We would like to share some of the results of our annual online survey, which we run each year, over a 3-4 week period. We aim for about 100 responses (though obviously more would be very welcome!), and for this survey we got 92 responses. We create a pop-up invitation to fill out the survey – something we do not like to do, but we do feel that it attracts more responses than a simple link.

Context

We have a number of questions that are replicated in surveys run for Zetoc and Copac, two bibliographic JISC-funded Mimas services, and this provides a means to help us (and our funders) look at all three services together and compare patterns of use and types of user.

This year we added four questions specifically designed to help us with understanding users of the Hub and to help us plan our priorities.

We aim to keep the number of questions down to about 12 at the most, and ensure that the survey will take no longer than 10 minutes to complete. But we also want to provide the opportunity for people to spend longer and give more feedback if they wish, so we combine tick lists and radio boxes with free text comments boxes.

We take the opportunity to ask whether participants would be willing to provide more feedback for us, and if they are potentially willing, they provide their email address. This gives us the opportunity to ask them to provide more feedback, maybe by being part of a focus group.

Results of the Survey

Profile

- The vast majority of respondents (80%) are based in the UK for their study and/or work.

- Most respondents are in the higher education sector (60%). A substantial number are in the Government sector and also the heritage/museum sector.

- 20% of those using the Hub are students – maybe less than we would hope, but a significant number.

- 10% are academics – again, less than we would hope, but it may be that academics are less willing to fill in a survey.

- 50% are archivists or other information professionals. This is a high number, but it is important to note that it includes use of the Hub on behalf of researchers, to answer their enquiries, so it could be said to represent indirect use by researchers.

- The majority of respondents use the service once or twice a month, although usage patterns were spread over all options, from daily to less than once a month, and it is difficult to draw conclusions from this, as just one visit to the Hub website may prove invaluable for research.

- A significant percentage – 26% – find the Hub ‘neither easy nor difficult’ to use, and 3% of the respondents found it difficult to use, indicating that we still need to work on improving usability (although note that a number of comments were positive about ease of use) .

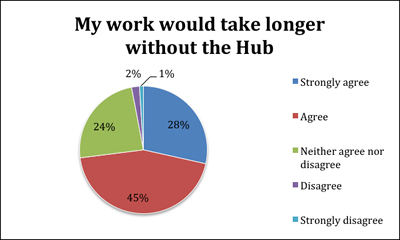

- 73% agree their work would take longer without the Hub, which is a very positive result and shows how important it is to be able to cross-search archives in this way.

- A huge majority – 93% – would recommend the Hub to others, which is very important for us. We aim to achieve 90% positive in this response, as we believe that recommendations are a very important means for the Hub to become more widely known.

Subject Areas

We spent a significant amount of time creating a list of subjects that would give us a good indication of disciplines in which people might use the Hub. The results were:

-

- History 47

- Library & Archive Studies 33

- English Literature 17

- Creative & Performing Arts 16

- Education & Research Methods 10

- Predominantly Interdisciplinary 9

- Geography & Environment 5

- Political Studies & International Affairs 5

- Modern Languages and Linguistics 4

- Physical Sciences 4

- Special Collections 4

- Architecture & Planning 3

- Biological & Natural Sciences 3

- Communication & Media Studies 3

- Medicine 3

- Theology & Philosophy 3

- Archaeology 2

- Engineering 2

- Psychology & Sociology 2

- Agriculture 1

- Law 1

- Mathematics 1

- Business & Management Studies 0

- History is, not surprisingly, the most common discipline, but literature, the arts, education and also interdisciplinary work all feature highly.

- There is a reasonable amount of use from the subjects that might be deemed to have less call for archives, showing that we should continue to promote the Hub in these areas and that archives are used in disciplines where they do not have a high profile. It would be very valuable to explore this further.

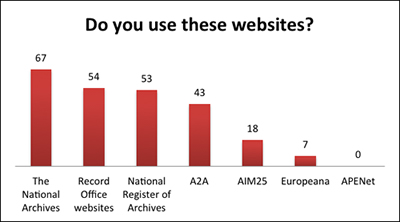

- The Hub is often used along with other archival websites, particularly The National Archives and individual record office websites, but a significant number do not use the websites listed, so we cannot assume prior knowledge of archives.

- It would be interesting to know more about patterns of use. Do researchers try different websites, and in what order to they visit them? Do they have a sense of what the different sites offer?

- There is still low use of the European aggregators, Europeana and APENet, although at present UK archives are not well represented on these services and arguably they do not have a high profile amongst researchers (the Hub is not yet represented on these aggregators).

Subsequent activities

- It is interesting to note that 32% visit a record office as a result of using the Hub, but 68% do not. It would be useful to explore this further, to understand whether the use of the Hub is in itself enough for some researchers. We do know that for some people, the description holds valuable information in and of itself, but we don’t know whether the need to visit a record office, maybe some distance away, prevents use of the archives when they might be of value to the researcher.

What is of most value?

- We asked about what is important to researchers, looking at key areas for us. The results show that comprehensive coverage still tops the polls, but detailed descriptions also continue to be very important to researchers, somewhat in opposition to

the idea of the ‘quick and dirty’ approach. More sophisticated questioning might draw out how useful basic descriptions are compared with no description and what sort of level of detail is acceptable.

the idea of the ‘quick and dirty’ approach. More sophisticated questioning might draw out how useful basic descriptions are compared with no description and what sort of level of detail is acceptable. - Links to digital content and information on related material are important, but not as important as adding more descriptions and providing a level of detail that enables researchers to effectively assess archives.

- Searching across other cultural heritage resources at the same time is maybe surprisingly less of a priority than content and links. It is often assumed that researchers want as much diverse information as possible in a ‘one-stop shop’ approach, but maybe the issues with things like the usability of the search, navigation, number of results and relevance ranking of results illustrate one of the main issues – creating a site that holds descriptions and links to very varied content and still ensuring it is very easily understandable and researchers know what they are getting.

- The regional search was not a high priority but a significant medium priority, and it might be argued that not all researchers would be interested in this, but some would find it particularly useful, and many archivists would certainly find it helpful in their work

- We provided a free text box for participants to say what they most valued. The ability to search across descriptions, which is the most basic value proposition of the Hub, came out top, and breadth of coverage was also popular, and could be said to be part of the same selling point.

- It was interesting to see that some respondents cited the EAD Editor as the main strength for them, showing how important it is to provide ways for archivists to create descriptions (it may be thought that other means are at their disposal, but often this is not the case).

- Six people referred to the importance of the Hub for providing an online presence, indicating that for some record offices, the Hub is still the only way that collections are surfaced on the Web.

What would most improve the Hub?

- We had a diversity of responses to the question about what would most improve the Hub, maybe indicating that there are no very obvious weaknesses, which is a good thing. But this does make it difficult for us to take anything constructive from the answers, because we cannot tell whether there is a real need for a change to be made. However, there were a few answers that focused on the interface design, and some of these issues should be addressed by our new ‘utility bar’ which is a means to more clearly separate the description from the other functions that users can then perform, and should be implemented in the next six months.

Conclusions

The survey did not throw up anything unexpected, so it has not materially affected our plans for development of the Hub. But it is essentially an endorsement of what we are doing, which is very positive for us. It emphasised the importance of comprehensive coverage, which is something we are prioritising, and the value of detailed descriptions, which we facilitate through the EAD Editor and our training opportunities and online documentation. Please contact us if you would like to know more.