Archival descriptions need to include associated subjects, names and places as index terms. Is that self-evident? Well, certainly we need to do what we can to provide ways into an archive, and you might say the more ways to access it the better. But do archival descriptions need index terms? Do they add anything that keyword searches don’t have?

Archival descriptions need to include associated subjects, names and places as index terms. Is that self-evident? Well, certainly we need to do what we can to provide ways into an archive, and you might say the more ways to access it the better. But do archival descriptions need index terms? Do they add anything that keyword searches don’t have?

The Archives Hub encourage our contributors to add access points, which is EAD speak for index terms for subjects, names and places that reflect the content of the description, and therefore the archive. But if those terms are already included in the description, with the technology at our disposal, maybe we can dispense with them as access points and simply query the main body of the description? What are the arguments in favour of keeping index terms?

1. It’s about what is significant. One of the great challenges with archives is drawing out what is important within the archive; enabling researchers to know whether the archive is relevant to them. But this is always going to be a very imperfect exercise. I remember cataloguing an architect’s diaries (Robert Mylne, architect of Blackfriars Bridge) and ending up taking months because I couldn’t bear to leave out any people, or place names or buildings, or building techniques, etc. What if someone really wanted to know about stanchions? If I didn’t mention them, then a search would not bring back the Mylne diaries, and I would have failed to connect researcher to research material. The reality is that with the time and resources at our disposal, what we need to try do is reflect what is ‘most significant’ and include ‘key concepts’, accepting that this is a somewhat subjective judgement and hoping that this is enough to lead the researcher in the right direction. For the Hub we usually recommend adding somewhere between 3 and 10 index terms to a description. It means that the archivist can (arguably) draw out the most pertinent subjects and list the most significant people.

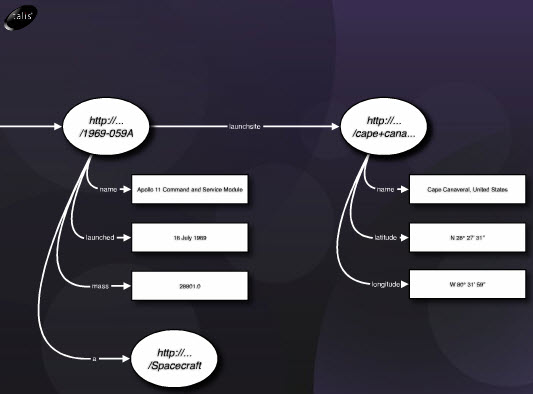

2. It allows for drawing out entities. So, in a sentence like “The collection comprises of material relating to the British National Antarctic Expedition, 1901-1904 (leader Robert Falcon Scott), the British Antarctic Expedition, 1907-1909, led by Shackleton, correspondence with his family, miscellaneous papers and biographical information”, you can separate out the entities. Corporate bodies such as British National Antarctic Expedition, 1901-1904, and personal names such as Robert Falcon Scott. This is very useful for machine processing of content, as machines do not know that Robert Falcon Scott is a personal name (although we are increaingly developing sophisticated text mining techniques to address this).

It can be particularly useful where the entities are not obvious from the text, such as “[A]s well as material relating to his broadcast and published works, the archive also includes many scripts…”. Notice a lack of definite subject terms such as ‘playwright’, or ‘writer’. A human user may infer this, but a general search on ‘playwright’ will not bring back any results becauase a machine has to know it too, in order to serve the human user.

3. You can then apply consistency to the entities, in terms of using a pre-defined controlled vocabulary. Bu in a world where folksonomies are becoming increasingly popular, with increasing use of user tagging, does it make sense to insist on controlled vocabularies?

Take the example above, which is about Arthur Hopcraft. The index terms do include ‘playwrights’ and ‘writers’ so that the user can do a keyword search on these terms, or a specific subject search, and find the description. However, there is an obvious flaw here: the archivist has chosen these terms. Whilst they do both come from the Unesco thesaurus, she could easily have chosen different terms. The index terms do not include ‘scriptwriter’ for example. They do not include ‘television’ or ‘journalism’, both of which could have reasonably been used for this description. We end up with some descriptions that use ‘playwrights’ as a controlled vocabulary term, but others that don’t, and some that maybe use ‘scriptwriters’ when they are essentially about the same subject, or ‘authors’ which is the Unesco preferred term for scriptwriters.

But you cannot cover everything, so you have to make a choice about which subject terms to use. The question is: is it better to have some subject terms rather than none, even if they do not necessarily cover ‘all’ subjects, and so the researcher may carry out a subject search and not find the archive? One important point is that with our without subject terms, you have the same problem; it is just that a specific subject search does actually narrow what the researcher is searching on – the search may not include other fields, such as the scope & content or biographical history. Therefore whilst a subject search helps the researcher to find the most significant collections, it may exclude some collections that might be very pertinent for their research (collections that they may find through a keyword search).

4. Index terms allow for clarification of which entity you are talking about. This can be particularly helpful with identifying people and corporations. The scope and content may refer to Linsday Anderson, but the index entry will provide the dates and maybe an epithet to clarify that this is Lindsay Gordon Anderson, 1923-1994, film director. You could add this information to the scope and content, but it would tend to make it much more dense and arguably more difficult to read if you did this with all names. It would also imply that all names are of equal significance, and it would not be very helpful for machine processing unless you marked it up so that a machine could identify it as a personal name.

5. Index terms allow for connecting the same entity throughout the system. A very useful and powerful reason to have index terms. The main issue here is that contributors do not always enter the same thing, even with rules and sources to draw upon. Personal and corporate names are usually consistent, but inevitably the addition of the epithet, which is much more of an archival practice than a library practice, means that one person often has a number of different entries. If you took the epithet away, at least for the purposes of identifying the same entity, then things would work reasonably well. For subjects it’s more a case of just the amount of subjects that can be used to describe an archive. If you look for all the descriptions with the subject of ‘first world war’, then you won’t find all the descritions that are significantly about this subject because some of them are indexed with ‘world war one’, and other may use ‘war’ and ‘conflict’.

The way around this for the Hub is our ‘Subject Finder’. This is different from a straightforward subject search. It actually looks for similar terms and brings them together. So, a search for ‘first world war’ will bring back ‘world war one’. Similarly, a search for ‘railways’ will bring back the Library of Congress heading of ‘railroads’.

The Subject Finder helps, but does not comletely address this problem of the differing choice of terms. It cannot by-pass the fact that sometimes descriptions do not include any subject terms, so then they will not show up in a subject search. Recently I was looking for archives in the Hub on ‘exploration’, and was surprised to find that many of the Antarctic expeditions collections were not listed in the results. This was because some repositories did not use this subject term; a perfectly legitimate choice not to use it, but many other similar archives do use it.

I still feel that it is worth adding the significant entities as index terms, even with the problems of selecting what is ‘significant’ and with the inconsistencies that we have. Cataloguing as a whole is a subjective exercise, and it will never be perfect. For those who say that index terms are out-dated, I can only say that they are proving pretty useful for our current Linked Data project, and that is certainly pretty up to the minute in terms of Web technologies.

One final point in favour: the Archives Hub index terms exist within the descriptions as clickable links. This allows researchers to carry out ‘lateral’ searches, and it is a popular means to traverse descriptions, exploring from one subject to another, from one person to another.

Whether we should also consider enabling researchers to tag descriptions themselves is a whole other issue for another blog post…

This is not a complete case for and against by any means, but I think I’d better leave it there. I’d love to hear your views.