Archives Hub feature for September 2019

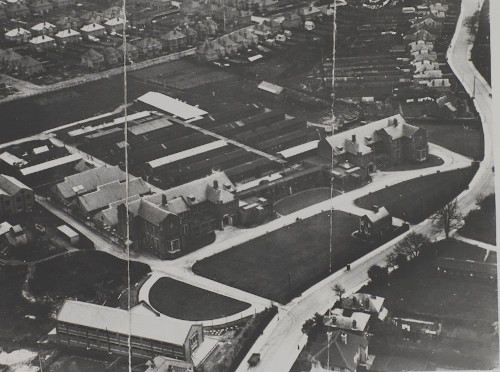

Part of an ambitious expansion plan by the University College, Southampton, the first developments at the Highfield Campus were completed in 1914, shortly before the start of the First World War. The College decided to remain in its City Centre base and the Highfield buildings were used as a War Hospital. When the College moved to Highfield in the autumn of 1919, many of the buildings bore “honourable scars” from their service as a hospital and the accommodation was supplemented by the wooden huts added to provide additional wards.

Traces of the hospital origins of some of the additional accommodation – such as the inscription ‘dysentery’ on the door of the staff refectory – were to remain for some time. And for the Principal, Kenneth Vickers, who was appointed in 1922, a priority was not only creating halls of resident for students but improving the buildings on campus. Vickers noted: “On my first day in College I was waylaid by the Professor of Physics who was alarmed at the dangerous condition of his first floor lecture room, which was showing signs of subsiding […]” Vickers, alongside the President, Claude Montefiore, were two of the notable individuals responsible for the development of the College during the 1920s.

Whilst the 1930s were a bad time for the College, amongst developments was the creation of a new library, remedying the most serious lack in facilities since the move to the Highfield campus. Made possible by a substantial donation from Margaret and Mary Turner Sims, the Turner Sims Library was opened in October 1935 by the Duke of York (later King George VI). Described as having a “commodious reading room”, the Library also boasted a stack room for 12,000 volumes and six seminar rooms and was to prove an attractive space for students.

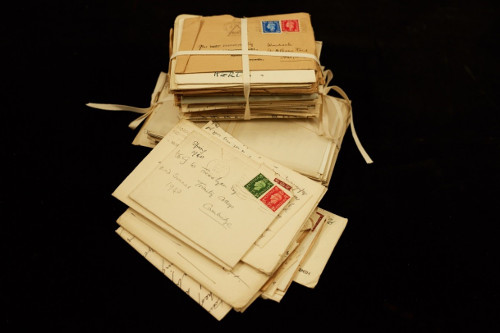

The Second World War was a period of both anxiety and opportunity for University College, Southampton. The decision not to evacuate the Highfield site allowed the College to play a full part in wartime training and education and in research related to the war effort, but meant that students and staff were potentially at risk from enemy action.

Student Nora Harvey noted of the air raid precautions: “We have elaborate sheets of cardboard up at Highfield windows which are fixed up with strips of wood slipping into slots at the side… In air raids we are going to congregate in one of the downstairs corridors. It is awfully safe apparently as there are two cement and steel floors above us there and rooms all round and no windows at all.”

Wartime brought other restrictions on student life with all male students on full-time courses required to join the Senior Training Corps or University Air Squadron, student societies forced to close due to pressure of time and travel difficulties affecting sporting fixtures. Entertainment continued as far as possible, although dances were forced to end at 8.30pm, causing “considerable feeling” amongst the student body.

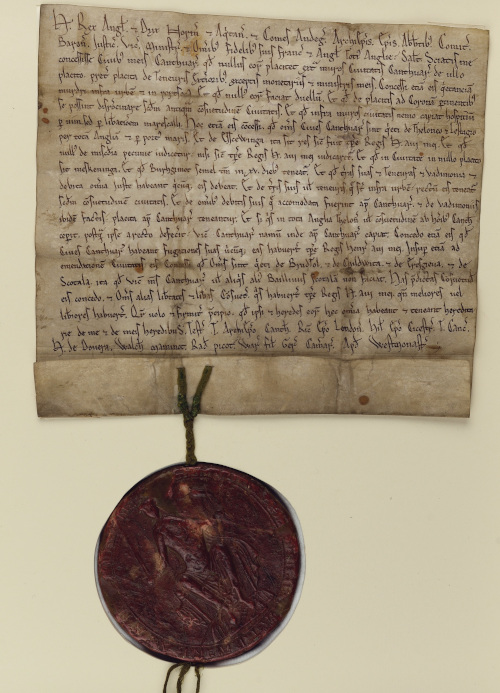

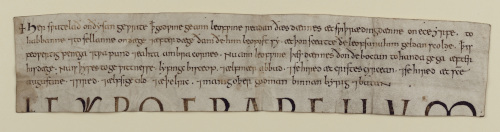

In 1952 Southampton became the first university to be created in the reign of Queen Elizabeth II, receiving its royal charter on 29 April of that year. The University of Southampton Act received its Royal Assent on 6 May 1953 and on 3 July the ceremonious installation of new Chancellor, the Duke of Wellington, took place at the Guildhall in Southampton. As part of these celebrations, a message was carried in relay by members of the Southampton Athletics Union from the Chancellor of the University of London to be presented to the Duke.

The “swinging sixties” were a decade of significant growth and expansion for the university. Key to the development of the Highfield site was architect Sir Basil Spence who had been charged with creating a “master plan” for the Highfield Campus and all the major buildings of this period were designed by him.

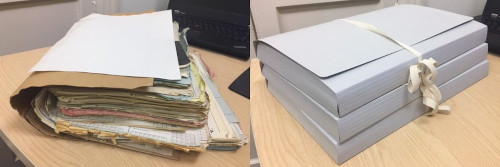

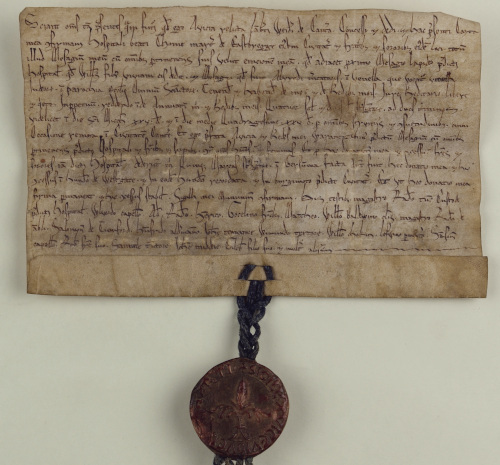

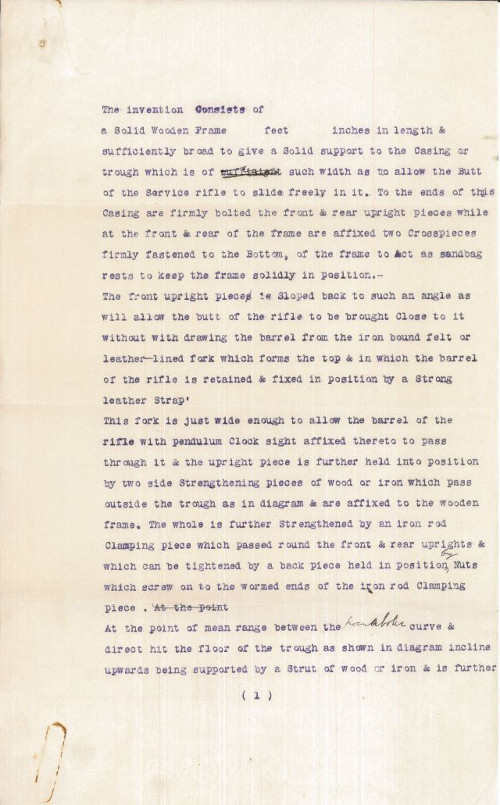

The Highfield campus has been the focus of much development in the subsequent decades as the University has expanded to meet growing demands and changes within the higher education sector. Significant for the Special Collections was the development of the Archives Department from 1982 to house the newly acquired papers of the first Duke of Wellington and the creation of new archival facilities as part of a 2002-4 expansion of the Hartley Library.

From the formality of the earlier decades of the twentieth century – even in the 1950s “it was still an era when all students were required to wear a black academic gown at dinner in the evening” – student life has developed to reflect the concerns and interests of its times. The 1960s saw the beginnings of student protest. These varied from a boycott of the refectory about the quality of the food to support for national and international causes. In later decades, student protests have encompassed a wide range of issues, including opposition to the introduction of loans.

Sporting endeavour has been a constant throughout the history of University life: from a relatively modest number of sporting societies in the early student days to everything from Aerial Sports to Zumba covered in 2019. Another constant has been the annual RAG, traditionally a highlight of the Winter term. In earlier decades this featured a procession of decorated floats on lorries through the city centre. During the 1950s “the Engineers were always very prominent during Rag … often accompanied by their human skeleton mascot ‘Kelly’.”

For more on Highfield 100, see the Special Collections monthly posts charting the progress of the University decade by decade since 1919: https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.wordpress.com/?s=highfield+100

Karen Robson

Archives and Manuscripts

Hartley Library

University of Southampton

Related

Papers of K.H.Vickers, 1920s-1958

Papers of C.J. Goldsmid-Montefiore, 1885-1935

Browse all University of Southampton Special Collections descriptions on the Archives Hub.

Previous features on University of Southampton Special Collections:

The Basque Child Refugee Archive

60 years of faith and conflict

All images copyright University of Southampton Special Collections and reproduced with the kind permission of the copyright holders.

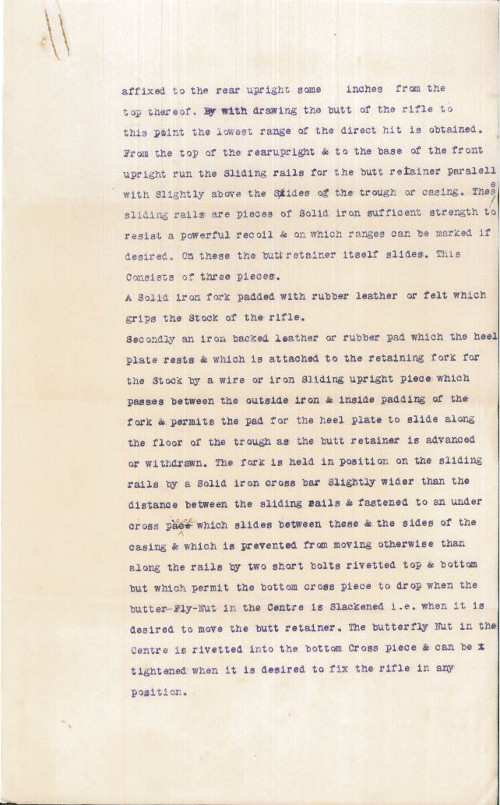

![Letter from W.S. Kneeshaw to ‘Trevor’ [Mr Trevor of Carter Vincent, Solicitors, Bangor] regarding an invention he intends to patent](https://blog.archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/04/cvabangor_letter.jpg)

![Career guide for married women pursuing paediatrics produced by the BPA due to the increasing number of women graduating in medicine, of which many left the profession due to family commitments. The document proposes that establishing suitable posts and offering retraining schemes and financial inducements could support female paediatricians. 1972 [archive reference: RCPCH/007/141]](https://blog.archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/03/rcpch_guide.jpg)

![Minutes of a meeting of the Executive Committee discussing whether to invite female members of the Canadian Paediatrics Society to a joint meeting in London, 1938 [archive reference: RCPCH/004/002/006]](https://blog.archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/03/rcpch_min1938.jpg)

![Minutes of a meeting of the Executive Committee showing the vote to admit female members into the BPA, 1944 [archive reference: RCPCH/004/003/011]](https://blog.archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/03/rcpch_min1944.jpg)

![Painted design of the RCPCH Coat of Arms featuring June Lloyd, 1997 [archive reference: RCPCH/009/001/014]](https://blog.archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/03/rcpch_coatofarms.jpg)

![Photograph of an early ‘floating institute’ operated by the Missions to Seamen, late 19th century [U DMS].](https://blog.archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/01/seam_institute.jpg)

![Logo of the Flying Angel [U DMS].](https://blog.archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/01/seam_angel.jpg)

![Logo of the Stella Maris [U DAPS/12/4].](https://blog.archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/01/seam_stella.jpg)

![Photograph of the interior of the original Apostleship of the Sea house in Glasgow, c.1920s [U DAPS/7/2].](https://blog.archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/01/seam_house.jpg)

![Photograph of a visit paid to Bishop Rock lighthouse by Missions to Seamen representatives for the Scilly Isles [U DMS].](https://blog.archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/01/seam_visit.jpg)