Archives Hub feature for May 2017

Explore descriptions relating to the Spanish Civil War on the Archives Hub.

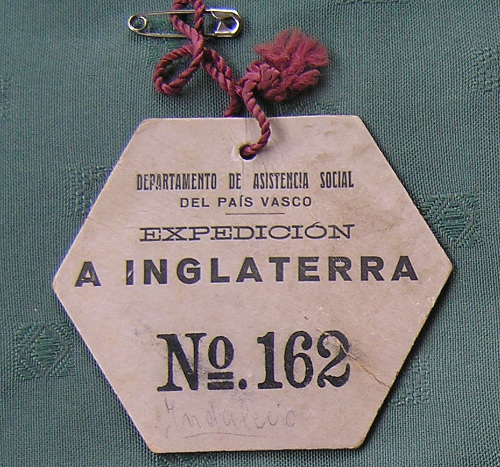

In May 1937 approximately 4,000 children, with labels pinned to their clothes, came to Southampton on board the Habana from Santurzi/Santurce, the port of Bilbo/Bilbão, fleeing the Spanish Civil War and its consequences.

The Spanish Second Republic had been established in 1931, with an ambitious agenda to eliminate deeply-rooted social and cultural inequalities. The republican programme encompassed land and education reform, improved rights for women, restructuring the army, and granting autonomy to Catalonia and the Basque Country. Threatened by far-reaching change, diverse political groupings aligned themselves in the so-called ‘two Spains’. The ensuing civil war lasted three years, with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy helping one faction, Communist Russia the other, with Chamberlain’s Britain leading a policy of appeasement among Western democratic nations. In this bitter conflict, there was a third Spain, which did not want to take up arms, but to live in peace. War, hunger, revolution, counter-revolution, denunciations, persecution, summary trials and executions, and mass repression often resulted in the disintegration of family and community life, desolating a country and forcing thousands of its people into exile.

On 26 April 1937, General Franco attacked Guernica and Durango, one of the first bombings of a civilian population in Europe. In the wake of this, the Basque government and the National Joint Committee for Spanish Relief, co-ordinating relief in the UK, organised the evacuation of children from the north front of the war zone. The British government had a policy of non-intervention in Spain and, whilst it permitted the children to entry the UK, no public funds were made available for the expedition, nor for the care of the children once they arrived. Their maintenance was provided for entirely by private funds and those raised by voluntary groups and organisations, under the overall co-ordination of the Basque Children’s Committee.

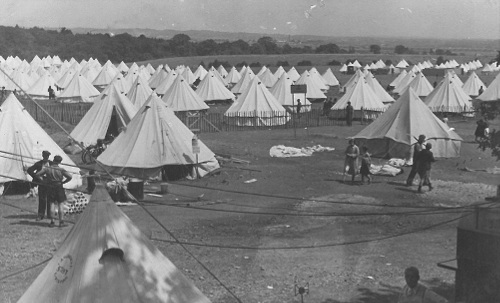

On arrival at Southampton, the children were sent to a hastily constructed camp at North Stoneham, near Eastleigh, which now forms part of Southampton Airport.

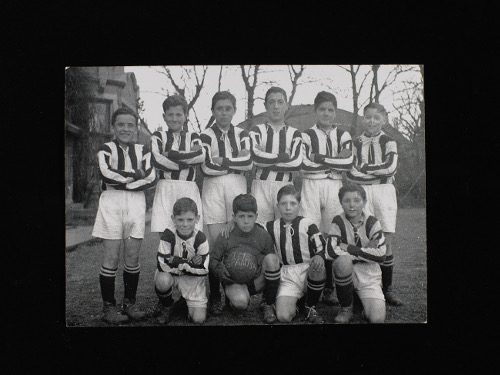

This was the children’s temporary home until they were dispersed to be cared for by the Catholic Church, the Salvation Army, which accommodated children in a hostel in London, or in the so-called “colonies” set up by local committees across the country. Eventually over ninety “colonies” were established, each housing between 20 to 50 children. Ranging from stately homes to converted workhouses, the “colonies” were run on donations. When the initial funding for them began to dry up, the niños were drawn into helping raise funds by performing concerts and shows and by taking part in football matches with local teams.

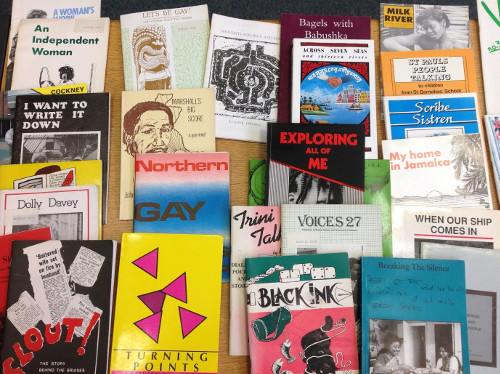

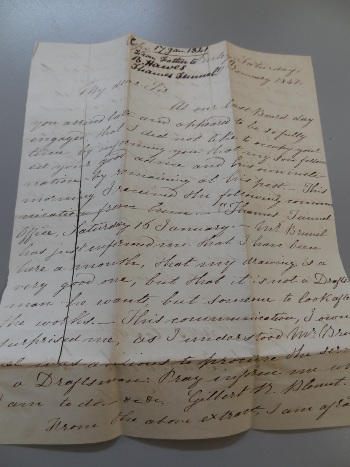

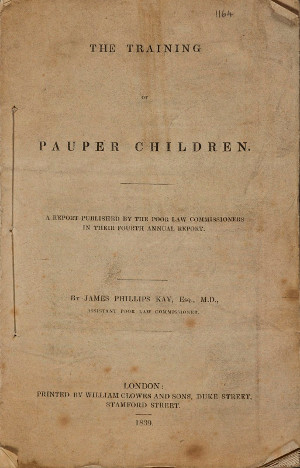

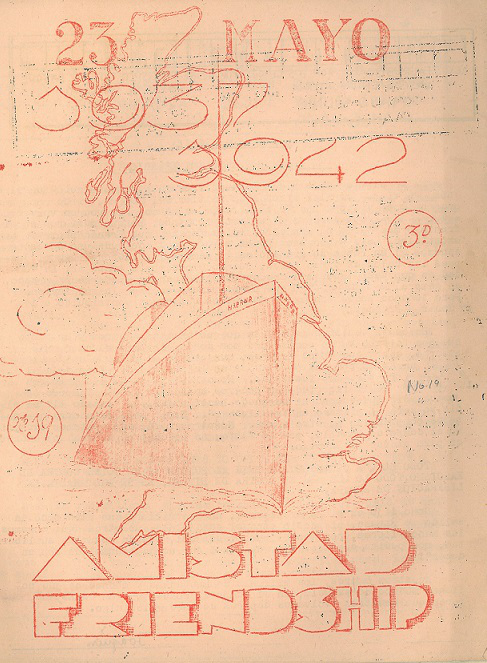

The children who came on board the Habana brought very little in the way of personal possessions with them, but they brought memories of the conflict and a sense of their identity. Aside from the shows and concerts where the children dressed in national costume, sang songs or performed dances from home, publications such as Amistad, one of the newsletters produced by the children themselves, were a means for them to remember. Conceived as an informative monthly publication, the newsletter contains pieces describing life in the Basque region, the bombing of Guernica, reflections on war and the journey on the Habana.

The Special Collections at the Hartley Library, University of Southampton, holds archives for the Basque Children of ‘37 Association UK (MS 404), which was founded in 2002 to ensure that the legacy of the Basque children was not forgotten, together with small collections relating to Basque child refugees (MS 370) that have come from individuals. Further details on the collection can be found on the website at:

http://www.southampton.ac.uk/archives/resources/basquecollections.page

There are also a series of interviews of the niños vascos conducted as part of an oral history project undertaken by the University of Southampton:

http://www.southampton.ac.uk/archives/projects/losninos.page

Karen Robson

Senior Archivist

Hartley Library, University of Southampton

Related:

Browse the University of Southampton Special Collections on the Archives Hub.

Archives Hub Themed Collection: Open Lives. The OpenLives project documented the experiences of Spanish migrants returning to Spain after settling in the UK. Researchers from the University of Southampton collected oral testimony, images and other ephemera.

All images copyright the Hartley Library, University of Southampton and

reproduced with the kind permission of the copyright holder.