Archives Hub feature for January 2025

Bethlem Museum of the Mind is dedicated to using the historic collections of the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust to display and discuss issues in mental health, and to celebrate the achievements of people dealing with severe mental health issues.

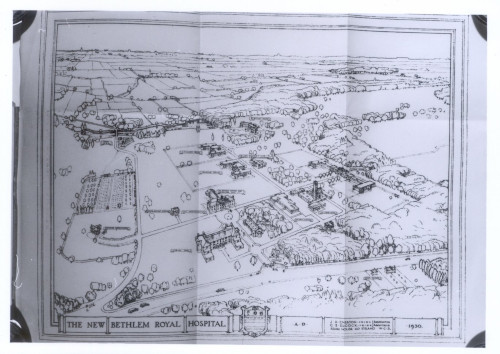

The Museum is based in the former administration building of Bethlem Royal Hospital, today located in a 200 acre site in Beckenham, south London. Since 1948 the Hospital has been a specialist NHS psychiatric hospital, and today supplies 400 beds to the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, which provides modern psychiatric care to those in need in the London Boroughs of Lambeth, Southwark, Lewisham and Croydon, as well as certain national services.

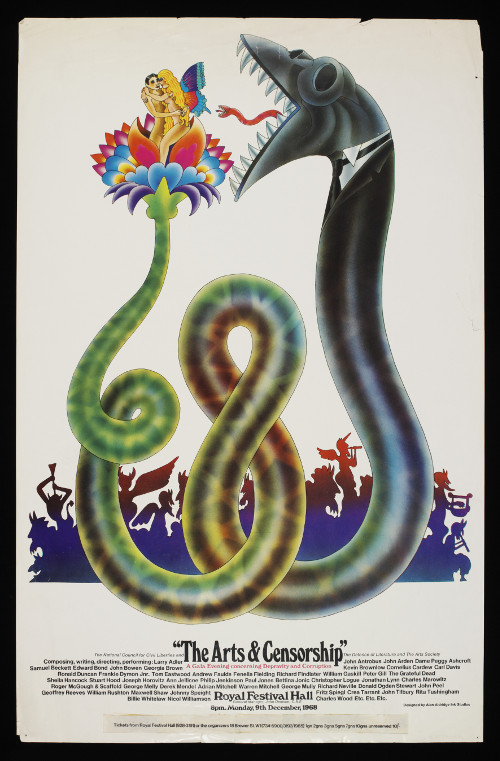

However, the Hospital has a past that stretches back over 750 years as Europe’s oldest specialist psychiatric hospital, across four different sites in London. Although there are many phases in Bethlem’s history, it’s early reputation for cruel treatment saw it christened ‘Bedlam’ by the Londoners living around it, and the entwining histories of the real place and the imagined place of chaos and confusion is something the Museum tries to unpick.

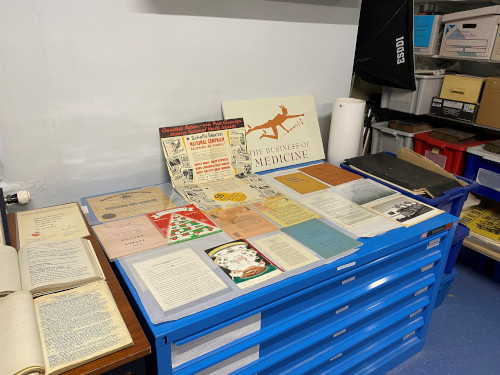

The Museum of the Mind’s archive collections consist of the historic records of Bethlem Royal Hospital; The Maudsley Hospital, a specialist acute psychiatric hospital in south London which dates from 1923; and Warlingham Park Hospital, the Borough Asylum for Croydon, founded in 1903 and closed in 1999. These have been managed by a specialist archivist since the 1960s, and coexist in the Museum collections together with a collection of over 1000 artworks by patients, (viewable here), and more than 800 objects that reflect the history of the Trust.

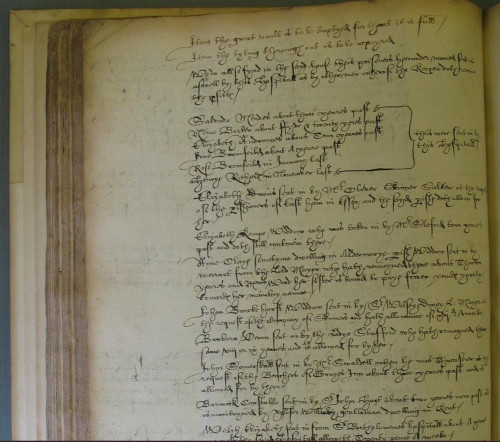

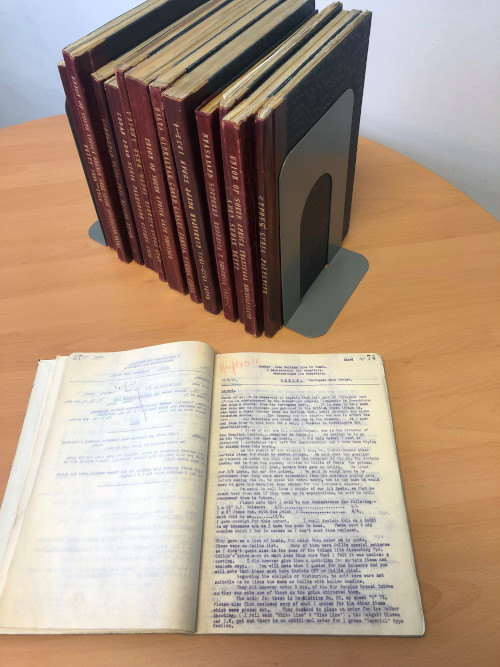

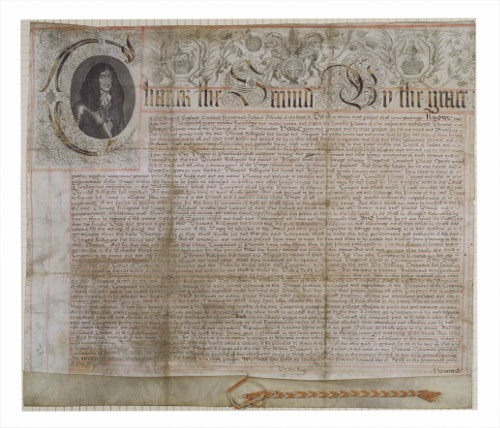

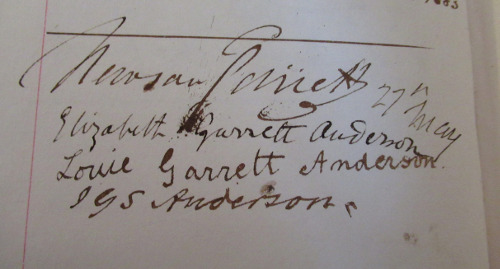

The records for Bethlem date back to its incorporation as a civic charity in 1557 under the watchful eye of the Board of Governors of Bridewell and Bethlem Hospitals, a set of grandees drawn from the ranks of the City of London Corporation. The oldest set of records are the minutes of the Board of Governors, held under our reference BCB, and our oldest record of any patients of Bethlem is a rather unassuming list from 1598.

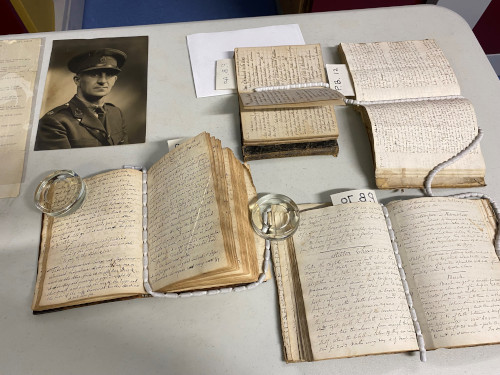

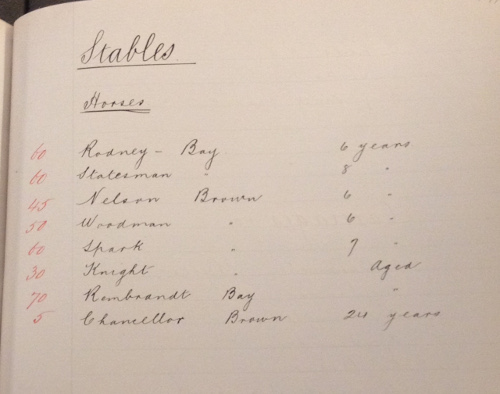

As record keeping practices developed, one can see the emergence of something like a modern psychiatric hospital at Bethlem – admission records are created from the 1680s, and casebooks arrive in 1815. However all these records are in some ways problematic, as they express the patient experience through the lens of the Hospital, very often using out of date terminology and a contemporary attitude that seems woefully short of best practice today.

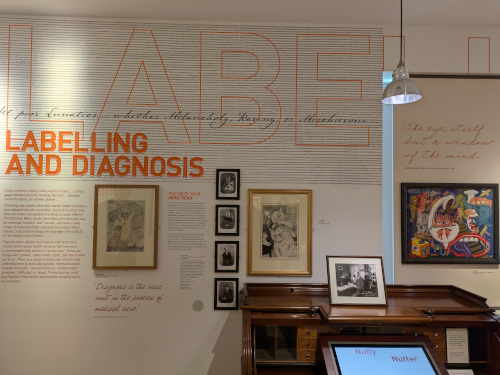

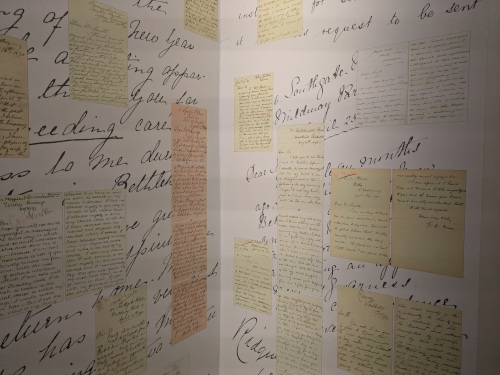

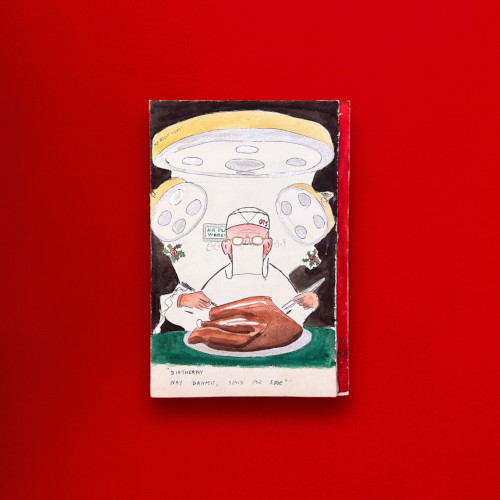

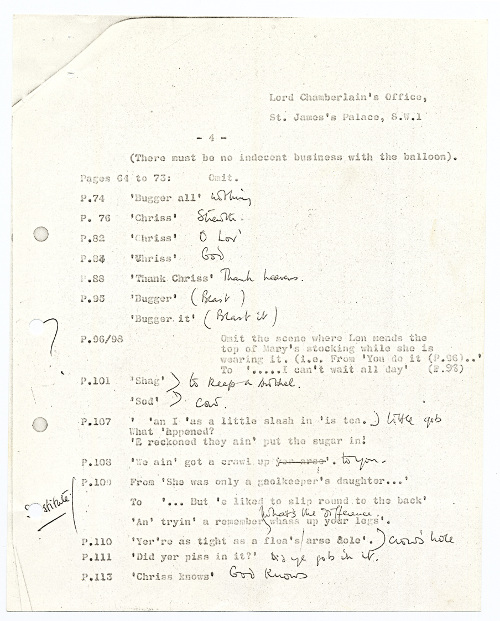

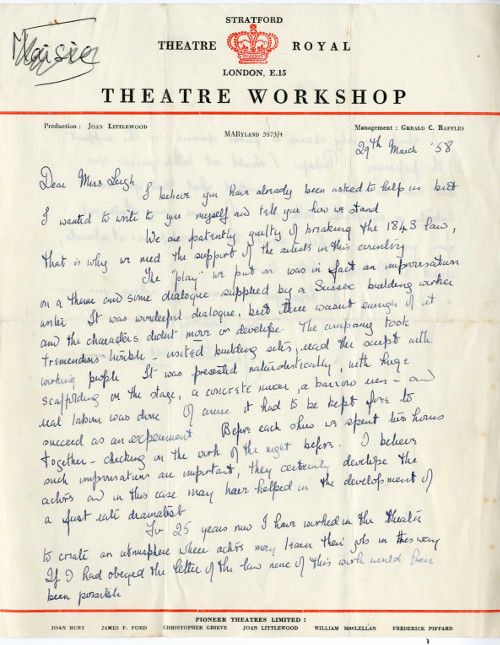

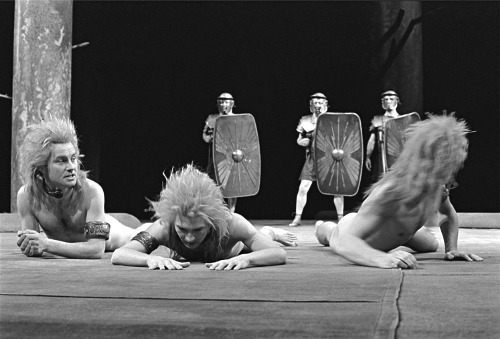

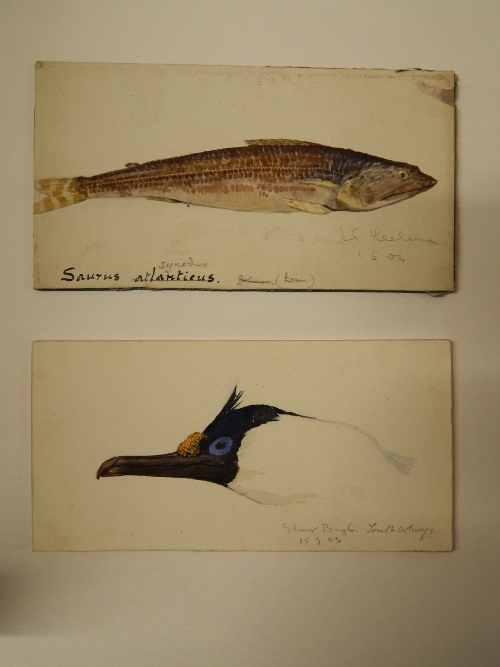

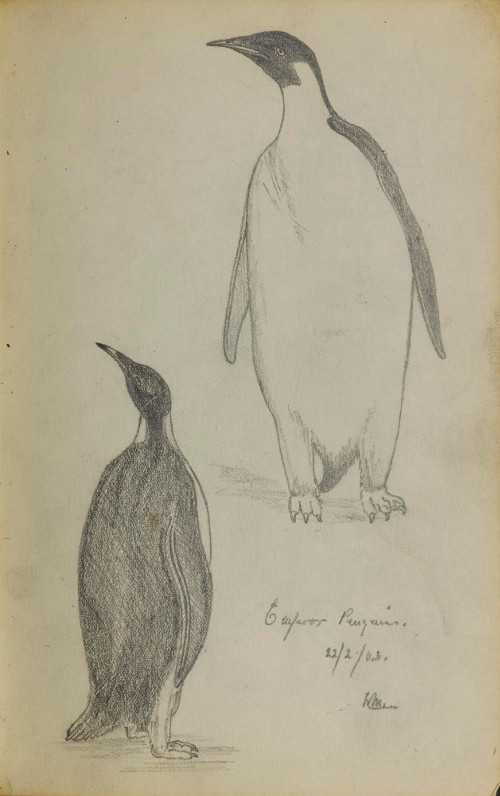

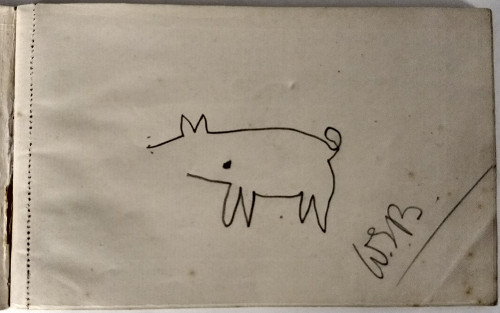

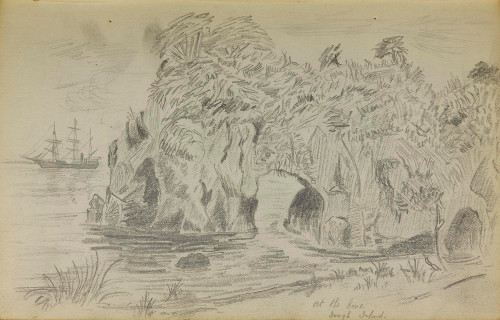

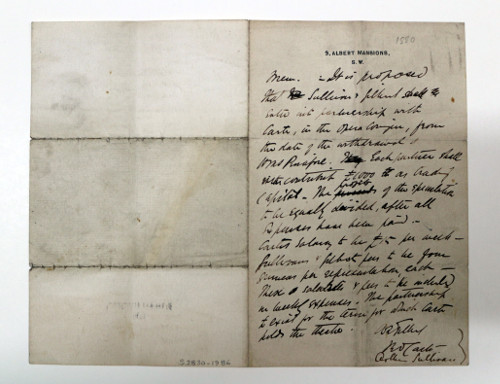

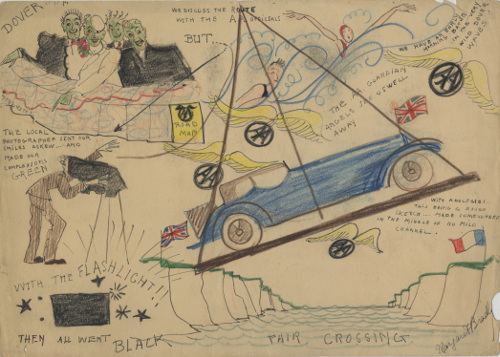

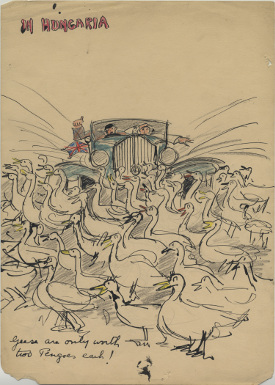

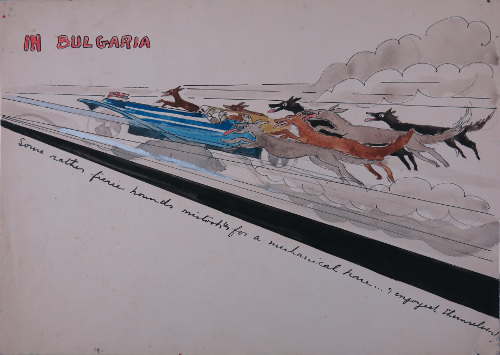

The Museum has therefore made the choice to try and address these shortcomings. One of the sections in the permanent displays looks at the limitations of language and medical jargon, especially around diagnosis. When the archives are used in the displays it is not done uncritically, but with an acknowledgement of the shortcomings of them as sources. Where we can, we have extracted the patient voice from smaller items in the casebooks, like letters and photographs, where a different, more personal, story can be found. The Museum also utilises the artwork it has collected to display, and celebrate, the voices of people with lived experience. Sometimes this voice directly clashes with the professional tone of the organisational record, but we believe that it is important to recognise a multiplicity of experience in this area. It’s also important to recognise that elements like ‘restraint’ (another section in the Museum) have both a past and a present in mental health treatment, and to speak of these issues as if they have vanished would be to hide a more complicated, if troubling, truth.

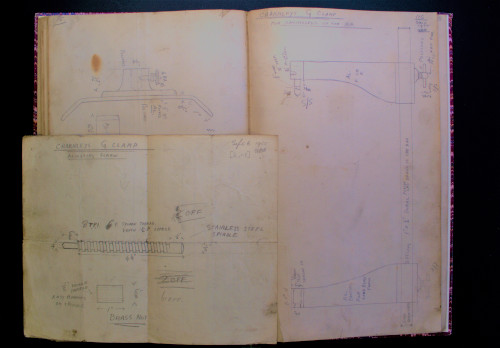

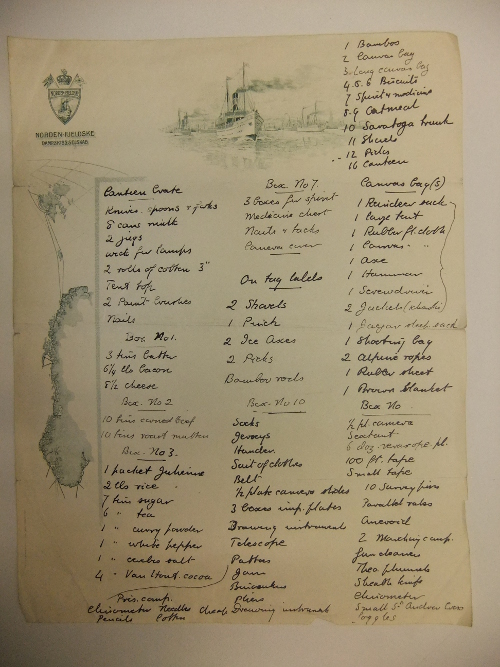

The records in the archive cover 450 years of mental health treatment, and take up some 250 metres of shelving for plans, images, patient and staff records, as well as the committee records of the groups that administrated the hospitals. The records are catalogued to the Australian Series System, which is a little different to standard UK cataloguing practices, so what is on Archives Hub is really an indicator of what we hold rather than a comprehensive list – see the catalogue here.

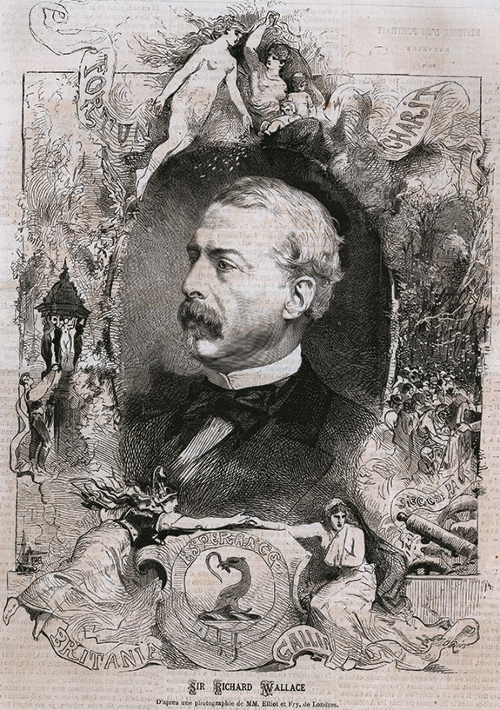

In providing safe and professional storage and access the archivist fulfils the public records function for the NHS Trust, but also supports the displays of the Museum, the learning and outreach programme which spoke to over 3,000 students in 2023, and bespoke history projects like Change Minds, which worked with people with lived experience to investigate the lives of people who were treated in the Victorian Bethlem. We feel this work, in re-examining and investigating the lives of people who were in the hospital outside of the context of their mental health issues, to be amongst the most important things we do. You can see some of our blogs on this project here.

The Museum has put a wealth of historical resources online. The patient and staff records up to 1918 have been digitised and indexed on Find My Past and British Online Archives, allowing remote access to thousands of genealogists and academic researchers. The Museum has digitised some of its archives itself, most notably the Board of Governors Minute Books up to the 1800s, and the collection of Lantern slides of the Edward O’Donoghue, the Chaplain and first historian of the Hospital, which can be viewed via the catalogue under the series references BCB and LSC. There are also digital resources linked to the main website of the Museum, particularly in the ‘learning’ section, which deal with different times and hospitals: https://museumofthemind.org.uk/learning .

The Museum is open Wednesday to Saturday 9.30am to 5.00pm without appointment and free to all visitors (last admission at 4.30pm). The archives are available by appointment with the archivist, potentially Monday to Friday 10am to 4.30pm. Our website covers all of this at https://museumofthemind.org.uk/ , and you can reach the archivist at https://museumofthemind.org.uk/contact (select ‘archives’ from the drop down menu).

David Luck, Archivist

Bethlem Museum of the Mind

Bethlem Royal Hospital

Related

Bethlem Royal Hospital (1553-2018)

Maudsley Hospital (1868-2018)

Warlingham Park Hospital (1897-1995)

Bridewell and Bethlem Hospitals (1559-1952)

Descriptions of other collections held by Bethlem Museum of the Mind can be found on Archives Hub here: https://archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/search/locations/46a09886-cc03-3ae3-8e40-dfa9977f163a

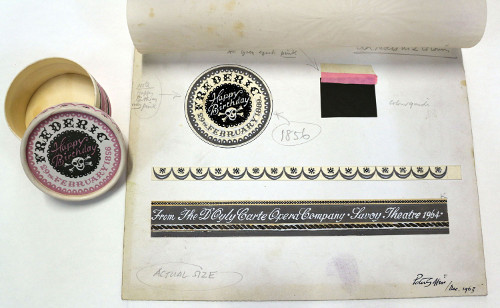

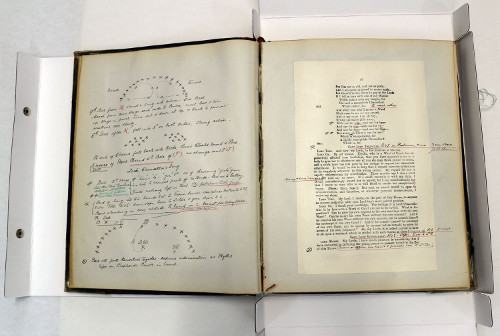

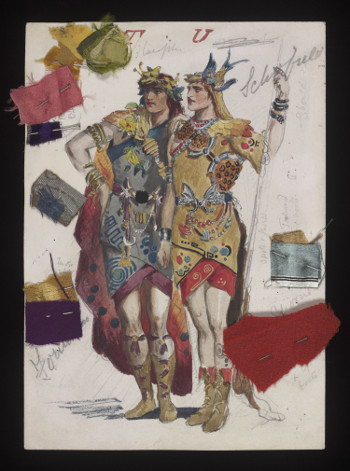

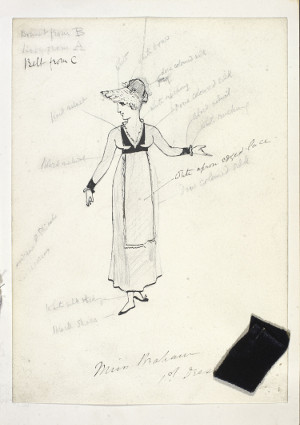

All images copyright Bethlem Museum of the Mind. Reproduced with the kind permission of the copyright holders.