In January 2013 the Archives Hub became the UK ‘Country Manager’ for the Archives Portal Europe.

The Archives Portal Europe (APE) is a European aggregator for archives. The website provides more information about the APE vision:

Borders between European countries have changed often during the course of history. States have merged and separated and it is these changing patterns that form the basis for a common ground as well as for differences in their development. It is this tension between their shared history and diversity that makes their respective histories even more interesting. By collating archival material that has been created during these historical and political evolutions, the Archives Portal Europe aims to provide the opportunity to compare national and regional developments and to understand their uniqueness while simultaneously placing them within the larger European context.

The portal will help visitors not only to dig deeper into their own fields of interest, but also to discover new sources by giving an overview of the jigsaw puzzle of archival holdings across Europe in all their diversity.

For many countries, the Country Manager role is taken on by the national archives. However, for the UK the Archives Hub was in a good position to work with APE. The Archives Hub is an aggregation of archival descriptions held across the UK. We work with and store content in Encoded Archival Description (EAD), which provides us with a head start in terms of contributing content.

Jane Stevenson, the Archives Hub Manager, attended an APE workshop in Pisa in January 2013, to learn more about the tools that the project provides to help Country Managers and contributors to provide their data. Since then, Jane has also attended a conference in Dublin, Building Infrastructures for Archives in a Digital World, where she talked about A Licence to Thrill: the benefits of open data. APE has provided a great opportunity to work with European colleagues; it not just about creating a pan-European portal, it is also about sharing and learning together. At present, APE has a project called APEx, which is an initiative for “expanding, enriching, enhancing and sustaining” the portal.

How Content is Provided to APE

The way that APE normally works is through a Country Manager providing support to institutions wishing to contribute descriptions. However, for the UK, the Archives Hub takes on the role of providing the content directly, as it comes via the Hub and into APE. This is not to say that institutions cannot undertake to do this work themselves. The British Library, for example, will be working with their own data and submitting it to APE. But for many archives, the task of creating EAD and checking for validity would be beyond their resources. In addition, this model of working shows the benefits of using interoperable standards; the Archives Hub already processes and validates EAD, so we have a good understanding of what is required for the Archives Portal Europe.

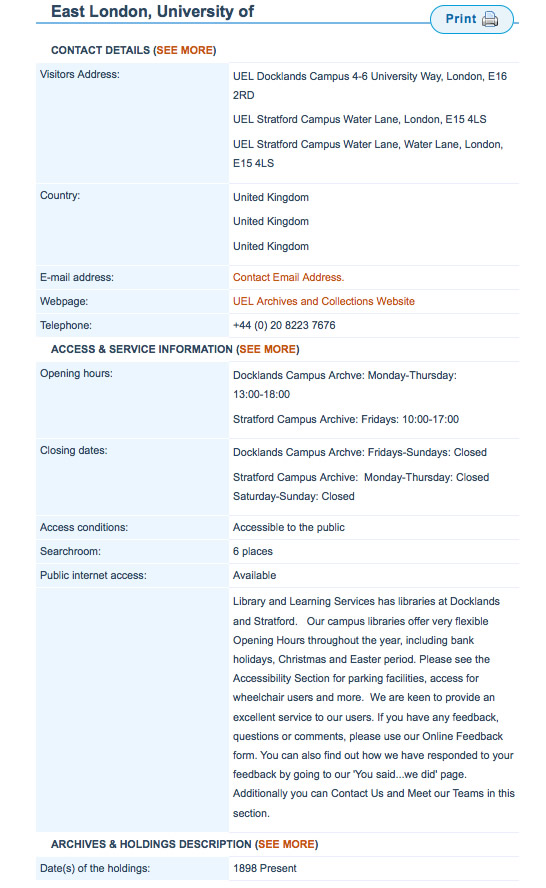

All that Archives Hub institutions need to do to become part of APE is to create their own directory entry. These entries are created using Encoded Archival Guide (EAG), but the archivist does not need to be familiar with EAG, as they are simply presented with a form to fill in. The directory entry can be quite brief, or very detailed, including information on opening hours, accessibility, reprographic services, search room places, internet access and the history of the archive.

Once the entry is created, we can upload the data. If the data is valid, this takes very little time to do, and immediately the archive is part of a national aggregation and a European aggregation.

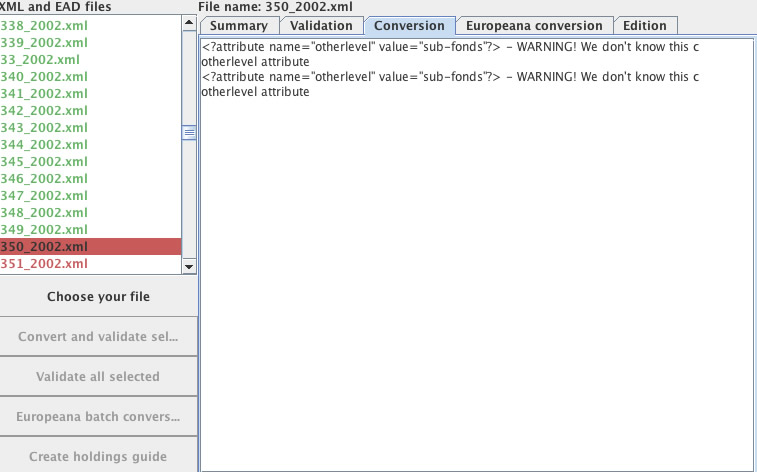

APE Data Preparation Tool

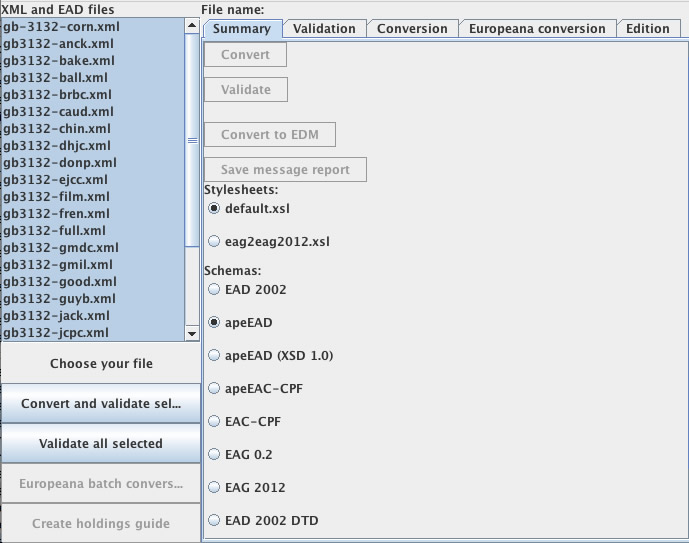

The Data Preparation Tool allows us to upload EAD content and validate it. You can see on the screen shot below a list of EAD files from the Mills Archive that have been uploaded to the Tool, and the Tool will allow us to ‘convert and validate’ them. There are various options for checking against different flavours of EAD and there is also the option to upload EAC-CPF (which is not something the Hub is working with as yet) and EAG.

If all goes according to plan, the validation results in a whole batch of valid files, and you are ready to upload the data. Sometimes there will be an invalid file and you need to take a look at the validation message and figure out what you need to do (the error message in this screenshot relates to ‘example 2’ below).

APE Dashboard

The Dashboard is an interface provided to an APE Country Manger to enable them to administer their landscape. The first job is to create the archival landscape. For the UK we decided to group the archives into type:

The landscape can be modified as we go, but it is good to keep the basic categories, so its worth thinking about this from the outset. We found that many other European countries divide their archives differently, reflecting their own landscape, particularly in terms of how local government is organised. We did have a discussion about the advantages of all using the same categories, but it seemed better for the end-user to be presented with categories suitable for the way UK archives are organised.

Within the Dashboard, the Country Manager creates logins for all of the archive repositories contributing to APE. The repositories can potentially use these logins to upload EAD to the dashboard, validate and correct if necessary and then publish. But at present, the Archives Hub is taking on this role for almost all repositories. One advantage of doing this is that we can identify issues that surface across the data, and work out how best to address these issues for all repositories, rather than each one having to take time to investigate their own data.

Working with the Data

When the Archives Hub started to work with APE, we began by undertaking a comparison of Hub EAD and APE EAD. Jane created a document setting out the similarities and differences between the two flavours of EAD. Whilst the Hub and APE both use EAD, this does not mean that the two will be totally compatible. EAD is quite permissive and so for services like aggregators choices have to be made about which fields to use and how to style the content using XSLT stylesheets. To try to cover all possible permutations of EAD use would be a huge task!

There have been two main scenarios when dealing with data issues for APE:

(1) the data is not valid EAD or it is in some way incorrect

(2) the data is valid EAD but the APE stylesheet cannot yet deal with it

We found that there were a combination of these types of scenarios. For the first, the onus is on the Archives Hub to deal with the data issues at source. This enables us to improve the data at the same time as ensuring that it can be ingested into APE. For the second, we explain the issue to the APE developer, so that the stylesheet can be modified.

Here are just a few examples of some of the issues we worked through.

Example 1: Digital Archival Objects

APE was omitting the <daodesc> content:

<dao href=”http://www.tate.org.uk/art/images/work/P/P78/P78315_8.jpg” show=”embed”><daodesc><p>’Gary Popstar’ by Julian Opie</p></daodesc></dao>

Content of <daodesc><p> should be transferred to <dao@xlink:title>. It would then be displayed as mouse-over text to the icons used in the APE for highlighting digital content. Would that solution be ok?

In this instance the problem was due to the Hub using the DTD and APE using the schema, and a small transformation done by APE when they ingested the data sufficed to provide a solution.

Example 2: EAD Level Attribute

Archivists are all familiar with the levels within archival descriptions. Unfortunately, ISAD(G), the standard for archival description, is not very helpful with enforcing controlled vocabulary here, simply suggesting terms like Fonds, Sub-fonds, Series, Sub-series. EAD has a more definite list of values:

- collection

- fonds

- class

- recordgrp

- series

- subfonds

- subgrp

- subseries

- file

- item

- otherlevel

Inevitably this means that the Archives Hub has ended up with variations in these values. In addition, some descriptions use an attribute value called ‘otherlevel’ for values that are not, in fact, other levels, but are recognised levels.

We had to deal with quite a few variations: Subfonds, SubFonds, sub-fonds, Sub-fonds, sub fonds, for example. I needed to discuss these values with the APE developer and we decided that the Hub data should be modified to only use the EAD specified values.

For example:

<c level=”otherlevel” otherlevel=”sub-fonds”>

needed to be changed to:

<c level=”subfonds”>

At the same time the APE stylesheet also needed to be modified to deal with all recognised level values. Where the level was not a recognised EAD value, e.g. ‘piece’, then ‘otherlevel’ is valid, and the APE stylesheet was modified to recognise this.

Example 3: Data within <title> tag

We discovered that for certain fields, such as biographical history, any content within a <title> tag was being omitted from the APE display. This simply required a minor adjustment to the stylesheet.

Where are we Now?

The APE developers are constantly working to improve the stylesheets to work with EAD from across Europe. Most of the issues that we have had have now been dealt with. We will continue to check the UK data as we upload it, and go through the process described above, correcting data issues at source and reporting validation problems to the APE team.

The UK Archival Landscape in Europe

By being part of the Archives Portal Europe, UK archives benefit from more exposure, and researchers benefit from being able to connect archives in new and different ways. UK archives are now being featured on the APE homepage.

APE and the APEx project provides a great community environment. It provides news from archives across Europe: http://www.apex-project.eu/index.php/news; it has a section for people to contribute articles: http://www.apex-project.eu/index.php/articles; it runs events and advertises events across Europe: http://www.apex-project.eu/index.php/events/cat.listevents/ Most importantly for the Archives Hub, it provides effective tools along with knowledgeable staff, so that there is a supportive environment to facilitate our role as Country Manager.

See: http://www.flickr.com/photos/apex_project/10723988866/in/set-72157637409343664/

(copyright: Bundersarchiv)