There have been some threads on archives-nra recently about adding names to archival catalogues, so I thought it might be good to blog about it, reflecting the Archives Hub’s experience and knowledge on this topic after 20 years of working with aggregated data, and three Linked Data projects. We are also about to embark upon a ‘Names Project’ with the intention, in the first phase, of laying the groundwork for creating something that is interoperable and sustainable. The idea is to develop the Archives Hub so that we can include name records, with the ability to ingest and process them automatically and at scale, which is a big challenge.

What rules or guides should you follow for creating a name?

To start with, one of the interesting things about this topic is that the development of persistent unique identifiers (PIDs) should actually make consistency with name form and pattern less of an issue. (I say that advisedly, as someone who has always promoted consistency, following rules, and using care with constructing names). Of course, this only works if PIDs are assigned to names. To take an example – here is a list of names for one person, the Victorian social reformer Beatrice Webb:

Webb Martha Beatrice 1858-1943 Social Reformer

Webb Beatrice 1858-1943 social reformer

Webb, Martha Beatrice. ( 1858-1943) nee Potter Social Reformer

Webb Martha Beatrice 1858-1943 nee Potter, social reformer and historian

WEBB, Beatrice, 1858-1943

Webb, Martha Beatrice

Webb, M.B., 1858-1943

Webb, Martha, b. 1858, wife of Sydney Webb

Potter, Martha Beatrice, 1858-1943

Martha Beatrice Potter, 1858-1943

If all instances of this name were accompanied by recognised and agreed identifiers, then job done, we know they all represent the same person, whatever the form of the name.

It is important to state that ‘knowing who this is’ applies to both humans and machines. Humans will probably gather that these all represent the same person; the question is whether they can all be matched programmatically.

Still, we’ve a long way to go before universal PID harmony, and we’ve also got the problem of which identifiers to use. So, we’re back to rules for the construction of a name, which, of course, have many advantages besides disambiguation.

The archives community in the UK is likely to turn to ISAAR(CPF) and the NCA Rules. Sometimes the question is asked about which one to use, but in truth they are complimentary and so a choice is not needed.

ISAAR(CPF) is about a full name authority, as it is generally understood within the archive community – essentially a biographical record, documenting the nature, context and activities of the entity, preferably providing relationships to other people and organisations. The idea is to provide context about the records’ creation and use, which helps the user to understand and interpret the archive collection, something that archivists see as an essential activity.

The term ‘name authority’ can simply apply to the name itself as well as to a full record about an entity. This is typically the case in the Library world, but even in NCA Rules (which I’ll come on to), the term is defined as “the recognised, authorised or prescribed form of a name”. This difference in definition can sometimes cause confusion.

ISAAR(CPF) states that it “is intended to be used in conjunction with existing national standards or as the basis for the development of national standards”, and “rules and conventions for standardizing access points may be developed nationally”. ISAAR(CPF) is about a whole lot more than the name; it is about describing the entity and the relationships it has with with other entities. For the authorised form of the name, you are prompted to use national conventions or other guidance. The standard also allows for other forms of the name, but essentially the way the name is constructed and the dividers used are not prescribed. ISAAR(CPF) does also allow for an authority record identifier – which comes back to the PIDs mentioned above, but it does not prescribe the identifier used.

So, that leaves NCA Rules, which are about the construction of names. I’m just going to focus on personal names for this blog post.

As far as I’m concerned, there is loads of good and useful stuff in these Rules. Going through the rules really brings home just how complicated names can be. Everything from medieval surnames to greek names to names with no identifiable surname, pre-titles and epithets is addressed. I’ve particularly found the rules on royal names and papal names useful myself. If you want to know how to deal with William of Malmesbury or the Duchess of Marlborough it’s great.

The NCA Rules were created in 1997, which is an age away in terms of the modern digital and online age, and yet so much of what they say is still useful, because in the end we haven’t changed our names. However, in the digital age we continue to change how the names that we construct are stored, transferred, displayed and used. I think that this means that parts of the NCA Rules are no longer so helpful.

Hyphenated and compound surnames

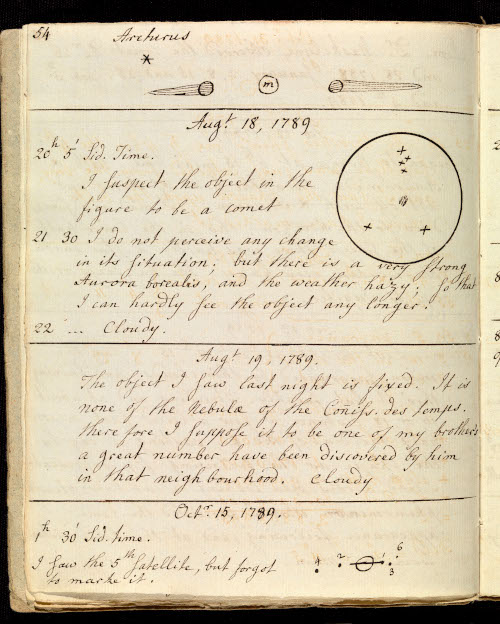

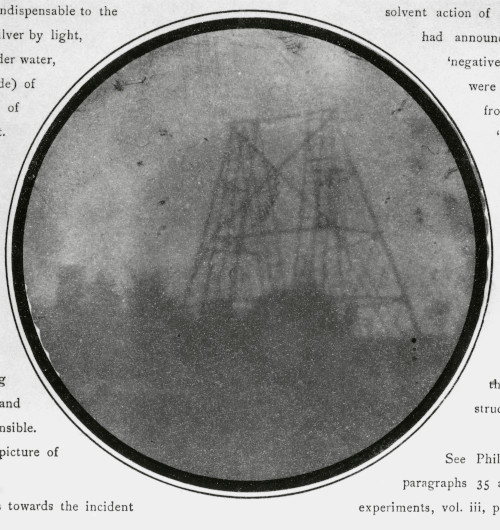

This is a particular problem as far as I’m concerned. If you want to enter the name of William Henry Fox Talbot, the Rules propose using Talbot | William Henry | Fox. You can cross-reference to ‘Fox Talbot’. However, in modern databases and formats like XML, you are in danger of ending up with:

Surname: Talbot

Forenames: William Henry Fox

In terms of archival catalogues, this may not be so bad. If there is a search by name, it usually searches across the whole name, so ‘Fox Talbot’ as a search is likely to bring back the record. The display of the name may be Talbot, William Henry Fox, but a researcher is likely to understand who that is from the context of the description. Humans are generally good at interpretation through context.

However, for those of us pushing forward with the principles of joined-up data and moving towards the ideal of Linked Data (even if we don’t fully get there), this structure is a problem. In the Archives Hub we could end up with:

<persname>

<surname>Talbot</surname>

<forename>William Henry Fox</forename>

<dates>1800-1877</dates>

</persname>

Clearly, this is not correct, and it becomes harder to connect it with other instances of the name. As stated above, if we all used agreed PIDs it would not be such a problem, e.g.

<persname authfilenumber=”https://viaf.org/viaf/54325833″ source=”viaf”>

<surname >Talbot</surname>

<forename>William Henry Fox</forename>

<dates>1800-1877</dates>

</persname>

But applying these PIDs (even if we do manage to agree what they are) to all our catalogues retrospectively….well, that’s a bit of a job. And it would require the kind of analysis of names that much prefers semantically well-structured names, so kind of a catch 22.

That leaves the recommended route of stating that the ‘entry element’ for the surname is, well, the surname. Hyphenated surnames are the same. NCA Rules plumps for “Lewis” as the entry element for Cecil Day-Lewis. I would argue for it being “Day-Lewis”.

I think there is a similar issue with prefixes such as ‘Du’ and ‘Van’. Putting Daphne Du Maurier under ‘Maurier’ is not right…

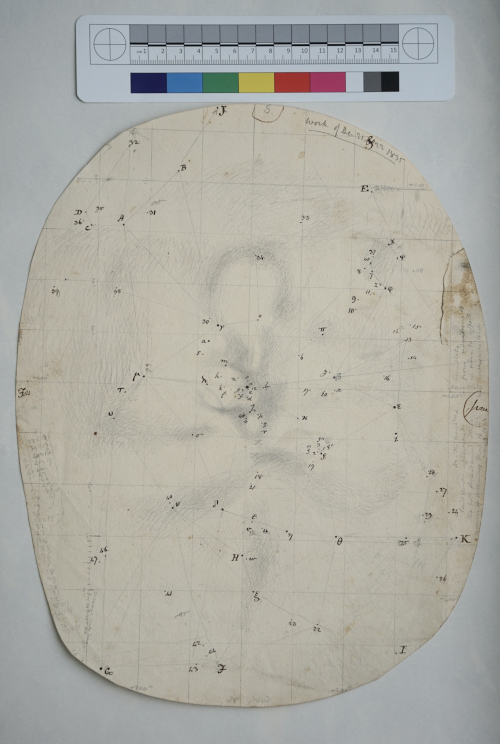

Being part of the wider world

One reason ‘Maurier, Daphne Du’ is not right is clear when you look at http://viaf.org/viaf/24600806. This is the Virtual International Authority File entry for Daphne Du Maurier. Only the Lebanese National Library has gone for ‘Maurier, Daphne Du’. Of course, the name has still been matched with the others, so no harm done in a sense, at least on VIAF. But it doesn’t really help matters to be out of sync with everyone else where names are concerned.

VIAF is the Virtual International Authority File, and it is a good place to start when thinking about persistent unique identifiers and the benefits of data join-up. It is not perfect, but what it does is to push things towards interlinked data and to enable the kind of connectivity that Linked Data is after. Other authority files are available (which is part of the problem), but VIAF is widely used, it sources from many countries, and it is fairly comprehensive.

Going back to Beatrice Webb. She is also in VIAF: http://viaf.org/viaf/86607236. Just as with Daphne Du Maurier, you can see how all the variations in the name have been brought together. But there is more value to VIAF than this. It also brings in other data. As well as related names, related works and publishers it includes links to Wikipedia in a whole range of languages. It also records the ISNI (International Standard Name Identifier) and WorldCat Identifier.

All of these links provide the potential for any data at those destinations to be brought together. If you go to the English page on wikipedia for Beatrice Webb, that includes content sourced from wikidata: https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q242666 – another instance of sharing information across different services.

Going back to ISAAR(CPF), the standard states that repositories “can more easily share or link contextual information about this source if it has been maintained in a standardized manner. Such standardization is of particular international benefit when the sharing or linking of contextual information is likely to cross national boundaries”. But as the name entry itself is down to national standards, the question is whether the NCA Rules do encourage standardisation. I would say that they do, on the whole, but with caveats, including those mentioned above. You may have others. I know that some archivists are not happy with the treatment of women’s names, such as the advice: “A woman who marries and adopts her husband’s surname is to be entered under that name.” I tend to think that it is important to include the maiden name, and I think we should consider both linking up data (links from information created before the person was married, for example) and also how end users will search – rules are no good if they act against people actually finding the information that they want.

Epithet and structure

Epithets are used by archivists, but most domains do not use them. The library world does not add epithets. We like them for adding context, and they are often very useful. However, they do add to the level of variation considerably. For our Names Project we will probably exclude the epithet from name matching (if we can – they are not always easy to isolate). With the time and tenacity, you could utilise them to help with matching, but one of the challenges with algorithmic solutions is that you have to draw the line according to your resources. Epithets are really useful, but we can never hope to standardise them. What we really need to do is to identify them as part of the structure. In EAC-CPF (the XML standard for name entities that is based upon ISAAR(CPF), information typically included in epithets is separated out semantically:

<nameEntry>

<part localType=“surname”>Emberton</part>

<part localType=“forename”>Joseph</part>

</nameEntry>

And then also included in this entry:

<occupation>

<term>Architect</term>

</occupation>

This is perfect. You can display the information together, or separately; you can search them together, or separately. Records in Context (RiC) has sought to provide a conceptual model that brings together ICA archival standards. It is not a set of cataloguing guidelines, but it does use the language of structured data, and to some degree Linked Data – names are ‘entities’ and they have properties and relations with other entities. It encourages the idea of separating out things like occupation (often part of our epithet) from the agent (person) so that you can, for example, link one occupation to many people. This is more feasible if we create the entries in a structured way so that you can separate these two pieces of information (a person pursues an occupation / an occupation is pursued by a person), but often we don’t do this, and our cataloguing systems don’t help us to do this.

Dividers

In many ways these are part of a name for the purposes of processing, but dividers are not really covered in most standards. Standards tend to cop out by using pipes: Charles I | 1600-1649 | King of Great Britain and Ireland. This is an agnostic stance – the dividers are up to you. NCA Rules: “In the Rules there are no mandatory conventions for punctuation and abbreviation. These will continue to conform to the house style of each repository.” For house style read “everyone do what they prefer”.

This has meant that we have a great and interesting variety of dividers. The divider diversity can be overcome programatically, but it is still another complication in terms of consistency. Have a look at the names at the bottom of this record: https://archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/data/gb982-sww. The problems are *not* because Aberystwyth have entered them incorrectly – the data is fine; they are because this record was created in a long past time (2010) of the Archives Hub’s first online data creation tool, which was fairly basic. We then attempted some global normalisation work on these older descriptions…and there’s the rub. If you write something to say ‘turn X into Y’ that usually works fine. But the more complicated it gets, the harder it is to satisfy all the data, so to speak. It is more like ‘turn P,Q,R,S,T,U,V,W,X into Y’ but if you come across A, B or C turn them into Z’. With the above example the excess of dividers is because there is punctuation within the XML record itself, but we also apply punctuation during display, as most records don’t include it. We are now working on more effective ways to standardise (which is a slow process because we don’t have many staff, whilst we also have loads of things clamouring for attention). We could have a recognised and agreed use of dividers, e.g:

Churchill, Sir Winston Leonard Spencer, 1874-1965, Knight, statesman and historian

or

Churchill, Sir Winston Leonard Spencer (1874-1965), Knight, statesman and historian

Dates in brackets seems to be the most common approach in archives, although maybe less so in other domains. Both these names can be easily matched – the dividers are not a problem. But it can get harder with various combinations of pre-titles, titles, epithets, born, died, floruit, question marks, nee, square brackets, commas, stops, semi-colons and colons. However, the ideal is that the parts of the name are created separately, and then displayed as preferred, which I come back to below.

So, what should we do?

My best advice to anyone creating names is to follow ISAAR(CPF) and to use NCA Rules, but also think about a name in a broader context and be aware of international standards and identifiers – it is great if you can include recognised identifiers if you can – VIAF or ISNI or ORCID. We want to share data with the outside world (outside of the archival domain) so we don’t want to be too focused on archival standards and ignore web standards and common ways of doing things. We have to work within the systems we have, so sometimes you cannot structure a name as you would like, but aim for consistency, semantic structure as far as you are able, and practices that are not out of step with everyone else’s practices. This means that we can more easily join our data up and create a space that researchers can navigate in infinite ways and for infinite purposes.