The UK Archives Discovery Network (UKAD) recently advertised our up and coming Forum on the archives-nra listserv. This prompted one response to ask whether ‘resource discovery’ is what we now call cataloguing and getting the catalogues online. The respondent went on to ask why we feel it necessary to change the terminology of what we do, and labelled the term resource discovery as ‘gobledegook’. My first reaction to this was one of surprise, as I see it as a pretty plain talking way of describing the location and retrieval of information , but then I thought that it’s always worth considering how people react and what leads them to take a different perspective.

It made me think that even within a fairly small community, which archivists are, we can exist in very different worlds and have very different experiences and understanding. To me, ‘resource discovery’ is a given; it is not in any way an obscure term or a novel concept. But I now work in a very different environment from when I was an archivist looking after physical collections, and maybe that gives me a particular perspective. Being manager of the Archives Hub, I have found that a significant amount of time has to be dedicated to learning new things and absorbing new terminology. There seem to be learning curves all over the place, some little and some big. Learning curves around understanding how our Hub software (Cheshire) processes descriptions, Encoded Archival Description , deciding whether to move to the EAD schema, understanding namespaces, search engine optimisation, sitemaps, application programming interfaces, character encoding, stylesheets, log reports, ways to measure impact, machine-to-machine interfaces, scripts for automated data processing, linked data and the semantic web, etc. A great deal of this is about the use of technology, and figuring out how much you need to know about technology in order to use it to maximum effect. It is often a challenge, and our current Linked Data project, Locah, is very much a case in point (see the Locah blog). Of course, it is true that terminology can sometimes get in the way of understanding, and indeed, defining and having a common understanding of terms is often itself a challenge.

My expectation is that there will always be new standards, concepts and innovations to wrestle with, try to understand, integrate or exclude, accept or reject, on pretty much a daily basis. When I was the archivist at the RIBA (Royal Institute of British Architects), back in the 1990’s, my world centered much more around solid realities: around storerooms, temperature and humidity, acquisitions, appraisal, cataloguing, searchrooms and the never ending need for more space and more resources. I certainly had to learn new things, but I also had to spend far more time than I do now on routine or familiar tasks; very important, worthwhile tasks, but still largely familiar and centered around the institution that I worked for and the concepts terminology commonly used by archivists. If someone had asked me what resource discovery meant back then, I’m not sure how I would have responded. I think I would have said that it was to do with cataloguing, and I would have recognised the importance of consistency in cataloguing. I might have mentioned our Website, but only in as far as it provided access through to our database. The issues around cross-searching were still very new and ideas around usability and accessibility were yet to develop.

Now, I think about resource discovery a great deal, because I see it as part of my job to think of how to best represent the contributors who put time and effort into creating descriptions for the Hub. To use another increasingly pervasive term, I want to make the data that we have ‘work harder’. For me, catalogues that are available within repositories are just the beginning of the process. That’s fine if you have researchers who know that they are interested in your particular collections. But we need to think much more broadly about our potential global market: all the people out there who don’t know they are interested in archives – some, even, who don’t really know what archives are. To reach them, we have to think beyond individual repositories and we have to see things from the perspective of the researcher. How can we integrate our descriptions into the ‘global information environment’ in a much more effective way. A most basic step here, for example, is to think about search engine optimisation. Exposing archival descriptions through Google, and other search engines, has to be one very effective way to bring in new researchers. But it is not a straightforward exercise – books are written about SEO and experts charge for their services in helping optimise data for the Web. For the Archives Hub, we were lucky enough to be part of an exercise looking at SEO and how to improve it for our site. We are still (pretty much as I write) working on exposing our actual descriptions more effectively.

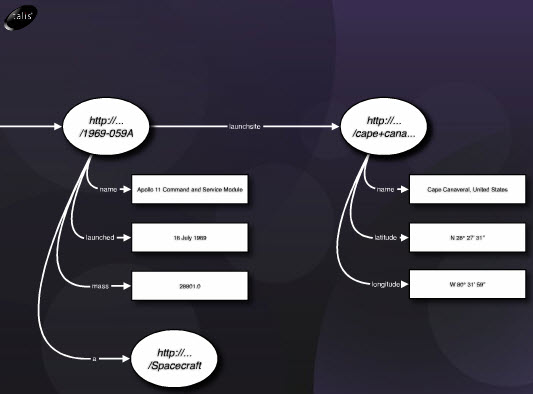

Linked Data provides another whole world of unfamiliar terminology to get your head round. Entities, triples, URI patterns, data models, concepts and real world things, sparql queries, vocabularies – the learning curve has indeed been steep. Working on outputting our data as RDF (a modelling framework for Linked Data) has made me think again about our approach to cataloguing and cataoguing standards. At the Hub, we’re always on about standards and interoperability, and it’s when you come to something like Linked Data, where there are exciting possibilities for all sorts of data connections, well beyond just the archive community, that you start to wish that archivists catalogued far more consistently. If only we had consistent ‘extent’ data, for example, we could look at developing a lovely map-based visualisation showing where there are archives based on specific subjects all around the country and have a sense of where there are more collections and where there are fewer collections. If only we had consistent entries for people’s names, we could do the same sort of thing here, but even with thesauri, we often have more than one name entry for the same person. I sometimes think that cataloguing is more of an art than a science, partly because it is nigh on impossible to know what the future will bring, and therefore knowing how to catalogue to make the most of as yet unknown technologies is tricky to say the least. But also, even within the environment we now have, archivists do not always fully appreciate the global and digital environment which requires new ways of thinking about description. Which brings me back to the idea of whether resource discovery is another term for cataloguing and getting catalogues online. No, it is not. It is about the user perspective, about how researchers locate resources and how we can improve that experience. It has increasingly become identified with the Web as a way to define the fundamental elements of the Web: objects that are available and can be accessed through the Internet, in fact, any concept that has an identity expressed as a URI. Yes, cataloguing is key to archives discovery, cataloguing to recognised standards is vital, and getting catalogued online in your own particular system is great…but there is so much more to the whole subject of enabling researchers to find, understand and use archives and integrating archives into the global world of resources available via the Web.