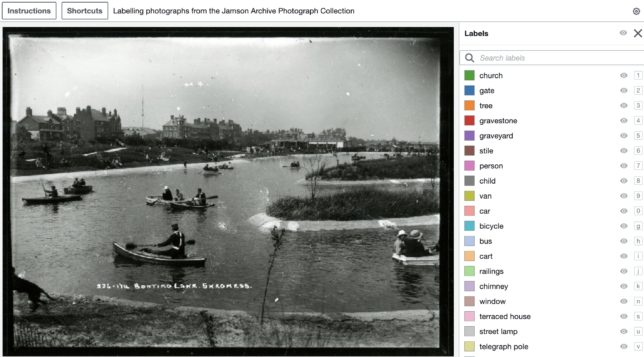

Archives Hub feature for June 2023

In 2020 the Cadbury Research Library was successful in our application for funding from the Wellcome Trust to catalogue the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) and Youth Hostel Association (YHA) archive collections. We were awarded £235,791 for a two-year project called ‘Healthy Minds and Active Bodies: the promotion of health and wellbeing by UK youth movement’. Both archive collections provide a fantastic body of material regarding work with young people and their physical and mental health, from the development of gymnasiums and outdoor activities and pursuits to educational and vocational courses.

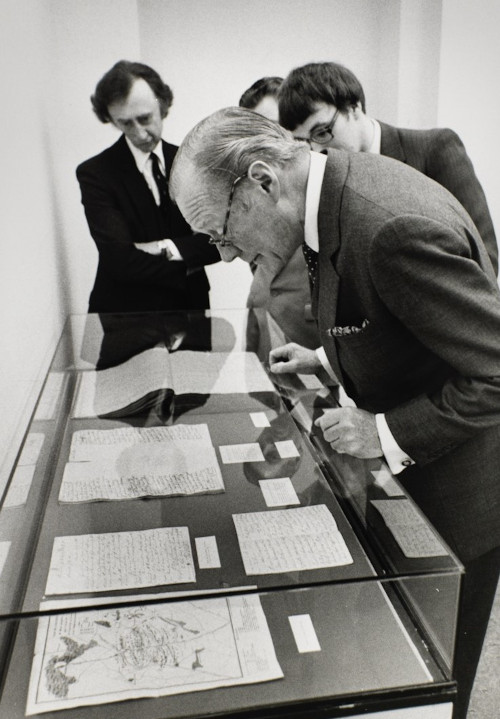

The project employed two Project Archivists, an Archives Assistant, and a part time Project Manager with the aim of producing an online searchable catalogue, and to undertake preservation activities, for both collections. Work started in July 2021 after our previous Wellcome Trust funded project, on the Save the Children archive, was completed. After two years we are delighted to announce the completion of the project and the launch of the collections’ online catalogues during June which will be found here.

The YMCA collection

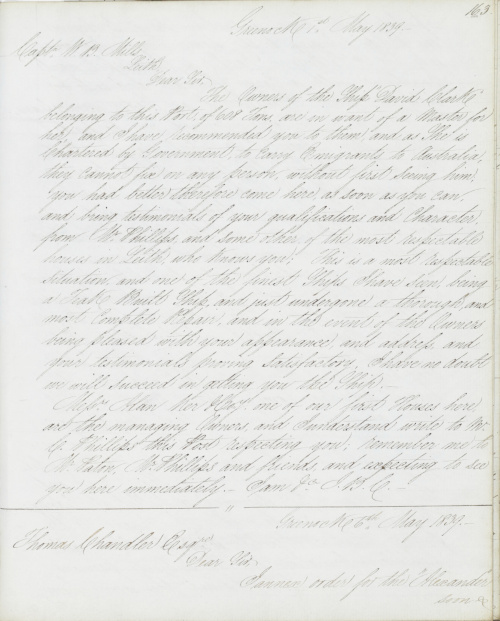

The National Council of YMCAs’ archive collection dates to the foundation of the YMCA in 1844 and continues to the 21st century covering the various facets of work undertaken during the charity’s long history. The archive primarily concerns the YMCA National Council which was formed in 1882 to support the work, and act as a national voice, of the growing network of local YMCA associations. The archive contains committee minutes and governance papers, project papers, publications and magazines, photographs and slides, and audio-visual material and objects.

The collection also contains a vast range of material regarding YMCA local associations across England, Wales, and Ireland, including prospectuses, programmes, publications, and photographs. Affiliated and associated organisations are also represented within the collection including the YMCA Women’s Auxiliary, formed at the end of the First World War, the YMCA Secretaries Association, and publications from the YMCA World Alliance.

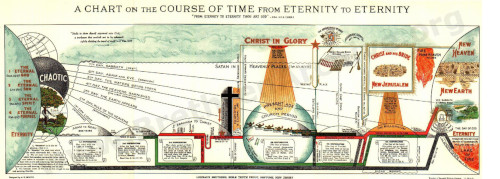

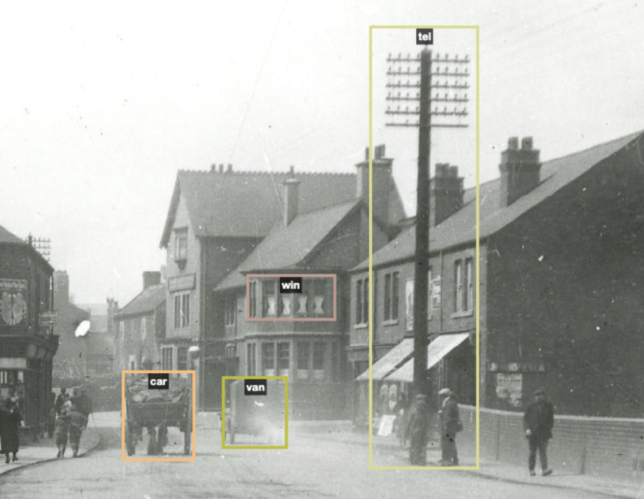

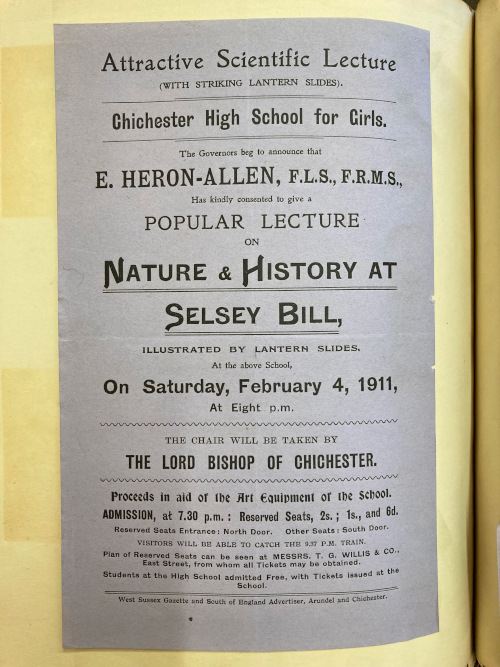

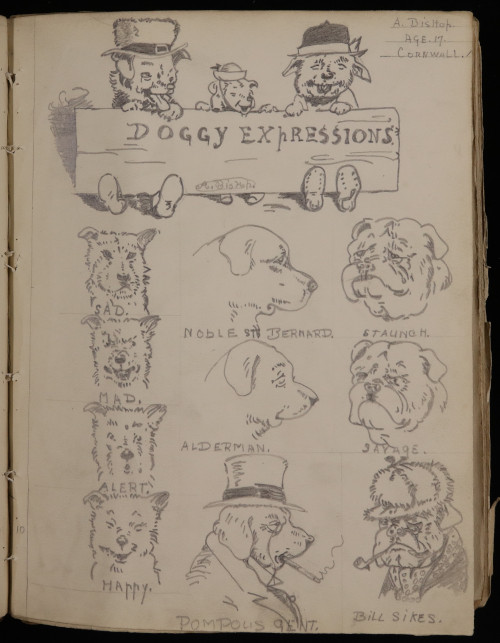

The archive documents the YMCA’s various activities to support young men’s, and later also young women’s, spiritual, mental, and physical health. Their early activities ranged from bible classes, lectures, and educational classes on history, science, and religion. Physical activity was also important with the creation of gymnasiums and sporting competitions, and in America the YMCA invented basketball. The YMCA also prioritised recreational activities and created holiday centres and hosted classes and clubs for drawings, drama, and debating. The YMCA also supported training and employment initiatives, including British Boys for British Farms’ programme, training colleges and Youth in Industry schemes.

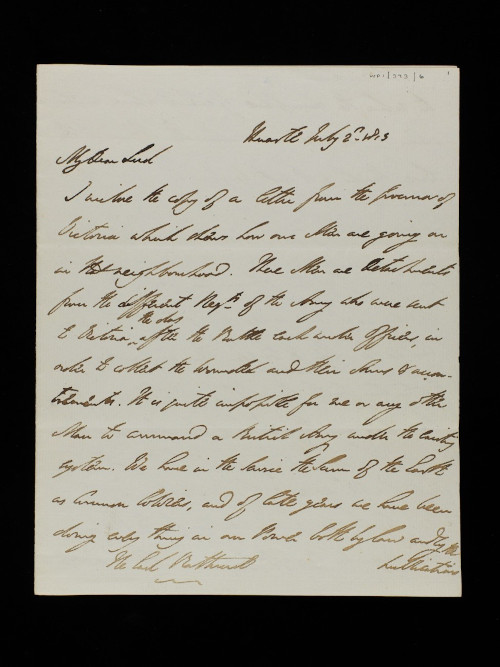

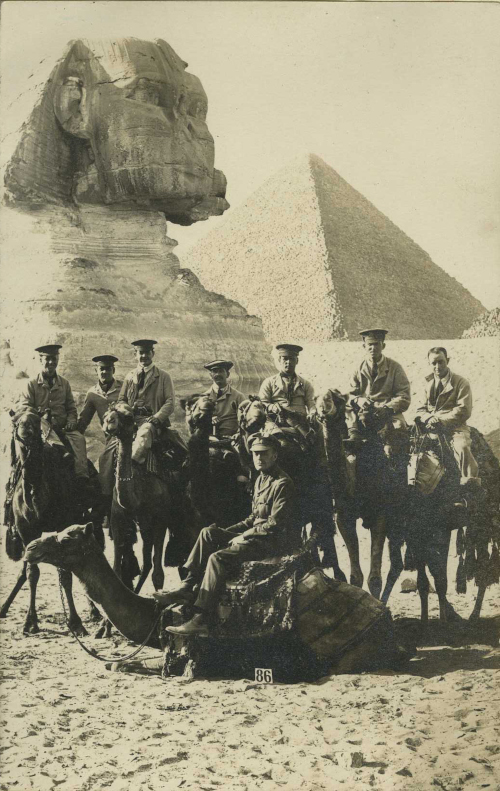

Perhaps the most well-known aspect of YMCA’s history has been their work with the armed forces, and in particular the support they provided during the First and Second World Wars. The YMCA created hundreds of canteens and huts to support the welfare needs of troops, munition workers, civilians and Prisoners of War during the First World War. The archives document this work through the ‘Green Books’ series of photographs which have been digitised and are available to view via the catalogue. During the Second World War the YMCA canteen vans were a common sight providing refreshments, including tea and cake, behind the front lines and on the Home Front during the Blitz.

The YMCA has evolved and adapted over its 179-year history to support the needs of the young people it is trying to help and today supports hundreds of thousands of children, young people, and parents every year.

The YHA collection

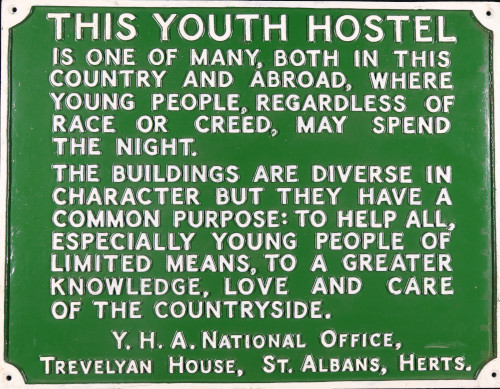

The YHA (England and Wales) was founded in 1930, following in the footsteps of the world’s first youth hostel association which was founded in Germany in 1909. The movement was set up ‘to help all, especially young people of limited means, to a greater knowledge, love and care of the countryside, particularly by providing hostels or other simple accommodation for them on their travels’. From its initial foundation, the YHA expanded rapidly. By the end of 1931, there were 73 hostels open to the 6000 members of the YHA. By 1939, membership had reached 83,000.

Although the national council and committees had overall oversight and handled high-level decision making, much of the day-to-day management of the hostels and membership fell to regional groups. The YHA archive includes national and regional governance records, including an almost complete sequence of national council and committee minutes. As well as recording the development and management of hostels and membership, these records chart YHA’s work in countryside management, outdoor education, and the development of city hostels.

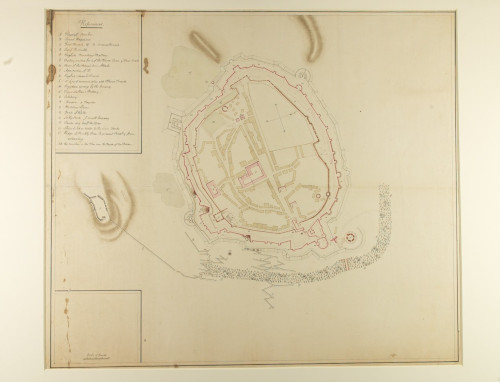

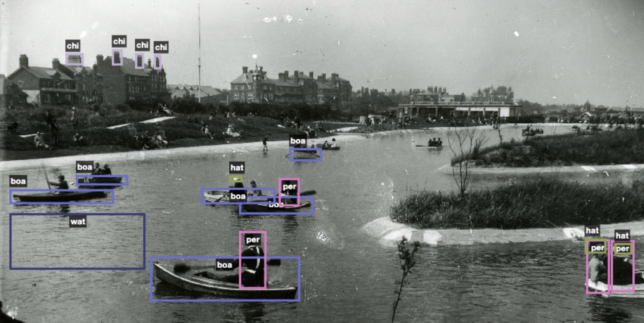

The collection also includes a large section of printed material, including YHA handbooks, guides, maps, and posters and leaflets, a large photograph collection, and property records charting the history of individual hostels, of the day-to-day management of the hostels and membership fell to regional groups.

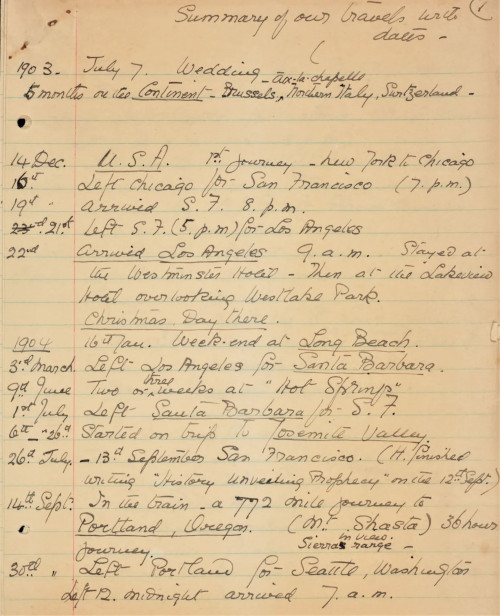

In addition to these official records, the YHA archive includes personal papers and objects collected by YHA staff, wardens, and hostellers, including diaries, hostel log books, and YHA merchandise. These records compliment the other papers in the archive and provide a more personal view of the YHA and its impact on 20th century society.

Matthew Goodwin

YMCA/YHA Project Archivist

Cadbury Research Library, University of Birmingham

Related

Archive of the YMCA (Young Men’s Christian Association), 1838-1996

YMCA Unofficial Papers: Papers of Sydney L. Vinson relating to the First and Second World Wars, early-mid 20th Century

Youth Hostels Association (England and Wales), Records of, 1929-2018

Browse all Cadbury Research Library, University of Birmingham descriptions on Archives Hub.

Previous Archives Hub features on the Cadbury Research Library, University of Birmingham collections:

Comic strips and seaside holidays: unexpected stories from the Save the Children Archive

All images copyright Cadbury Research Library, University of Birmingham. Reproduced with the kind permission of the copyright holders.