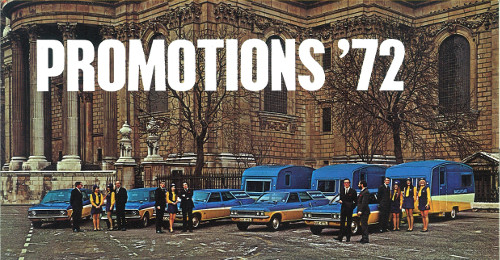

Archives Hub feature for November 2016

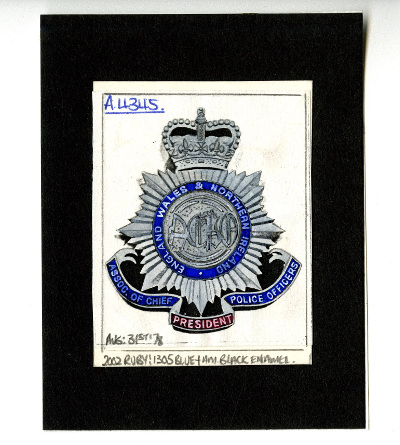

The Association of Chief Police Officers of England, Wales and Northern Ireland (ACPO) was formed in 1948, and disbanded in 2015. From 1964 it formed part of the tripartite system of governance over the police service. ACPO was the representative body for senior police officers until 1996, and contributed to the development of legislation, policing policy, training and procedure. The papers of this influential organisation were deposited at Hull History Centre in spring 2015, and the full catalogue will be released in January 2017. Amongst the collections’ diverse records are numerous items relating to the Association’s role in establishing the National Reporting Centre.

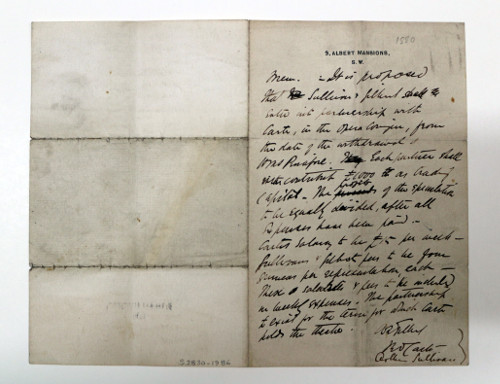

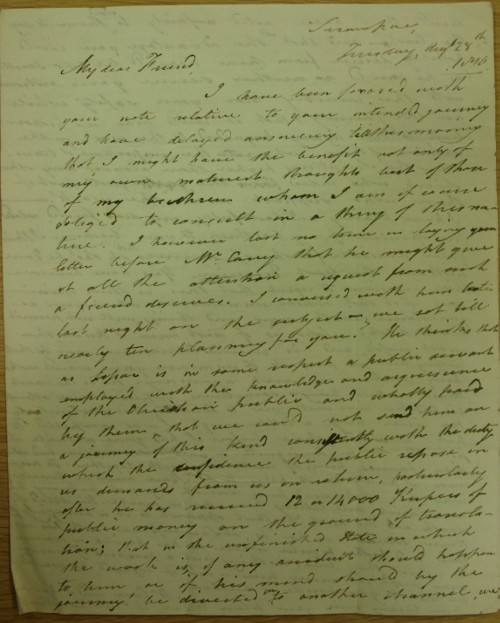

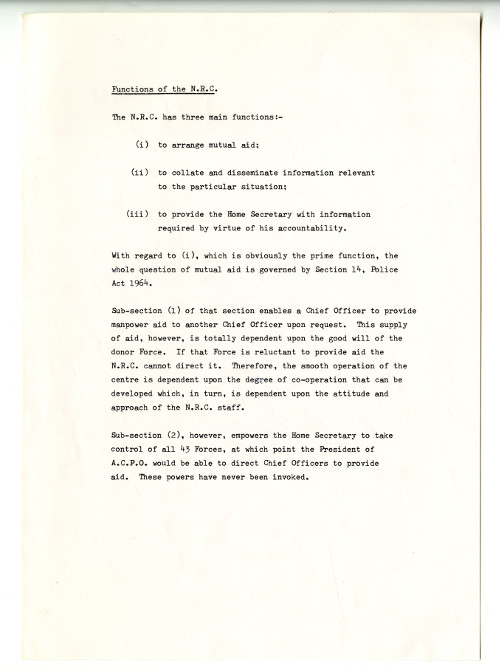

On the 4th of April 1972 a meeting was held at the Home Office to discuss the establishment of ‘a National Co-ordinating Centre for police resources’ [U DPO/8/1/1]. This was realised in the establishment of the National Reporting Centre (NRC). Section 14 of the Police Act of 1964 already allowed for the provision of constables from one force to another as additional resources. Based at New Scotland Yard, the NRC would serve as the coordinating body for enabling ‘nationally co-ordinated mutual aid’ [U DPO/8/1/1]. The centre would be led by ACPO, and any decision to activate it would be taken in consultation with the Home Office.

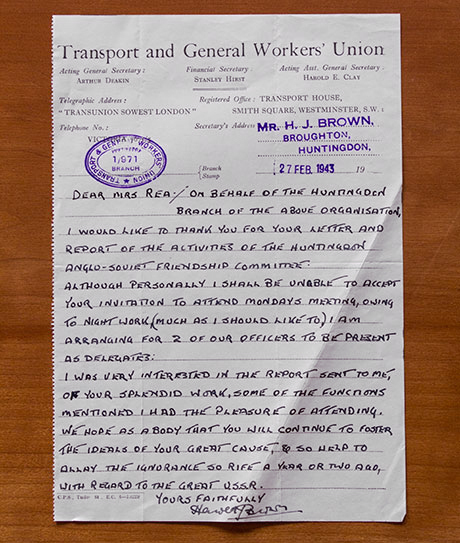

The first activation of the NRC came on the 10th of February 1974 in response to industrial action by the National Union of Miners (NUM). It remained open for less than a month. In 1980 it was active once again, co-ordinating the movement of prisoners during industrial action within the Prison Service [U DPO/8/1/1]. In March 1981 a one day exercise to test the Centre’s capabilities took place. An ACPO report found that it ‘predictably revealed the inability of the Centre to provide cohesive national coordination in a time of crisis’ [U DPO/8/1/42]. The report suggested that ‘Public disorder appears, unfortunately, to be a growth industry, and it is vital that the NRC should quickly become a practical reality’ [U DPO/8/1/42]. In the same year as the NRC exercise and subsequent report, Britain experienced social unrest in a series of riots in urban locations. Again the NRC was deployed, coordinating responses to chief officers’ requests for assistance in policing operations [U DPO/8/1/36a]. A further activation of the Centre in June 1982 coordinated forces for a visit to Britain by Pope John Paul II.

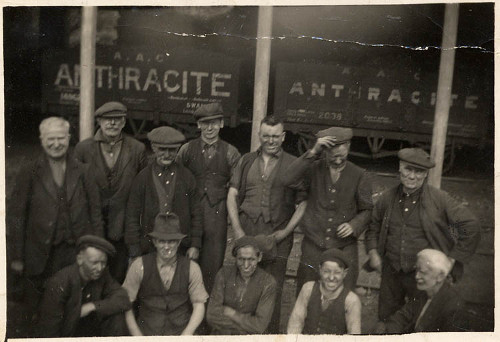

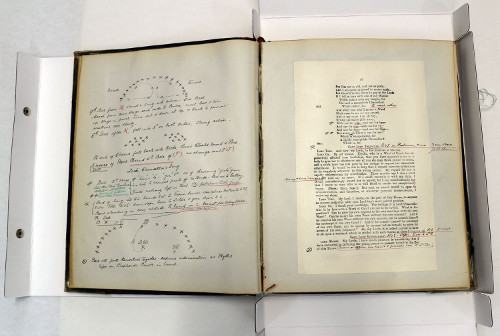

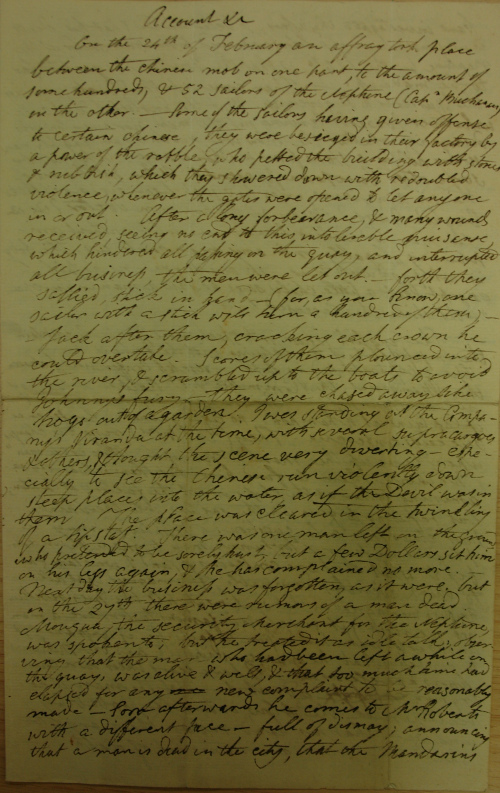

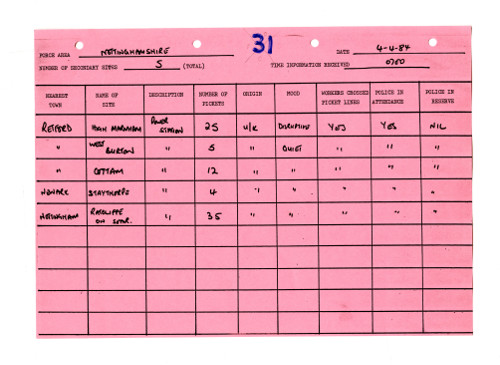

However, the NRC’s most well-known and controversial activation came in 1984, in response once again to industrial action by the NUM. Following the implementation of recommendations made in previous reports, increased training of mobile Police Support Units (PSUs), and new guidance on public order provided to senior officers, the NRC contributed to a highly mobile, national response to the strikes. The records in the ACPO collection include intelligence reports monitoring the picket lines and movement of potential flying pickets travelling between locations. These record not only the number and location of pickets, but the ‘mood’ as defined by the reporting officers, using a defined range of peaceful, hostile or violent [U DPO/8/1/42].

During this period of activation the centre was run by David Hall, then Chief Constable of Humberside as part of his duties as the serving President of ACPO. Shortly after the strikes ended The Times reported that the NRC had coordinated ‘more than one million movements of officers from almost all forces’ [4 March 1985 p.2]. The Centre’s aggregation of information and ability to coordinate cooperation between forces resulted in a highly responsive and mobile operation. Improved guidance issued by ACPO to Chief Officers in the form of a Tactical Options Manual combined with access to greater information via the NRC enabled individual chief officers to make decisions more tactically. The Centre continued operation until the strikes were called off on the 3rd of March 1985.

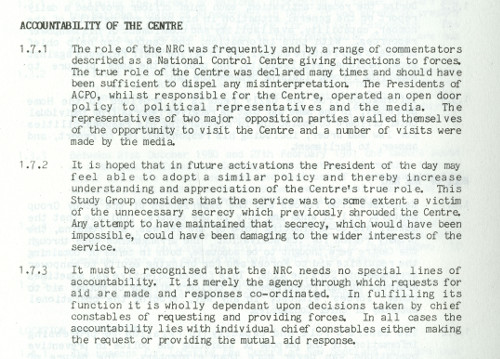

Although ACPO’s review of the operation concluded that the NRC’s role ‘was performed efficiently and demonstrated the essential requirement of the centre’ [U DPO/8/1/37], the Centre faced criticism within the press. This often related to the question of accountability. The Guardian reported that Hall, was ‘answerable to no-one… non-elected, non-accountable’ holding ‘more power than all the combined members of all the elected police authorities’ [7 September 1984 p.17]. Another article suggested there was ‘direct political control of policing operations’ via the NRC [The Guardian, 21 September 1984 p.2]. While calling for an inquiry into the policing of the strikes, former Home Secretary Merlyn Rees demanded control of the Centre be passed to the Home Office, [The Guardian, 16 May 1985 p.2].

In contrast, internal ACPO reports created in 1985 asserted that ‘the NRC needs no special lines of accountability. It is merely the agency through which requests for aid are made and responses coordinated… In all cases the accountability lies with individual chief constables’ [U DPO/8/1/36a]. In response to perceived ‘ignorance’ of both the public and the media to the Centre’s role, it was observed that ‘it is essential to remind people that the NRC is in reality a small group of officers working in a few offices and New Scotland Yard… and ultimately is accountable to the Home Office’ [U DPO/8/1/37].

The 1977 Ridley Report on nationalised industries directly referenced earlier NUM strike action, asserting a need for ‘a large, mobile squad of police… equipped and prepared to uphold the law against the likes of the Saltley Coke-works mob’ [http://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/110795]. The NRC arguably enabled the police to fulfil this recommendation, demonstrated by the controversial police response to the 1984-5 NUM strikes. While operation of the NRC was viewed internally as a success, the overall policing of the strikes remains controversial today. Although a small number of the NRC records within the ACPO papers are currently closed in accordance with the Data Protection Act (1998), the majority are open to public access. This will enable scrutiny of the data gathered and the flow of information, enabling researchers to make their own, informed decisions about the Centre’s role in this still contentious moment in recent British history.

Alexandra Healey

Project Archivist

Hull History Centre

Related:

Browse the Hull History Centre Collections on the Archives Hub.

Take a look at other collections on the subject of the Police.

Previous Hub feature – Liberty, Parity and Justice at the Hull History Centre.

All images copyright ACPO and reproduced with the kind permission of the copyright holder.