At a very productive and enjoyable workshop last week we brought Archives Hub contributors and others interested in the future development of the Hub together with members of our Steering Committee. Our aim was to generate discussion around some key topics that we think are particularly important at the moment, and relevant to how the Hub grows and develops.

1. Open Data

Our first discussion was around the open data agenda, something that is becoming increasingly relevant as we move towards new ways of outputting and inter-connecting data. We are particularly interested in this because of our current work on the Locah project (Linked Open Copac and Archives Hub). We had a group discussion around factors that may act as resistors and those that may act as drivers for open data (points are reproduced here as accurately as possible from the group discussion):

Resistors

– Problem of providence/attribution

– Is it just a fad?

– Loose control of metadata

– Potential de-skill

– Create demand or expectations you cannot meet

– May create resourcing problems

– Manipulation of the data by others could reflect back badly on the institution

– Brand/impact – ‘stamp’ is potentially lost (need to show impact often relates to funding)

– Depositor relations could be an issue – what are their expectations?

– Impact/ benefit is difficult to track and measure

– Difficult to explain the benfits to get buy-in

– Cultural shift away from concept of whole collection? [acknowledgment this could require a radical change in mindset]

Drivers

– Linked data connections can be made

– Political drivers – Government agenda

– Opportunities may be missed

– Without innovation we risk reinforcing the ‘dusty’ reputation of archives/archivists

– Transparency & FOI

– Users want to make their own connections within datasets

– May help free us from constraints

– We are sharing anyway

– Increases discoverability

– Opportunities for more collaboration

– Can take advantage of innovations by others

– As a profession we can show that we produce quality metadata

– No pure form of metadata anyway

The feeling was that open data is probably the way to go, but there were some reservations. Probably the main ones that were emphasised were (1) the lack of control over the metadata that might lead to it being used in ways that reflect badly upon the institution, and (2) the problem of measuring impact once you relinquish control – it is hard enough when the data is essentially within your control. There were some interesting points made around things like user expectations and the dangers of raising expectations and not being able to meet them. I think that this referred to the need to maintain an open agenda once you have embarked upon that road. One point that I hadn’t fully considered was the attitude of depositors – some depositors may not be keen to see descriptions of their collections being released in this way. This brought us back to the need to make a compelling case and show how it could benefit the profile and use of archives.

The group discussed the difficulties around getting buy-in, and it was felt that more exemplars and applications were needed: ways to really show the benefits of open data in a way that funders and managers could understand. We also raised the whole issue of the change in mindset that may be needed here, particularly with Linked Data, where you are moving away from the archival collection as the main emphasis and towards data from different sources that is inter-connected and presented to the user in a myriad of ways (appropriate for their needs).

2. Remit

Here we had a general discussion and made points around the remit of the Hub in terms of the archives that are represented. The discussion also ranged more widely, around how the archive community should be developing and the role of the Hub more generally.

– Hub funded for HE but acknowledgment we want to expand user base

– It is not an either/or scenario – we can represent all archives

– Search across various aggregators has never been achieved

– As a community we don’t present totality well – we still seem fragmented

– We should think beyond the UK – researchers often want this

– Many archive repositories will see higher Google ranking as incentive for being on the Hub

– Stereotype of historians may not be positive: we should think more broadly

– Recognition of ‘Old school’ research methods versus new methods – Hub could have role in exploring this – research habits & cultural shift – how does this affect archives?

– Hub can help accelerate inter-disciplinary research using archives

– UKAD could have a role looking at the profile of current archival networks

– The Hub is an ac.uk address – does this have an impact on perceptions of it as being only for HE?

– Hub could help with the current trend towards digitisation on demand – this could be functionality within the Hub (user requests digital copy)

– Worth thinking about getting data from sources like Microsoft Excel and maybe helping with guidelines for cataloguing in Excel

– Could the Hub cover more than EAD descriptions, e.g. PDFs?

– Could the Hub include ISDIAH based descriptions as a means to give archive repositories at least a ‘placeholder’ presence?

We generally agreed that a broader remit is a good thing, and there was support for us approaching community archives to see whether we can represent them. But we did agree that, despite progress in terms of the existence of a number of aggregators in the UK and beyond, we don’t present the totality of archives very effectively – maybe we still need to make more effort to work together on this.

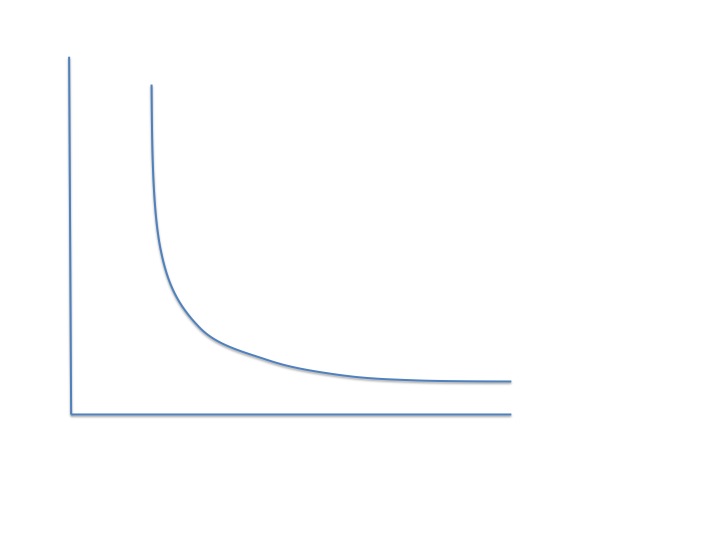

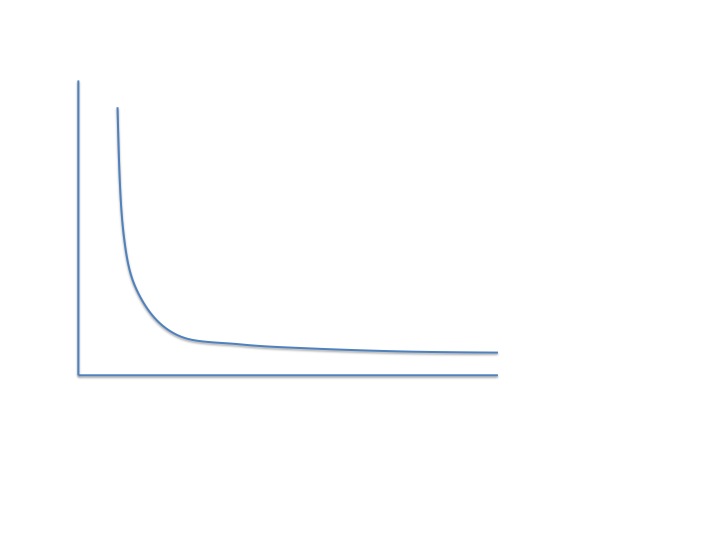

3. Priority Areas

In the afternoon, at our Steering Committee meeting, we asked members to rank priority areas, which we gave as:

- Increase usage

- Increase coverage/ depth of content

- Innovation

- Technical development (core service infrastructure)

One member wanted an additional priority area:

- Understand our audience better

The interesting thing about this discussion was that we had a spread across all of these areas, but the ways that they are reliant on each other really became obvious. Some members felt that if you concentrate on increased coverage, increased use would follow. Others saw it the other way around. Some felt that innovation would help to place you at the forefront of the community and attract more profile, more contributors and more users. It was felt that ‘technical development’ went hand-in-hand with innovation.