Consider the following questions, which use the topic of design history, but could be for any topic area:

Where did this person work?

Who did they know?

What can I find out about furniture design in London in the early 20th century?

Who designed this early 20th century chair?

Did the designer feature in this exhibition?

Can I find photographs of this section of the exhibition?

Did these designers both feature in this design exhibition?

Who influenced this designer?

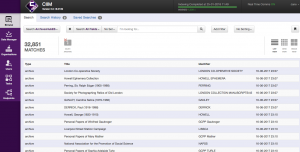

These are surely typical questions for researchers. They are the sort of questions we thought about when we were working on Exploring British Design. But these questions do not start with the archive. An archive collection may well hold many answers for these questions, but there remains the problem of connecting these questions to the archive: ‘I’m interested in this designer/in this chair that they designed/in this exhibition they designed for’. We need these questions to lead to archival sources when appropriate.

Which comes first, the research question or the archive? We tend to assume the archive, but for many researchers the question comes first and the archive is, at that point, not known to them. We become a little fish in a very big pond when we enter the Web, and so we need to find ways for researchers who may not be aware of us to hook our collections.

Wellcome Library, London: Fishing

Wellcome Library, London: Fishing

But how do we achieve this? We often have to work within considerable constraints and we cannot simply transform our cataloguing practices. There are many technical solutions that we can potentially make use of, but I think the first challenge lies with the data itself.

Individual archive repositories may think that there is no way they can move into a Linked Data world of RDF and triples and persistent URIs. But I think there are steps that we could take to help our descriptive data better fit this kind of landscape and have the potential to be more ‘linked in’ to other sources and to researchers’ paths of discovery.

Our descriptive practices tend to treat collections as stand-alone entities, rather than integrated parts of a whole information landscape. We do not think enough about cataloguing in a way that facilitates an integrated approach where we can connect to other information resource and allow researchers to come to archives through searching for people, organisations, subjects, events and places, and to come to them as part of a whole network of resources. I think we need to try to think about providing potential ‘connectors’ within our descriptions that will allow them to be hooked into the landscape more effectively.

Here are some thoughts about how we can help to achieve this:

Be consistent when cataloguing

This may sound straightforward, but having looked at thousands of descriptions from well over two hundred archive repositories, I can announce that it doesn’t always happen. For instance, simply entering the name of the repository in the same way for every catalogue entry, and not adding the repository code as part of the repository name, for example, ensures that the repository is always correctly identified. This means that all of the collection descriptions can be clearly identified as being from the same institution.

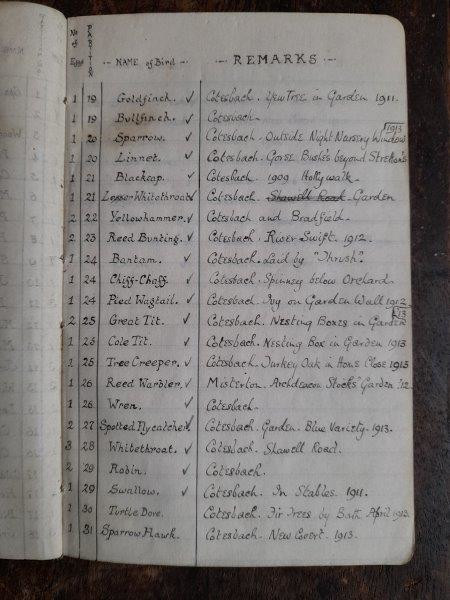

When entering names, think about how you structure them. Many archive systems provide a means to store and link to names, and yet it is amazing how often one name varies. If nothing else, think about adding life dates to a name, which helps with unique identification.

Here on the Archives Hub we have to hold our hands up for a potentially unhelpful practice up till now of encouraging the creator name to be entered in one way under ‘name of creator’ and another way as an index term. This reflects a time when we were less focussed on machine processing. Of course, it is much better to enter the name consistently, so that the connection can clearly be made.

Try to use rules and standards

Whilst I have increasingly become somewhat frustrated by our standards, I still think there is a role for standards to encourage consistency, clarify meaning and help draw things together. If you enter subjects using UKAT or LCSH, then try to ensure that all your terms really do come from these thesauri. We get examples where the thesaurus is named, but the subject is not actually from the thesaurus.

When entering things like language codes (ISO standard 639), take a few minutes just to find out about them. They need to be lower case, to be consistent. It’s worth having an understanding of what you are doing and why.

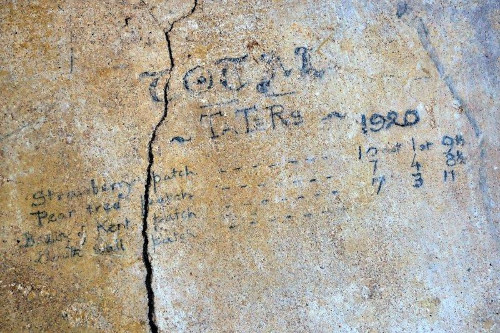

Do the same for dates. Think about what a normalised date is and why it is important. It is really worth having a sense of why these things matter. ISO8601: “The purpose of this standard is to provide an unambiguous and well-defined method of representing dates and times”. That sounds perfect for archives, and well worth adopting.

Think about the questions people ask

One of the advantages of indexing is that it gives you a chance to consider the terms you can best use to ‘advertise’ your collection. It is really good to if the scope and content text is clearly reflected in the index terms. If your archive is about a designer and you have described things they have designed, then you might realise that you haven’t used ‘furniture designer’ in your text, but this is a good index term to use. Or maybe the archive is really useful for those looking at the history of design education, but you haven’t yet actually used the term ‘design education’ in your text. You can add it as an index term.

Try to think beyond the UK

This may again sound obvious, but unfortunately NCA Rules don’t exactly encourage this, even if they don’t prevent it. When indexing by place name, add the county and certainly add the country. Indexing really helps us think about this. Consider a typical biographical history entry:

Charles Edward Sayle was born in Cambridge on 6 December 1864. He entered New College, Oxford, in 1883, and St John’s College, Cambridge, in 1890.

It wouldn’t look quite right putting:

Charles Edward Sayle was born in Cambridge, England, on 6 December 1864. He entered New College, Oxford, England, in 1883, and St John’s College, Cambridge, England, in 1890 [etc]

And whilst it would help with identification, it is still unstructured. Much better to ensure you have:

Place name: Cambridge, England

in your structured index terms. True, there are plenty of ways to mark this up, some better than others, but at least having an index term entered in this way is a great help with uniquely identifying the Cambridge that you mean, as opposed to the one in the US or New Zealand, Australia or Jamaica. It means that a researcher who is researching a topic around ‘Cambridge, England’ is more likely to find your description.

If you put your place names into some kind of specific field, try to avoid something like ‘Cardiff, Merthyr Tydfil, Cambridge’ (an example from the Hub) or ‘Cambridge etc’ (another example). So if your cataloguing software provides just one box for place, repeat that box for each place, rather than putting a load of them into one entry. If it allows for something like place name and country, use that to your advantage.

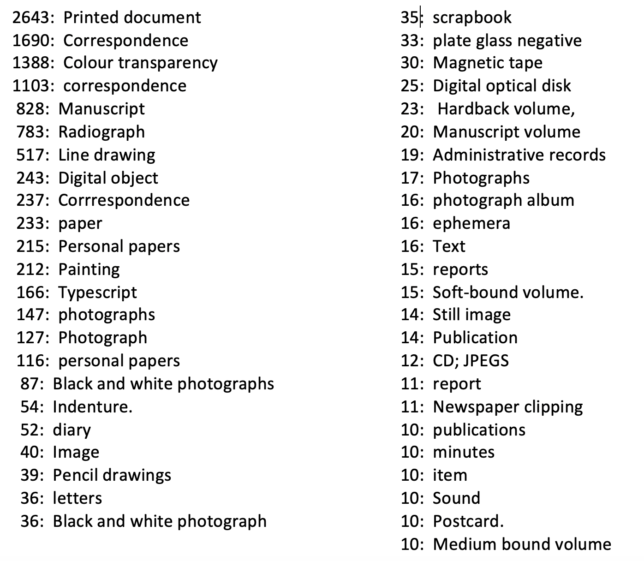

Put index terms into the most appropriate categories

On the Hub we’ve had plenty of family names as personal names and personal names as corporate names. But most commonly we get genre as subject. If your archive contains photographs, press cuttings, preliminary sketches or parchment (animal material) and you want to make this known, you need to index by material type, not by subject ….unless the archive is about photographs or about parchment.

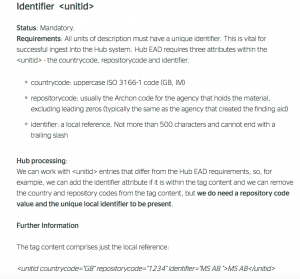

Think Reference!

Your references should give the ability to uniquely identifying every part of a hierarchical archival description. Think carefully about adding them and make sure you have a unique reference at every level of description. Some archival software will automatically generate references, which does help because then they will be consistent and unique. But if you add them manually, it is very easy to make a mistake. On the Hub we found several hundred duplicated ‘unique references’ when we went through a major exercise to clean up references. And I do mean several hundred, not one or two.

Optimise titles for search engines

All of this structured data really needs the boost of descriptions that work well on the Web, simply in terms of being discoverable. SEO, or search engine optimisation, is a big topic, and your system may not allow you to make many changes, but in terms of the actual data, do think about appropriate titles, which are a really good hook. Include the most significant words, make sure that are not too long (so they are easy to scan for a researcher looking through various sources) and make titles at collection level self-explanatory. At lower levels this is not such a problem, as it is possible to append the collection title, to help with interpretation.

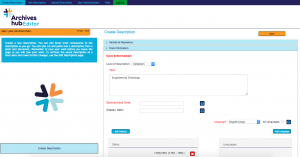

Look at how your data exports

This may not be possible or practical for everyone, but if you can do it I think it is a really good indicator of how interoperable your data might be to see how it looks when it is exported, because that is when you are removing it from the comfort of your own familiar system, and potentially unleashing it into the world.

The Event Horizon

I am particularly interested at the moment in events. History is made up of events. Who’d have thought it, when our standards barely mention them!

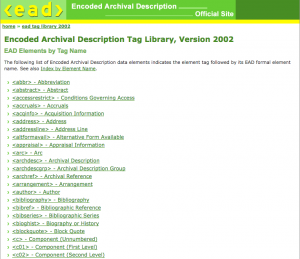

EAD (Encoded Archival Description), our XML standard for descriptions, doesn’t allow for events to be indexed at all. CIDOC CRM is “a formal structure for describing the implicit and explicit concepts and relationships used in cultural heritage documentation” and it is event-based. It may be a complicated beast, not much used within our domain, and many of you won’t be aware of it, but there is certainly something to be said for putting events at the forefront of how we think.

The new EAC-CPF standard allows for chronologies in the biographical section of the description, but this is more about narrative (a list of events as part of one name authority description). It is based partly on ISAAR(CPF) which states “Record in narrative form or as a chronology the main life events, activities, achievements and/or roles of the entity being described.” Narrative form is fine for a researcher who is perusing the description, but structured form that is not necessarily so closely tied to narrative is what is required for more integration of data.

People, organisations, places and subjects are all linked by events – that is where the connections and the stories are. I think it is a major shortcoming of our standards that events are not given more prominence.

I mention this here really just to say that whilst we can improve our descriptions, and think about consistency and indexing, I do think that there are things around cataloguing that may require a more fundamental change.

Research Questions

Coming back to the initial questions I asked. Our cataloguing can help to ensure that archives are networked in to the broader information landscape. This is not about whether the archive can in principle answer these questions. It is about whether a researcher asking these questions (maybe initially through Google, maybe through other generic channels) can discover the archive as one source amongst many:

Where did this person work?

Uniquely identify the place(s).

Who did they know?

Make sure names are consistent and try to make them unambiguous.

What can I find out about furniture design in London in the early 20th century?

Use appropriate index terms and think about how to add dates consistently.

Who designed this early 20th century chair?

Adding index terms helps to draw out significant names and concepts

Did the designer feature in this exhibition?

Entering the exhibition name and designer name as structured data will help.

Can I find photographs of this section of the exhibition?

Make sure you have the exhibition name clearly stated and think about using index terms for formats – these are a great means for researchers to find types of material. But remember, this is ‘photographs’ as a genre or form, not as a subject!

Did these designers both feature in this design exhibition?

Not so easy, as we don’t index by event type

Who influenced this designer?

Not so easy, as we don’t tend to provide structured relationship information to connect people other than in the broadest possible way (these two people were ‘associated’). But that is another story…

To my mind, cataloguing is a skill, and it is really worth thinking about what you are cataloguing and how you catalogue it carefully. It is more important to think about this now than it was 30 years ago, because 30 years ago we were working with with narrative descriptions and index cards. Now we want our data to be interconnected.