A comment on the blog post announcing the release of the Hub Linked Data maybe sums up what many archivists will think: “the main thing that struck me is that the data is very much for someone else (like a developer) rather than for an archivist. It is both ‘our data’ and not our data at the same time.”

Interfaces to the data

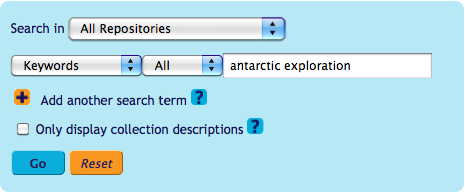

In many ways, Linked Data provides the same advantages as other machine based ways into the data. It gives you the ability to access data in a more unfiltered way. If you think about a standard Web interface search, what it does is to provide controlled ways into the data, and we present the data in a certain way. A user comes to a site, sees a keyword search box and enters a term, such as ‘antarctic exploration’. They have certain expectations of what they will get – some kind of list of results that are relevant to antarctica and famous explorers and expeditions – and yet they may not think much about the process – will all records that have any/either/both of these terms be returned, for example? Will the results be comprehensive? Might there be more effective ways to search for what they want? As those who run systems, we have to decide what a search is going to give the user. Will we look for these terms as adjacent terms and single terms? Will we return results from any field? How will we rank the results? We recently revised the relevance ranking on the Hub because although it was ‘pragmatically’ correct, it did not reflect what users expect to see. If a user enters ‘sir john franklin’ (with or without quotation marks) they would expect the Sir John Franklin Papers to come up first. This was not happening with the previous relevance ranking. The point here is that we (the service providers) decide – we have control over what the search returns and how it is displayed, and we do our best to provide something that will work for users.

Similarly, we decide how to display the results. We provide as a basis collection descriptions, maybe with lower-level entries, but the user cannot display information in different ways. The collection remains the indivisible unit.

With a Web interface we are providing (we hope) a user-friendly way to search for descriptions of archives – one that does not require prior knowledge. We know that users like a straightforward keyword search, as well as options for more advanced searching. We hide all of the mechanics of running the search and don’t really inform the user exactly what their search is doing in any kind of technical sense. When a user searches for a subject in the advanced subject search, they will expect to get all descriptions relating to that subject, but that is not necessarily what they will get. The reason is that the subject search looks for terms within the subject field. The creator of the description must put the subject in as an index term. In addition, the creator of the description may have entered a different term for the subject – say ‘drugs’ instead of ‘medicines’. The Archives Hub has a ‘subject finder’ that returns results for similar terms, so it would find both of these entries. However, maybe the case of the subject finder makes a good point about searching: it provides a really useful way to find results but it is quite hard to convey what it does quickly and obviously. It has never been widely used, even though evidence shows that users often want to search by subject, and by entering the subject as a keyword, they are more likely to get less relevant results.

These are all examples of how we, as service providers, look to find ways to make the data searchable in ways that we think users want and try to convey the search options effectively. But it does give a sense that they are coming into our world, searching ‘our data’, because we control how they can search and what they see.

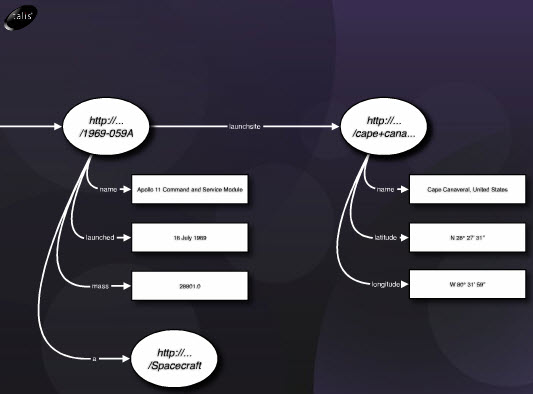

Linked Data is a different way of formatting data that is based upon a model of the entities in the data and relationships between them. To read more about the basics of Linked Data take a look at some of the earlier posts on the Locah blog (http://blogs.ukoln.ac.uk/locah/2010/08/).

Providing machine interfaces gives a number of benefits. However, I want to refer to two types of ‘user’ here. The ‘intermediate user’ and the ‘end user’. The intermediate user is the one that gets the data and creates the new ways of searching and accessing the data. Typically, this may be a developer working with the archivist. But as tools are developed to faciliate this kind of work, it should become easier to work with the data in this way. The end user is the person who actually wants to use the data.

1) Data is made available to be selected and used in different ways

We want to provide the ability for the data to be queried in different ways and for users to get results that are not necessarily based upon the collection description. For example, the intermediate user could select only data that relates to a particular theme, because they are representing end users who are interested in combining that data with other sources on the same theme. The combined data can be displayed to end users in ways that work for a particular community or particular scenario.

The display within a service like the Hub is for the most part unchanging, providing consistency, and it generally does the job. We, of course, make changes and enhancements to improve the service based on user needs from time to time, but we’re still essentially catering for one generic user as best we can, However, we want to provide the potential to allow users to display data in their own way for their own purposes. Linked Data encourages this. There are other ways to make this possible of course, and we have an SRU interface that is being used by the Genesis portal for Women’s Studies. The important point is that we provide the potential for these kinds of innovations.

2) External links begin the process of interconnecting data

Machine interfaces provide flexible ways into the data, but I think that one of the main selling points of Linked Data is, well, linking data. To do this with the Hub data, we have put some links in to external datasets. I will be blogging about the process of linking to VIAF names (Virtual International Name Authority File), but suffice to say that if we can make the statement within our data that ‘Sir Ernest Shackleton’ on the Hub is the same as ‘Sir Ernest Shackleton’ on VIAF then we can benefit from anything that VIAF links to DBPedia for example (Wikipedia output as Linked Data). A user (or intermediate user) can potentially bring together information on Sir Ernest Shackleton from a wide range of sources. This provides a means to make data interconnected and bring people through to archives via a myriad of starting points.

3) Shared vocabularies provide common semantics

If we identify the title of a collection by using Dublin Core, then it shows that we mean the same thing by ‘title’ as others who use the Dublin Core title element. If we identify ‘English’ by using a commonly recognised URI (identifier) for English, from a common vocabulary (lexvo), then it shows that we mean the same thing as all the other datasets that use this vocabulary. The use of common vocabularies provides impetus towards more interoperability – again, connecting data more effectively. This brings the data out of the archival domain (where we share standards and terminology amongst our own community) and into a more global space. It provides the potential for intermediate users to understand more about what our data is saying in order to provide services for end users. For example, they can create a cross-search of other data that includes titles, dates, extent, creator, etc. and have reasonable confidence that the cross-search will work because they are identifying the same type of content.

For the Hub there are certain entities where we have had to create our own vocabulary, because those in existence do not define what we need, but then there is the potential for other datasets to use the same terms that we use.

4) URIs are provided for all entities

For Linked Data one of the key rules is that entities are identified with HTTP URIs. This means that names, places, subjects, repositories, etc. within the Hub data are now brought to the fore through having their own identifier – all the individuals, for example, within the index terms, have their own URI. This allows the potential to link from the person identified on the Hub to the same person identified in other datasets.

Who is the user?

So far so good. But I think that whilst in theory Linked Data does bring significant benefits, maybe there is a need to explain the limitations of where we are currently at.

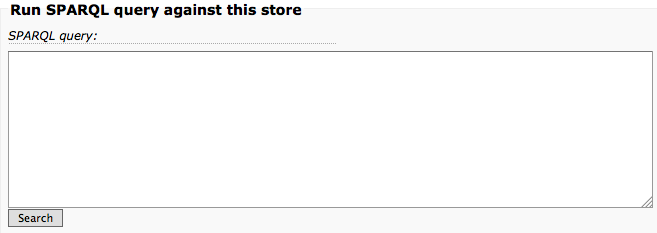

Our Linked Data cannot currently be accessed via a human user friendly Web-based search interface; it can however be accessed via a Sparql endpoint. Sparql is the language for querying RDF, the format used for Linked Data. It shares many similarities to SQL, a language typically used for querying conventional relational databases that are the basis of many online services. (Our Sparql endpoint is at http://data.archiveshub.ac.uk/sparql ). What this means is that if you can write Sparql queries then you’re up and running. Most end users can’t, so they will not be able to pull out the data in this way. Even once you’ve got the data, then what? Most people wouldn’t know what to do with RDF output. In the main, therefore, fully utilising the data requires technical ability – it requires intermediate users to work with the data and create tools and services for end users.

For the Hub

we have provided Linked Data views, but it is important not to misunderstand the role of these views – they are not any kind of definite presentation, they are simply a means to show what the data consists of, and the user can then access that data as RDF/XML, JSON or Turtle (i.e. in a number of formats). It’s a human friendly view on the Linked Data if you access a Hub entity web address via a web browser. If however, you are a machine wanting machine readable RDF visiting the very same URI, you would get the RDF view straight off. This is not to say that it wouldn’t be possible to provide all sorts of search interfaces onto the data – but this is not really the point of it for us at the moment – the point is to allow other people to have the potential to do what they want to do.

The realisation of the user benefit has always been the biggest question mark for me over Linked Data – not so much the potential benefits, as the way people perceive the benefits and the confidence that they can be realised. We cannot all go off and create cool visualisations (e.g. http://www.simile-widgets.org/timeline/). However, it is important to put this into perspective. The Hub data at Mimas sits in directories as EAD XML. Most users wouldn’t find that very useful. We provide an interface that enables users with no technical knowledge to access the data, but we control this and it only provides access to our dataset and to a collection-based view. In order to step beyond this and allow users to access the data in different ways, we necessarily need to output it in a way that provides this potential, but there is likely to be a lag before tools and services come along that take advantage of this. In other words, what we are essentially doing is unlocking more potential, but we are not necessarily working with that potential ourselves – we are simply putting it out there for others.

Having said that, I do think that it is really important for us to now look to demonstrate the benefits of Linked Data for our service more clearly by providing some ways into the Linked Data that take advantage of the flexible nature of the data and the external links – something that ‘ordinary’ users can benefit from. We are looking to work on some visualisations that do demonstrate some of the potential. There does seem to be an increasing consensus within cultural heritage that primary resources are too severed from the process of research – we have a universe of unrelated bits that hint at what is possible but do not allow it to be realised. Linked Data is attempting to resolve this, so it’s worth putting some time and effort into exploring what it can do.

We want our data to be available so that anyone can use it as they want. It may be true that the best thing done with the data will be thought of by someone else. (see Paul Walk’s blog post for a view on this).

However, this is problematic when trying to measure impact, and if we want to understand the benefits of Linked Data we could do with a way to measure them. Certainly, we can continue to work to realise benefits by actively working with the Linked Data community and encouraging a more constructive and effective relationship between developers and managers. It seems to me that things like Linked Data require us to encourage developers to innovate and experiment with the data, enabling users to realise its benefits by taking full advantage of the global interconnectivity that is the vision of the Linked Data Web. This is the aim of UKOLN’s Dev CSI project – something I think we should be encouraging within our domain.

So, coming back to the starting point of this blog: The data maybe starts off as ‘our data’ but really we do indeed want it to be everyone’s data. A pick ‘n pix environment to suit every information need.