Beginnings

The story of Conway Hall Ethical Society dates back to 1787 and a nonconformist congregation, led by Elhanan Winchester, rebelling against the doctrine of eternal damnation. This group of freethinking individuals, based in a small chapel on the eastern edge of London (Parliament Court Chapel), was the beginnings of what was to become a society of radicals and social and political reformers, devoted to freethought. There is no other Society in the United Kingdom, possibly the globe, that has such a long history dedicated to creating a fairer, more equal world through free religious thought and ethical enquiry.

It has had many names, being known as the Philadelphians (or Loving Brothers), Universalists, Society of Religious Dissenters, South Place Unitarian Society, South Place Society, Free Religious Society, South Place Religious Society, South Place Ethical Society and now Conway Hall Ethical Society.

Throughout its early history as a religious institution, the Society’s ministers led the congregation through various spiritual quandaries, including the rejection of the Trinity, which lost the Society many of its members. It weathered the loss, however, surviving and flourishing after many similar erosions of membership on the progressive journey from universalism and unitarianism to the present humanist position, which the Society had reached by the end of the nineteenth century.

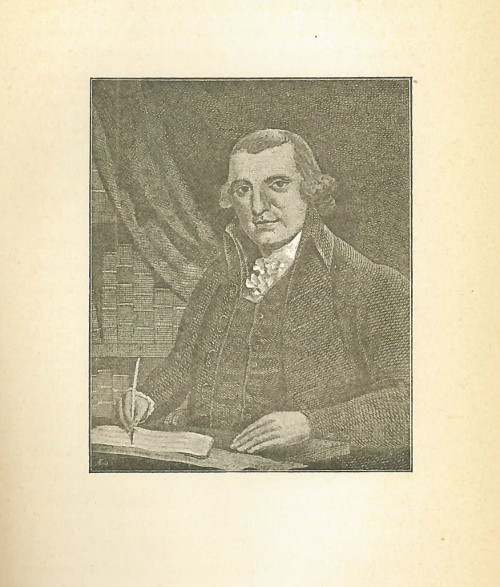

William Johnson Fox (1786 – 1864)

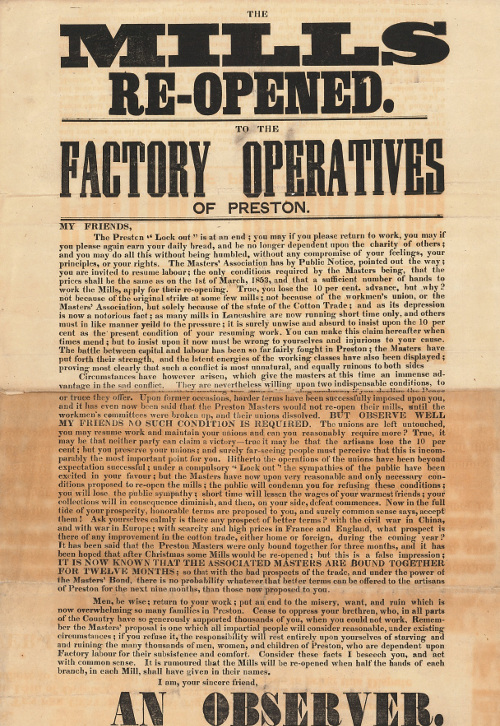

Notable leaders of the Society include renowned orator William Johnson Fox who became minister in 1817. His popularity, resulting in an increase in the congregation, led to the construction of their first purpose built home, South Place Chapel in Finsbury, into which the congregation moved in 1824. Among the congregation and its close kin was a circle of radicals and progressive thinkers who stood for various political and social causes, including women’s rights, suffrage and education for all. These included women’s rights advocates Sophia Dobson Collet and Caroline Ashurst Stansfield, poet Robert Browning, philosopher John Stuart Mill, social theorist Harriet Martineau as well as adherents of William Lovett and Chartism.

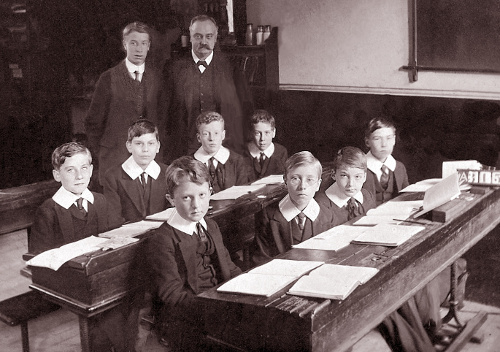

Fox himself was an early supporter of women’s rights, campaigning in regard for women’s rights respecting infant custody, marriage and divorce and for freedom of the press. He was also a Member of Parliament where he was renowned for his impassioned speeches against the Corn Laws and stringent support of the Lancastrian system of education, which ultimately resulted in the opening of board schools and free education.

Fox remained minister until 1853 during which time he led the congregation toward a more rationalist outlook reflecting the freethinking nature of both himself and the circle of intellectuals that surrounded him both within and without the congregation.

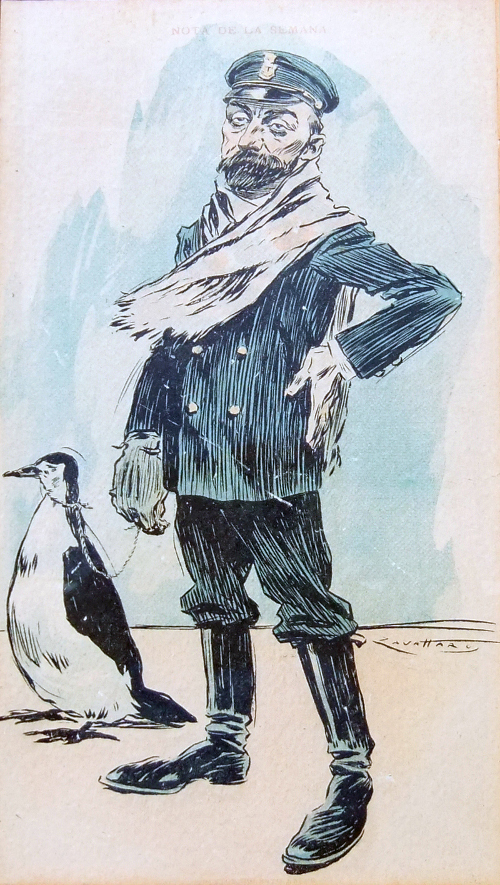

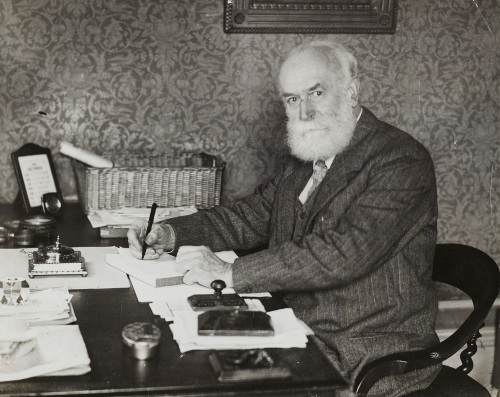

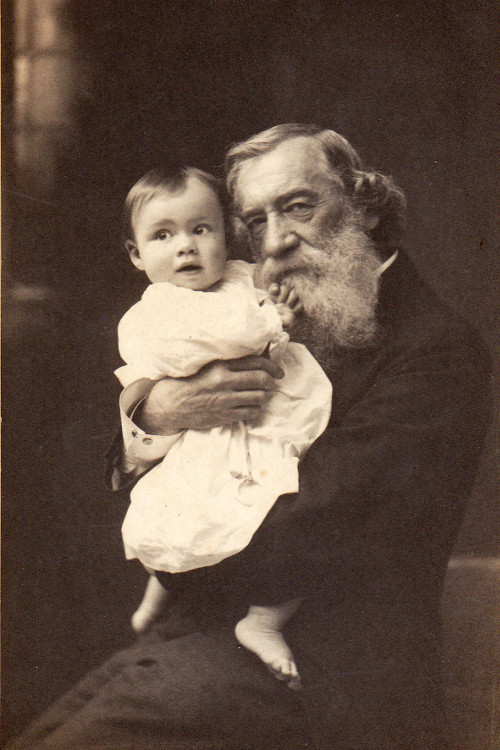

Dr. Moncure Conway (1832 – 1907)

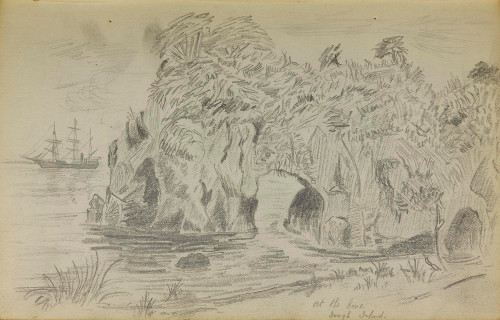

The most outstanding of Fox’s successors was an American, Moncure Conway, after whom the Society‘s present home is named. He settled at the South Place Chapel from 1864 until 1897, excepting a break from 1885 to 1892 during which he returned to America and wrote his famous biography of Thomas Paine. Conway had adopted an uncompromising anti-slavery position at home, despite having two brothers serving in the Confederate army, and came to England in 1863 on a speaking tour. The same year he helped his father’s slaves escape to freedom in Virginia at the start of the American Civil War.

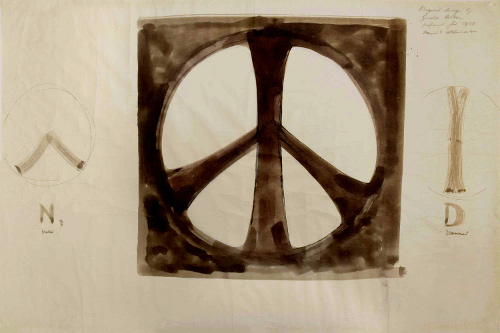

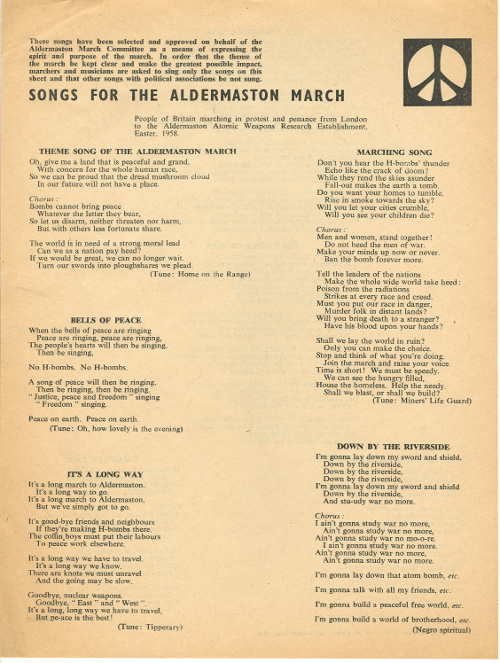

He was also a supporter of women’s rights, speaking at the first recorded public meeting on women’s suffrage in 1871 at Hackney Town Hall and he was strongly anti-war. These pacifist beliefs being cemented during his experience of seeing first hand the brutality and devastation of battle whilst a war correspondent during the Franco-Prussian war.

His views seem to have been formed by his questioning outlook and by the intellectual circles he inhabited which included the likes of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Walt Whitman, Mark Twain and Louisa May Alcott in America and George Eliot, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Charles Dickens and Charles Darwin in London.

The breadth of his interests is reflected in the discourses he gave which covered such matters as slavery, religion, war, ethics and freedom of expression. It is Conway’s unquenchable curiosity about the world around him and the religion that had been his calling that was ultimately responsible for taking his rationally minded congregation towards its current humanist approach and which in 1888, under the leadership of Stanton Coit (during the seven year break of Conway’s tenure), finally lost its remaining religious trappings cemented in the change of its name from South Place Religious Society to the South Place Ethical Society.

Conway Hall

Conway Hall, and our previous home South Place Chapel, have witnessed many of the great and the good from the world of radical and liberal thinkers, including political activists such as Annie Besant, Charles Bradlaugh and Peter Kropotkin, suffragettes Marion Phillips and Marion Holmes, writers T. H. Huxley, Charles Darwin, William Morris, H. G. Wells, Dora Russell, Bertrand Russell and in more recent times Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens, Brian Cox and Jacqueline Wilson.

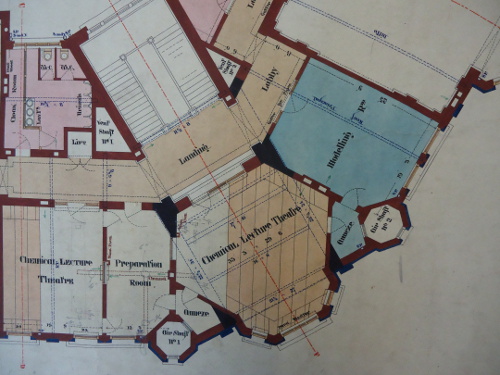

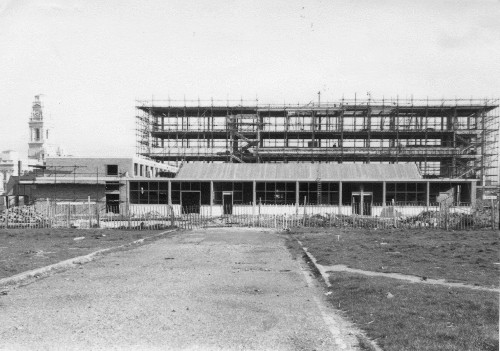

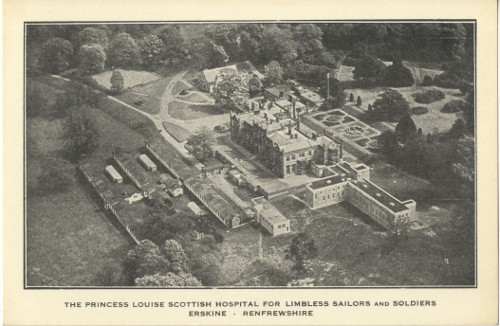

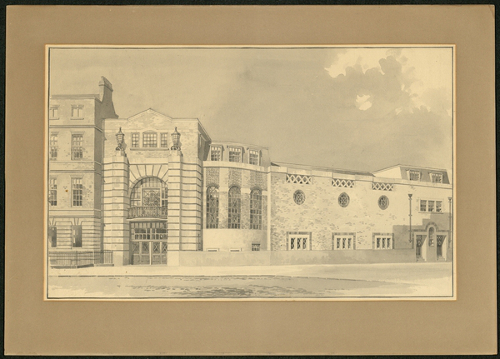

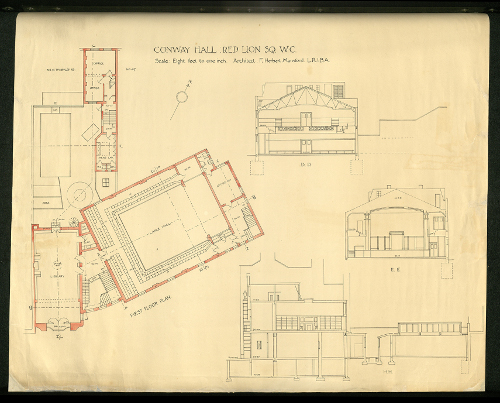

The story of our current headquarters, named after Moncure Conway, dates back to the beginning of the last century. By 1900 the Society realised its current home in South Place was no longer fit for purpose, and began debating whether to repair the existing building or investigate erecting a new one, potentially on the same site. At this early stage plans were drawn up by architect Frederick Herbert Mansford F.R.I.B.A. (1871–1946) for a new home. Mansford, along with his three siblings, had been a lifelong member of the Society. His brother, Wallis, advocated selling the Chapel and erecting a new building which would have a ‘swimming bath convertible into a gymnasium in winter months,’ a bookshop, separate lending and reference libraries, a labour and emigration bureau and a roof garden. Sadly, progress was halted by the outbreak of the First World War, but money raised from the sale of South Place Chapel in 1921 along with an appeal for funds finally allowed the construction of Conway Hall in 1928. F. Herbert Mansford was appointed architect.

The new building was to be a place of enlightened education and social activity, and was designed with this in mind. Whilst funds did not allow for the extent of Wallis Mansford’s wishlist, his brother worked with the building committee to create an edifice with space to hold lectures, concerts, dances, social evenings and play-readings as well as a library and spaces for the various membership groups, such as the Ramblers’ Club and the Poetry Circle. The new headquarters for South Place Ethical Society opened officially on 23 September 1929.

The Society today

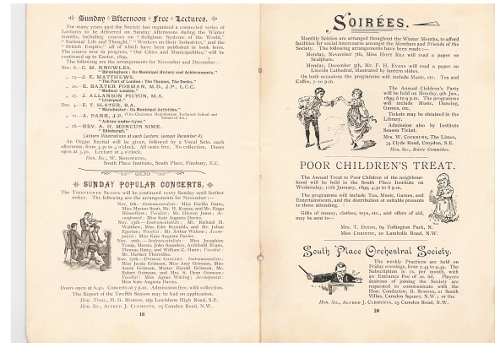

Today, the Society is an educational charity whose objective is the advancement of study, research and education in humanist ethical principles. Conway Hall offers a vibrant range of cultural activities including classical concerts (the longest running chamber-music series in the world), exhibitions, contemporary dance and theatre as well as free access to our Humanist Library and Archives. Through the Library and Archives we run a variety of learning activities (https://conwayhall.org.uk/learning-at-conway-hall/). These include adult education courses, talks and debates, family activities and sessions for schools covering a range of subjects linked to the heritage and ethos of our Society.

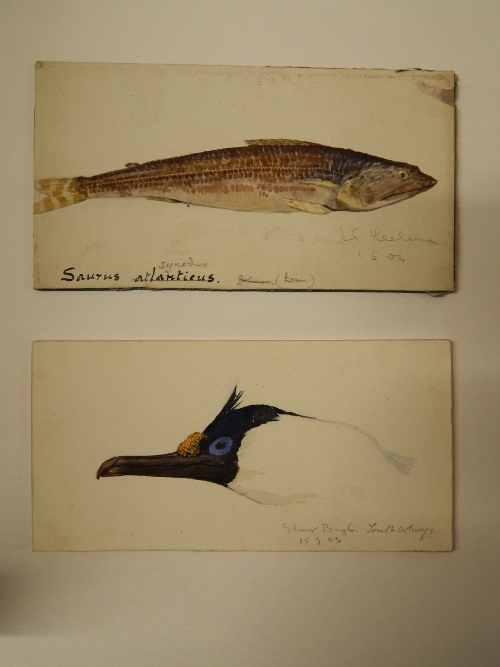

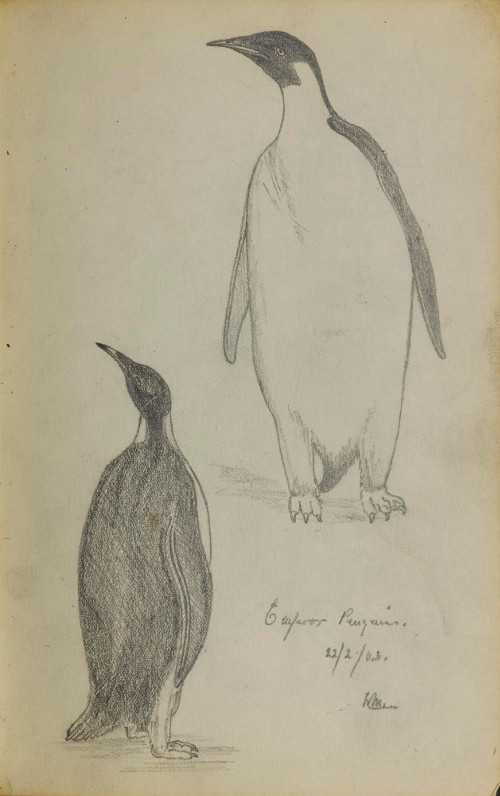

Conway Hall Humanist Library and Archives

The Library and Archives was founded in 1886 at a time when public libraries were a rarity in the U.K. and when self education was being promoted for those without the means to access education. Free access to knowledge through books and pamphlets was seen to be the foundations of our Society which led to the creation of the Society’s free library, with a special section for children.

Today the Library houses a humanist collection covering such subjects as ethics, philosophy, free speech, education, environmental issues, civil rights, animal rights, religion and rationalism and holds rare and important journals such as The Freethinker, The National Reformer, The Republican, The Agnostic Journal, The Literary Guide and our own journal, The Ethical Record.

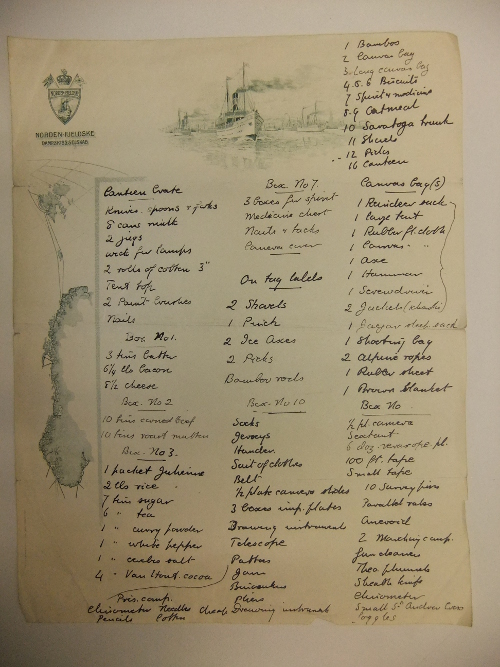

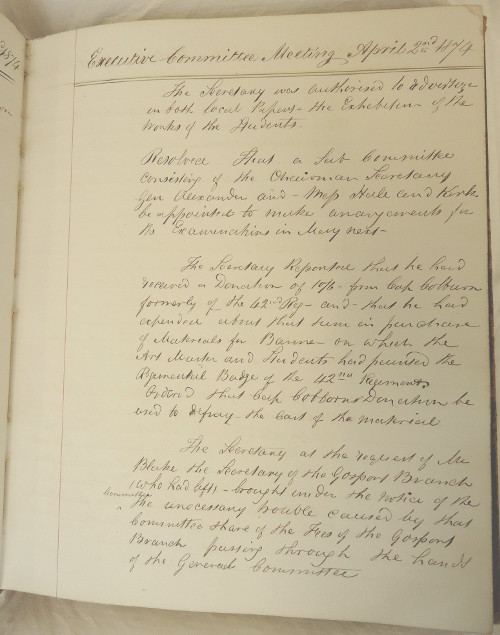

We hold the archives of Conway Hall Ethical Society which record our Society’s evolution from the radical dissenting congregation of the 1790s, through the nineteenth century challenges to thought and belief, to the creation of Conway Hall in the 1920s and the educational charity of today.

We also hold the archives of the National Secular Society from 1875, a campaigning organisation promoting secularism established in 1866 under the leadership of Charles Bradlaugh.

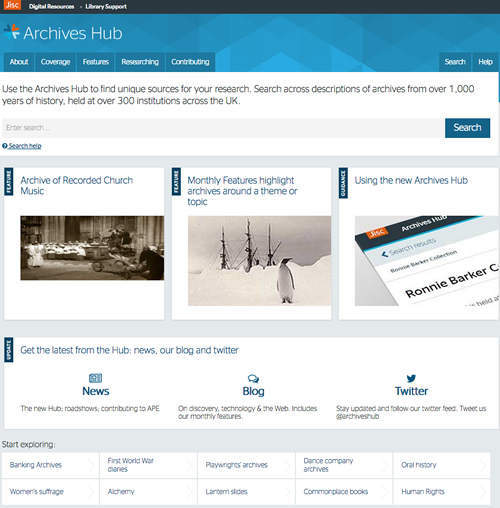

Among our collections we have treasures such as the manuscript autobiography of the Chartist leader William Lovett (1800–1877), Illuminated addresses presented to Charles Bradlaugh (1833–1891) and artefacts such as Richard Carlile’s (1790-1843) prison writing desk. You can search our collections here (https://conwayhall.org.uk/library/search-the-catalogue/)

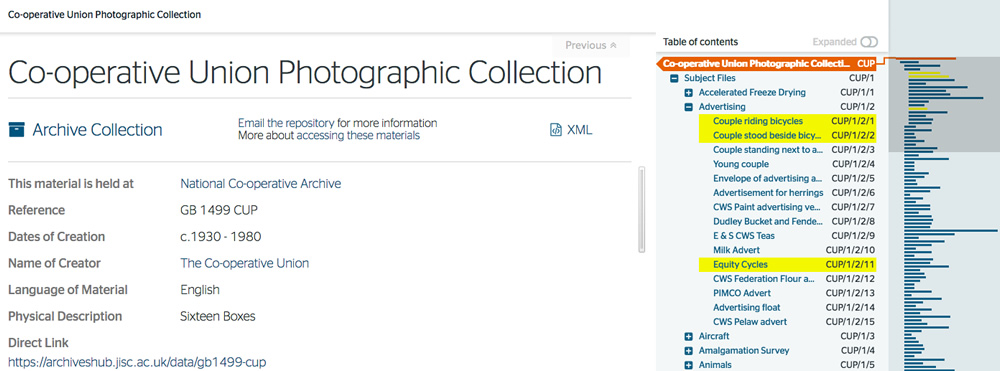

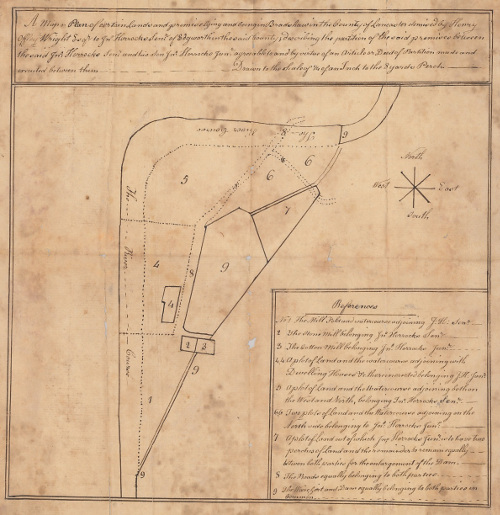

Since 2015 we have begun the intricate task of digitising our collections. You can explore the pilot project, Architecture and Place, here (http://conwayhallcollections.omeka.net/). It has allowed us to digitise items relating to our current and former homes such as plans, leases and photographs and you will also find the files documenting the plans and procedures we have put in place for our future digitisation projects. We hope these will be useful for other organisations working on small budgets and with small teams.

Sophie Hawkey-Edwards

Library and Learning Manager

Conway Hall Humanist Library and Archives

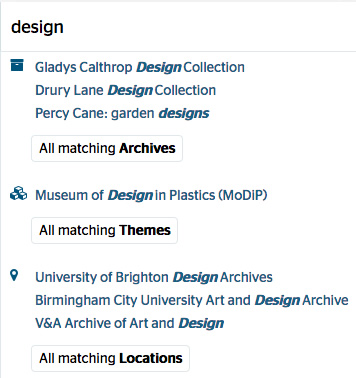

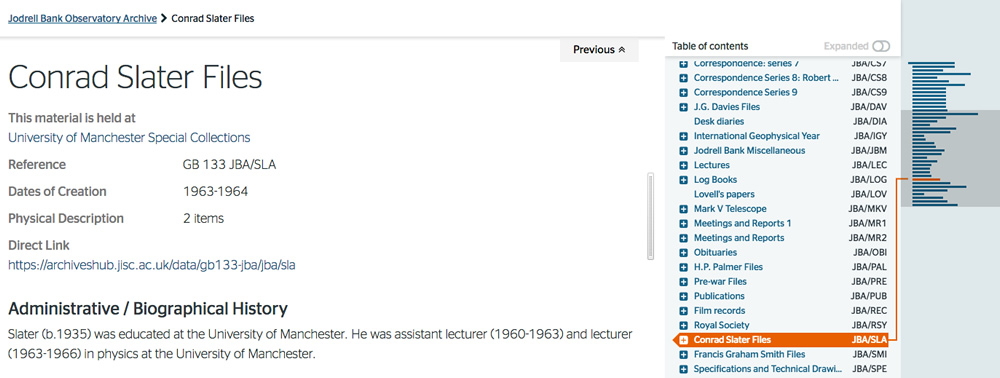

Explore Conway Hall Humanist Library and Archives collections on the Archives Hub:

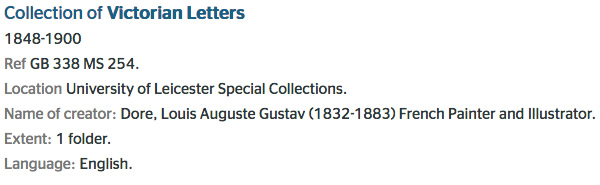

Harold Blackham Archive, 1919-2009

Red Lion Square deeds, 1685-1968

Also on the Archives Hub

Subject search: Humanism

Correspondence of William Johnson Fox, 1831-1847 – part of the Robert Owen Collection at the National Co-operative Archive.

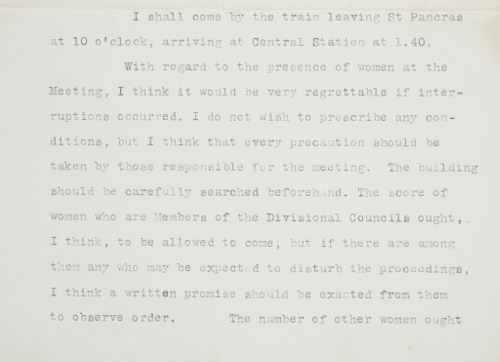

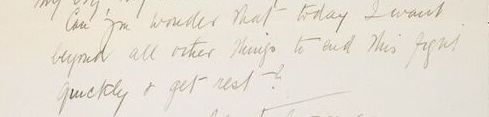

Letters from Moncure Daniel Conway, 1880s – part of the Spence Watson/Weiss Papers at Newcastle University Special Collections:

Letter from Moncure Daniel Conway to Elizabeth Spence Watson, c.1880s

Letter from Moncure Daniel Conway to Robert Spence Watson, 1885

Letter from Moncure Daniel Conway to Elizabeth Spence Watson, 1883

All images copyright Conway Hall Ethical Society and reproduced with the kind permission of the copyright holder.