IIIF is a model for presenting and annotating digital content on the Web, including images and audio/visual files. There is a very active global community that develops IIIF and promotes the principles of open, shareable content. One of the strengths of IIIF is the community, which is a diverse mix of people, including developers and information professionals.

Images are fundamental carriers of information. They provide a huge amount of value for researchers, helping us understand history and culture. We interact with huge amounts of images, and yet we do not always get as much value out of them as we might. Content may be digitised, but it is often within silos, where the end user has to go to a specific website to discover content and to view a specific image, it is not always easy or possible to discover, gather together, compare, analyse and manipulate images.

IIIF is a particularly useful solution for cultural heritage, where analysis of images is so important. A current ‘Towards a National Collection’ project has been looking at practical applications of IIIF.

The IIIF Solution

Exactly what IIIF enables depends upon a number of factors, but in general it enables:

Deep zoom: view and zoom in closely to see all the detail of an image

Sequencing: navigate through a book or sequence of archival materials

Comparisons: bring images together and put them side-by-side. This can enable researchers to bring together images from different collections, maybe material with the same provenance that has been separated over time.

Search within text: work with transcriptions and translations

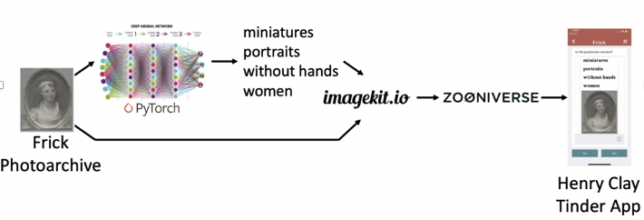

Connections: connect to resources such as Wikidata

Use of different IIIF viewers: different viewers have their own features and facilities.

How It Works

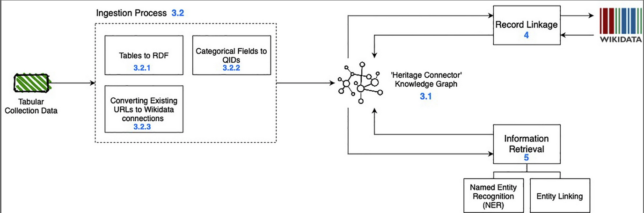

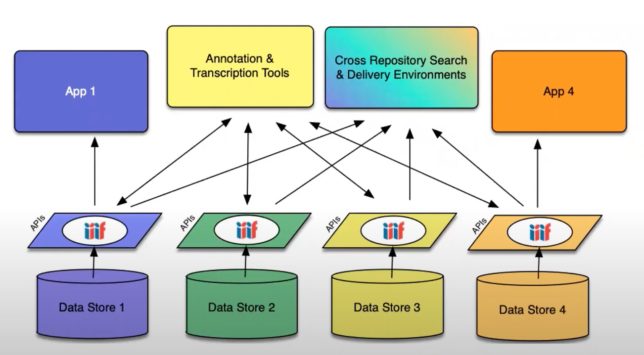

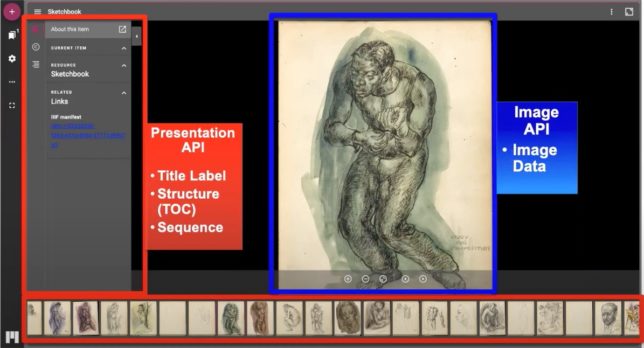

The IIIF community tends to talk in terms of APIs. These can be thought of as agreed and structured ways to connect systems. If you have this kind of agreement then you can implement different systems, or parts of systems, to work with the same content, because you are sticking to an agreed structure. The basic principle is to store an image once (on a IIIF server) and be able to use it many times in many contexts.

IIIF is like a a layer above the data stores that host content. The images are accessed through that IIIF layer – or through the IIIF APIs. This enables different agents to create viewers and tools for the data held in all the stores.

There are a few different APIs that make up the IIIF standard.

Image API

This API delivers the content (or pixels). The image is delivered as a URL, and the URL is structured in an agreed way.

Presentation API

This delivers information on the presentation of the material, such as the sequence of a book, for example, or a bundle of letters, and metadata about the object.

Search API

Allows searching within the text of an object.

Authentication API

Allows materials to be restricted by audience. So, this is useful for sensitive images or images under copyright that may have restrictions.

IIIF viewer

As IIIF images are served in a standard way, any IIIF viewer can access them. Examples of IIIF viewers:

The Universal Viewer: https://universalviewer.io/

Mirador: https://mirador-dev.netlify.app/tests/integration/mirador/

Archival IIIF: https://archival-iiif.github.io/

Storiiies digital storytelling: https://storiiies.cogapp.com/#storiiies

There are a whole host of viewers available, with various functionality. Most will offer the basics of zooming and cropping. There does seem to be a question around why so many viewers are needed. It might be considered a better approach for the community to work on a limited group of viewers, but this may be a politically driven desire to own and brand a viewer. In the end, a IIIF viewer can display any IIIF content, and each viewer will have its own features and functionality.

To find out more about how researchers can benefit from IIIF, you may like to watch this presentation on YouTube (59m): Using IIIF for research

Some Examples

In many projects, the aim is to digitise key materials, such as artworks of national importance and rare books and manuscripts, in order to provide a rich experience for end users. For instance, the Raphael Cartoons at the V&A are now available to explore different layers and detail, even enabling the infra-red view and surface view, to allow researchers to study the paintings in great depth. Images can easily be compared within your own workspace, by pulling in other IIIF images.

What is the Archives Hub planning to do with IIIF?

Hosting content: We are starting a 15 month project to explore options for hosting and delivering content. Integral to this project will be providing a IIIF Image API. As referenced above, this will mean that the digital content can be viewed in any IIIF viewer, because we will provide the necessary URLs to do so. One of the barriers for many archives is that images need to be on a IIIF server in order to utilise the Image API. It may be that Jisc can provide this service.

Creation of IIIF manifests: We’ll talk more about this in future blog posts, but the manifest is a part of the Presentation API. It contains a sequence (e.g. ordering of a book), as well as metadata such as a title, description, attribution, rights information, table of contents, and any other information about the objects that may be useful for presentation. We will be looking at how to create manifests efficiently and at scale, and the implications for representing hierarchical collections.

Providing an interface to manage content: This would be useful for any image store, so it does not relate specifically to IIIF. But it may have implications around the metadata provided and what we might put into a IIIF manifest.

Integrating a IIIF viewer into the Archives Hub: We will be providing a IIIF viewer so that the images that we host, and other IIIF images, can be viewed within the Archives Hub.

Assessing image quality: A key aim of this project is to assess the real-world situation of a typical archive repository in the UK, and how they can best engage with IIIF. Image resolution is one potential issue. Whilst any image can be served through the IIIF API, a lower resolution image will not give the end user the same sort of rich experience with zooming and analysing that a high resolution image provides. We will be considering the implications of the likely mix of different resolutions that many repositories will hold.

Looking at rights and IIIF: Rights are an important issue with archives, and we will be considering how to work with images at scale and ensure rights are respected.

Projects often have a finite goal of providing some kind of demonstrator showing what is possible, and they often pre-select material to work with. We are taking a different approach. We are working with a limited number of institutions, but we have not pre-selected ‘good’ material. We are simply going to try things out and see what works and what doesn’t, what the barriers are and how to overcome them. The process of ingest of the descriptive data and images will be part of the project. We are looking to consider both scalability and sustainability for the UK archive sector, including all different kinds of repositories with different resourcing and expertise, and with a whole variety of content and granularity of metadata.

Acknowledgement: This blog post cites the introductory video on IIIF which can be viewed within YouTube.