manning mathematics was a lifelong passion: some of the workings within the mathematical archives date from the years shortly before he died.

At Cambridge, Manning also developed his obsession to learn about China and the Chinese. Manning hoped to discover: “a moral view of China; its manners; the actual degree of happiness the people enjoy; their sentiments and opinions, so far as they influence life; their literature; their history…”

At this time, in England, interest in China was negligible. He therefore travelled to France to learn more, departing from Dover in January 1802. The archive contains the George III passport for his passage. Manning’s correspondence includes details of meeting Thomas Paine and Maria Cosway; of being inspired by Napoleon; of a hushed-up assassination attempt; and of learning from Joseph Hagar, “the Conservator of the Oriental manuscripts…The Dr and I shall probably become intimate, as I am learning the Chinese tongue, & so curious a language is a greater bond of union among men than even Free-masonry”.

Manning’s stay became extended by the outbreak of conflict between England and France. However Manning was well treated, being able to continue his studies in Paris or reside with the de Serrant family at their chateau in the Loire.

After consistent appeals to Napoleon, explaining his desire to travel to China, Manning was allowed to return to England. He then studied for 6 months at Westminster Hospital, gaining medical knowledge he hoped to be of benefit during his travels. He considered journeying overland to China via Russia but decided instead to apply, via Sir Joseph Banks, to the East India Company to sail on one of their vessels to Canton.

The Company agreed. Manning sailed from Portsmouth, aboard the Thames, in May 1806, reaching Canton in January 1807. Here he lived in the Company factory, set about learning the Chinese language, and undertook medical and translation work.

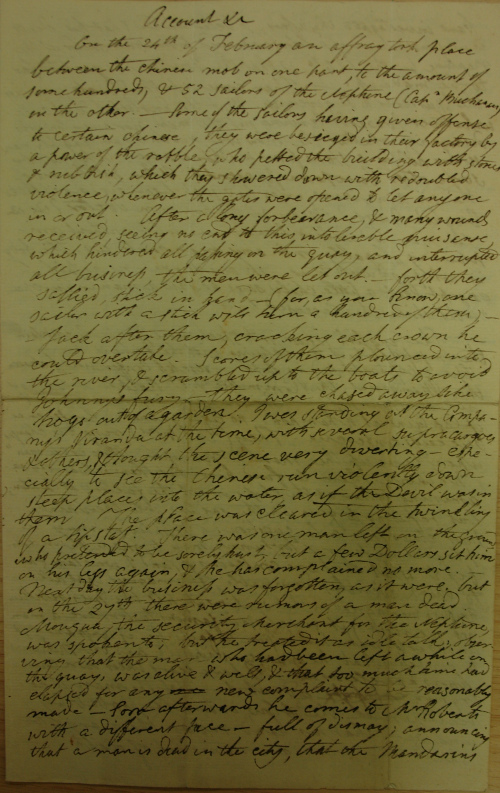

Manning’s letters have details of life in Canton including a riot that led to the death of a Chinese man and precipitated the diplomatic incident over the crew of the Neptune. Manning appears to have observed the events first-hand. He wrote an eyewitness account, as well as comments on the ensuing trial: “…The court is opened in a very striking manner – 1st Solemn & lofty words by a herald – then a lengthened resounding cry of hou… then a sonorous & aweful clangor of Gongs … Each man asked to say that he is guilty… Each man refuses… To hear those ragamuffins speak they were all as gentle as Lambs that day…”

He desperately wanted to get beyond Canton. In late 1807 Manning offered his services as a physician and astronomer to the Emperor, but wasn’t accepted .Then in early 1808 Manning tried to enter China through Vietnam. This project failed also. Despite these frustrations he continued to make progress with Chinese: “I have discovered the nature of the tones. I can speak. I can read. I am sure of being able to pursue the study of Chinese books in Europe.”

In 1810 Manning decided on a new plan – to attempt to enter China via Tibet. He travelled to Bengal and arrived in Calcutta in early 1810. He wrote to his father of dealings with European “missionaries in Calcutta who claim to know something of the Chinese language but they have it wrong… their translations of Confucius are a map of mistakes”. There are eight letters from Joshua Marshman, Serampore missionary, in the archive thanking Manning for his help with Chinese translation. In Bengal Manning waited for permission to travel to China via Bhutan and Tibet. Permission came for the first stage of the journey, and Manning kept going until he reached Lhasa.

But that was the end of his trip. From Lhasa he was sent back, unsuccessful in his bid to discover more about inland China. He returned to Canton to continue studying until another opportunity arose to see more of China with the mission of the Amherst Embassy, which departed for Peking in 1816.

Manning was enrolled with the Embassy as an interpreter. Amherst objected to Manning’s beard and Chinese dress but George Staunton intervened to secure him a place. The presence of Manning, Staunton and Robert Morrison as the interpreters gives us a cameo of those interested in Chinese at that time – Staunton the East India man/diplomat, Morrison the missionary and Manning the independent scholar.

The Embassy ended in failure due to perceived slights to the Emperor by Amherst. The Embassy remained in Peking for just a few hours. Possibly this was the final straw for Manning – he chose to return to England with the Embassy – a passage that involved shipwreck, and a stopover at St Helena to speak with the exiled Napoleon. The archive contains notes from Manning’s conversations with Napoleon and Hudson Lowe, Governor of St. Helena.

Back in England, Manning was still interested in China and Chinese. He had brought with him two Chinese men which he hoped the East India Company would employ to help prepare Company men for service in China. But Manning found they were not interested in employing or in helping defray the costs of bringing the men to England.

Manning continued his Chinese studies and revived old friendships with the likes of Lamb and George Leman Tuthill, an eminent physician. He became honorary Chinese librarian to the Royal Asiatic Society in 1824, and was active in helping Stanislas Julien, the French sinologist, find Chinese material. He was still keen to learn new things and lived in Italy between 1827 and 1829 to improve his spoken Italian. He settled near Dartford, Kent, where he had the finest Chinese library in Europe. This library was bequeathed to the Royal Asiatic Society and is now part of the Brotherton Library’s Chinese Collection (Leeds University), having been donated by the Society in 1963.

Manning did not publish his Chinese discoveries and therefore has often been overlooked amongst those studying early Sinology and Orientalism. The Royal Asiatic Society hope that the acquisition and cataloguing of this archive, might aid towards a greater understanding of these topics, and of the life of Thomas Manning: not only the first Englishman to reach Lhasa, but also, possibly, the first independent English scholar of China and the Chinese, a gifted mathematician, a lover of riddles and a loyal friend.

Nancy Charley

Archivist

Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland

Related:

Papers of Thomas Manning, Chinese Scholar, First English visitor to Lhasa, Tibet on the Archives Hub: https://archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/data/gb891-tm

Browse the Royal Asiatic Society’s Collections on the Archives Hub.

All images copyright the Royal Asiatic Society and reproduced with the kind permission of the copyright holder.

Save