Archives Hub feature for September 2016

Browse descriptions on the Archives Hub relating to ENSA.

Erik Chisholm was born on 4 January 1904 in Glasgow. A precocious talent, at the age of fourteen Chisholm undertook early study of pianoforte, rudiments of music and harmony and counterpoint (composition) under Thomas Nisbet and Philip Halstead at the Glasgow Athenaeum School of Music (now the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland). A prize winner, Chisholm consistently performed at the top of his class despite being one of the youngest students of his year.

In 1928 he was accepted to study music at the University of Edinburgh under his friend and mentor Sir Donald Francis Tovey, gaining a BMus in 1931 and a DMus in 1934.

A lifelong vegetarian, pacifist and humanitarian, Chisholm’s music was bold and original. He was the first composer to incorporate the Scottish idiom, and particularly Gaelic aspects, into his music. His first piano concerto, an orchestral work in four movements completed whilst he was still a student, incorporates many of the evolutions and figures associated with highland bagpipe music (ceòl mòr), which has led to it becoming known as the Piobaireachd Concerto. In addition many of his solo piano works including Highland Sketches (EC/12/1/9), Scottish Airs (EC/12/1/12) and the Straloch Suite (EC/12/1/15) demonstrate a similar inspiration.

In an interview with the Cape Times newspaper in 1964 Chisholm attributed his first acquaintance with highland pibroch music as the chief turning point in his compositional career (EC/8/9).

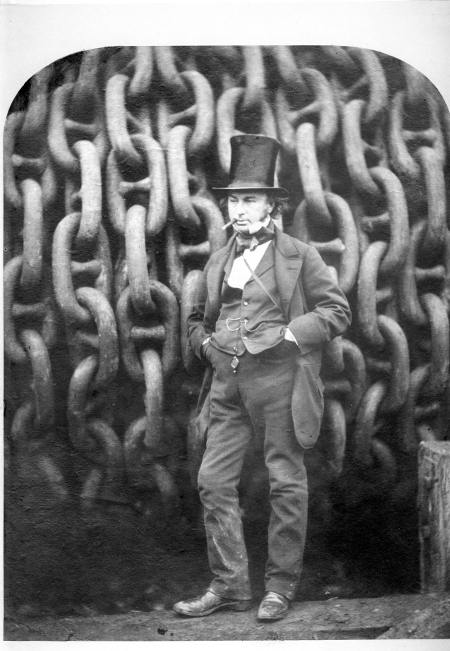

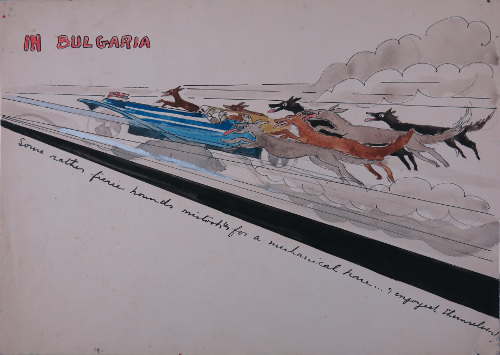

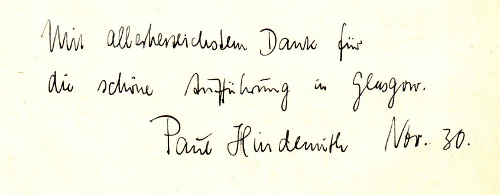

Whilst still a student, Chisholm (alongside fellow composers Francis George Scott and Pat Shannon) founded the Active Society for the Propagation of Contemporary Music, an association which transformed the classical music world in Glasgow throughout the 1930s. The Active Society brought internationally renowned composers such as Béla Bartók, Paul Hindemith and Kaikhosru Sorabji to Glasgow to conduct and perform their own works, including many UK and world premieres. One of the many jewels of the Chisholm Collection is a score autographed by Hindemith thanking Chisholm for a ‘beautiful performance in Glasgow’ dated November 1930 (EC/12/4/3).

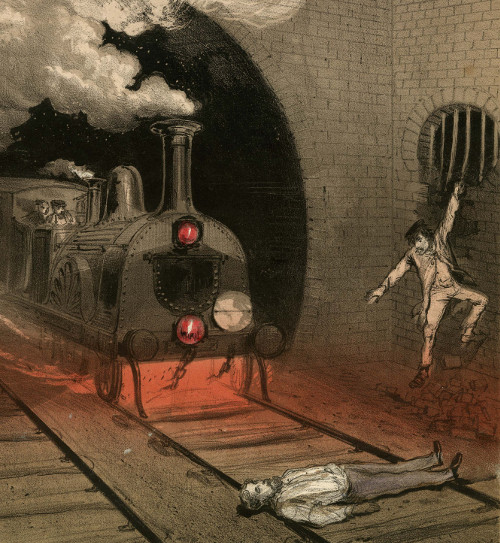

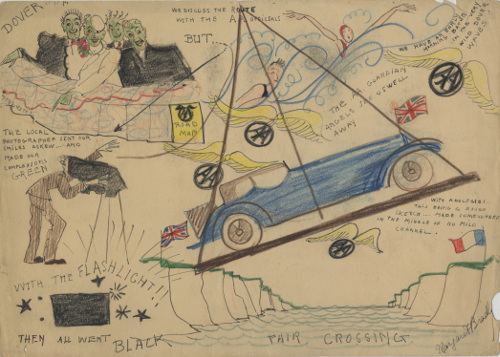

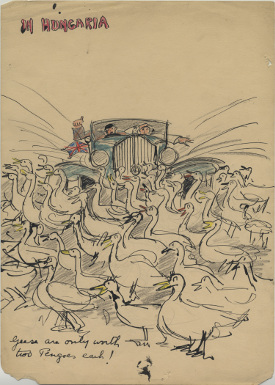

Not long after graduation from Edinburgh University with a doctorate in music, Chisholm was drafted into ENSA, the Entertainments National Service Association, where he continued to champion the cause of new music worldwide. In 1945 he was sent to India to form a full-sized symphony orchestra in Bombay (now Mumbai), presaging the formation of the Symphony Orchestra of India, still the country’s only professional orchestra, nearly sixty years later.

Whilst in India, Chisholm was introduced to Indian classical music, which left an indelible mark on him creatively. He often connected Indian ragas with Celtic music, and his Night Song of the Bards draws inspiration from both cultures, using the tuning for Rág Sohani (which is performed at night) to accent the Celtic rhythms of the allegro tempestuoso of the Second Bard. Similarly his second piano concerto, known as the Hindustani Concerto, demonstrates Chisholm’s mastery of the Indian vernacular form (EC/7/22).

After limited successes in India, Chisholm (as ENSA Musical Director for the South East Asia Command) was sent to Singapore (EC/8/4) where he founded the Singapore Symphony Orchestra with the assistance of Lord Mountbatten (EC/1/8). Singapore’s first professional full-size orchestra, the SSO was reformed in 1979 and continues to this day.

As a performer Chisholm gave the Scottish premieres of Bartók’s first and Rachmaninov’s third piano concertos, and was highly lauded for his technique. The Chisholm Collection includes a collection of references from eminent musicians and composers (EC/4/12), including William Walton, Arnold Bax and William Gillies Whittaker, amongst others, praising Chisholm for his “modernistic outlook” and “scholarly foundations” (Walton, EC/4/12/7).

In 1946, after completing his work for ENSA, Chisholm was appointed Professor of Music at the University of Cape Town and Director of the South African College of Music, and it is perhaps in this role that he is best remembered.

Chisholm revived the South African College of Music where he eventually would teach composer Stefans Grové and soprano Désirée Talbot. Using Edinburgh University as his model, Chisholm appointed new staff, extended the number of courses and introduced new degrees and diplomas. In order to encourage budding South African musicians he founded the South African National Music Press in 1948. With the assistance of the Italian baritone Gregorio Fiasconaro, Chisholm also established the college’s opera company in 1951 and opera school in 1954. In addition, Chisholm founded the South African section of the International Society for Contemporary Music (ISCM) in 1948, assisted in the founding of the Maynardville Open-Air Theatre on 1 December 1950, and pursued an international conducting career (cf. EC/7).

Chisholm did not support the prevailing apartheid policy of the South African government, and frequently found himself in opposition to authority. In protest against the cutting down of trees at the University of Cape Town campus, Chisholm refused to provide music for the upcoming graduation ceremony (EC/8/21). Dr. John Purser, Chisholm’s biographer, takes up the story:

The pressure on him to carry out his proper functions, was, however, enormous, and understandably so, and ‘appeals from tearful graduates urged him to change his mind.’ He finally appeared to capitulate, but no sooner had the students processed into the hall to the appropriate strains of Gaudeamus Igitur than the programme changed to ‘McDowell’s In Deep Woods and To an Old White Pine, sylvan arias by Handel, and concluded with March of the Tree Planters’. There were more than enough people aware of the controversy and the music to appreciate that their unrepentant professor had balanced the score. (Purser, Erik Chisholm, Scottish Modernist 1904-1965: Chasing a Restless Muse, p. 173; EC/4/11).

One of the largest series in the Erik Chisholm archive is the collection of his correspondence, and in particular his exchange of letters over more than thirty years with the infamous and controversial composer Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji. Born Leon Dudley Sorabji in 1892, like Chisholm Sorabji was a pianist / composer of precocious talent. Unlike Chisholm, however, he was largely self-taught, and his music polarised listeners and critics alike. Perhaps his most renowned work is his Opus Clavicembalisticum for solo piano, which (depending on tempo) can take around four hours to perform. At the time of its premiere under the auspices of Chisholm’s Active Society (on 1 December 1930) it was the longest piano composition in existence.

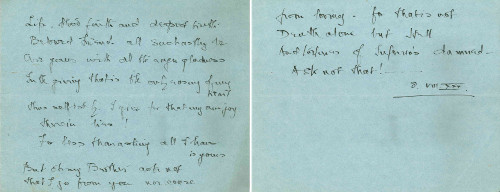

Sorabji’s correspondence with Chisholm (Chisholm’s letters to Sorabji are part of the Sorabji archive held at Warlow Farm House, Hereford – http://www.sorabji-archive.co.uk/) is extensive, containing over one-hundred and fifty letters. The relationship between composers appears to have been extremely complex, and intensely personal. In a letter dated 8th August 1930, Sorabji wrote the first of several poems dedicated and addressed to Chisholm:

Life, blood faith and deepest truth

Beloved Friend – all such as they be

Are yours with all the eager gladness

In the giving that is the only easing of my heart

Thus selfishly I give for that my own joy therein lies!

For less than asking all I have is yours

But oh my Brother ask not

That I go from you nor cease

From loving – for that is not

Death alone but Hell

And tortures of Inferno’s damned –

Ask not that! …. (EC/2/42)

As their correspondence develops, Sorabji’s largely unrequited feelings for Chisholm become more explicit. In a long letter written over several days, concluding 8th October 1930, Sorabji writes:

My dearest one what is come over me? But lately I could not get down on paper quick enough all I had to say to you and here these last few weeks … aching and longing to pour out heart and soul to you I struggle and fight with the words that cannot come to utterance. It is Beloved friend – that my affection for you is now grown so great that words cannot compass it about, and I am tongue tied and shy of utterances almost … pen tied … Forgive me for you know the “heart is sorely charged”. Oh my God! to see and touch you and look at you at this moment! (EC/2/47)

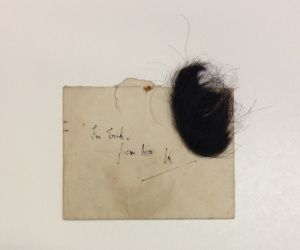

It is clear from the way in which Sorabji carefully expresses his feelings that they are not fully reciprocated by Chisholm, who was heterosexual. That said, the freeness with which Sorabji writes is extremely unusual for this period, when homosexuality was a crime punishable by incarceration and hard labour. Touchingly, the correspondence collection (which is, as yet, unpublished) also includes a lock of Sorabji’s hair sent to Chisholm at some time in the 1930s when their correspondence was most frequent (EC/2/159). They continued to write to each other until Chisholm died in 1965.

The Sorabji correspondence was mostly transcribed by Phyllis Brodie, Chisholm’s sister-in-law and Secretary of the South African Music College, and the transcripts are preserved alongside the originals in the collection (EC/2/1-181).

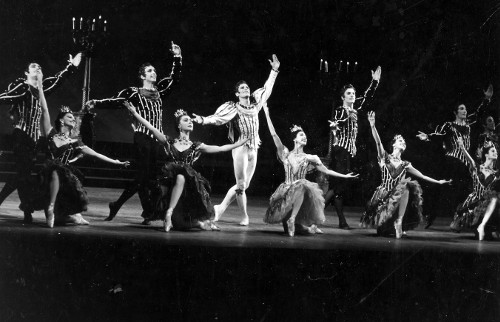

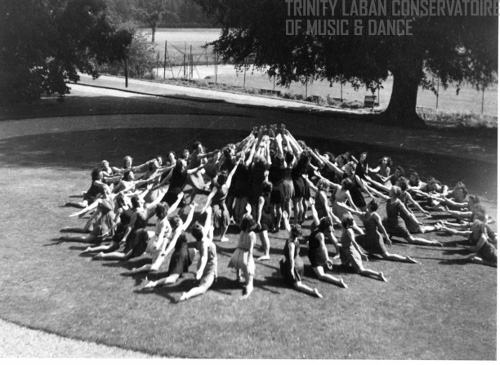

The Chisholm collection also includes material relating to Margaret Morris, wife of the Scottish Colourist J. D. Ferguson and founder of the Celtic Ballet, an early forerunner of Scottish Ballet. Chisholm’s ballets The Forsaken Mermaid (EC/12/2/1/1), The Earth Shapers (EC/12/2) and The Hoodie Craw (EC/12/2/3/2) were all choreographed by Morris and premiered by her Celtic Ballet company in the 1930s and 1940s.

Perhaps one of the most unsung gems of the collection, however, is the full score, sketches and parts of Chisholm’s unperformed opera The Importance of Being Earnest, one of his last works completed in 1963 (EC/12/3/3), two years before he died. Chisholm’s last letter to his daughter Morag dated 12th May 1965 is perhaps prescient of this:

Herewith what’s (or was) wrong with me! I’m in the office 9.30 – 1, go to bed for a couple of hours – then afternoon 3 – 5 again at the College, go to a flick or work in the evening at home at a desk – but no conducting till Sept! (EC/1/7/35)

Chisholm died less than a month later.

The Erik Chisholm Collection was acquired by the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland’s Archives & Collections from his daughter, Dr. Morag Chisholm, in January 2016. Chasing a Restless Muse: An Exhibition of Papers and Ephemera from the Erik Chisholm Collection will run from 1 September to 31 December 2016 in the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, and the complete collection catalogue can be found at http://archiveshub.ac.uk/data/gb2607-ec/1-12.

Stuart A. Harris-Logan

Archives Officer

Royal Conservatoire of Scotland

Related:

Browse the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland Collections on the Archives Hub.

All images copyright the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland and reproduced with the kind permission of the copyright holder.