A HEFCE study from 2010 states that “96% of students use the internet as a source of information” (1). This makes me wonder about the 4% that don’t; it’s not an insignificant number. The same study found that “69% of students use the internet daily as part of their studies”, so 31% don’t use it on a daily basis (which I take to mean ‘very frequently’).

There have been many reports on the subject of technology and its impact on learning, teaching and education. This HEFCE/NUS study is useful because it concentrates on surveying students rather than teachers or information professionals. One of the key findings is that it is important to think about the “effective use of technology” and “not just technology for technology’s sake”. Many students still find conventional methods of teaching superior (a finding that has come up in other studies), and students prefer a choice in how they learn. However, the potential for use of ICT is clear, and the need to engage with it is clear, so it is worrying that students believe that a significant number of staff “lack even the most rudimentary IT skills”. It is hardy surprising that the experiences of students vary considerably when they are partly dependent upon the skills and understanding of their teachers, and whether teachers use technology appropriately and effectively.

At the recent ELAG conference I gave a joint presentation with Lukas Koster, a colleague from the University of Amsterdam, in which we talked about (and acted out via two short sketches) the gap between researchers’ needs and what information professionals provide. Thinking simply about something as seemingly obvious as the understanding and use of

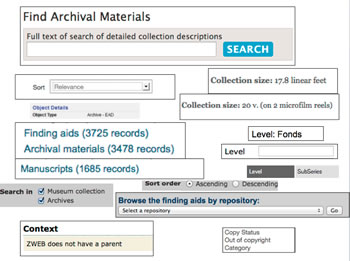

the term ‘archives’ is a good case in point. Should we ensure that students understand the different definitions of archives? The distinction between archives that are collections with a common provenance and archives that are artificial collections? The different characters of archives that are datasets, generally used by social scientists? The “abuse” of the term archives for pretty much anything that is stored in any kind of longer-term way? Should users understand archival arrangement and how to drill down into collections? Should they understand ‘fonds’, ‘manuscripts’, ‘levels’, ‘parent collection’? Or is it that we should think more about how to translate these things into everyday language and simple design, and how to work things like archival hierarchy into easy-to-use interfaces? I think we should take the opportunities that technology provides to find ways to present information in such a way that we facilitate the user experience. But if students are reporting a lack of basic ICT skills amongst teachers, you have to wonder whether this is a problem within the archive and library sector as well. Do information professionals have appropriate ICT skills fit for ensuring that we can tailor our services to meet the needs of the technically savvy user?

Should we be teaching information literacy to students? One of the problems with this idea is that they tend to think they are already pretty literate in terms of use of the internet. In the HEFCE report, a survey of 213 FE students found that 88% felt they were effective online researchers and the majority said they were self-taught. They would not be likely to attend training on how to use the internet. And there is a question over whether they need to be taught how to use it in the ‘right’ way, or whether information professionals should, in fact, work with the reality of how it is being used (even if it is deemed to be ‘wrong’ in some way). Students are clear that they do want training “around how to effectively research and reference reliable online resources”, and maybe this is what we should be concentrating on (although it might be worth considering what ‘effective use of the internet’ and ‘effective research using the internet’ actually mean). Maybe this distinction highlights the problem with how to measure effective use of the internet, and how to define online or discovery skills.

A British Library survey from 2010 found that “only a small proportion [of students] …are using technology such as virtual-research environments, social bookmarking, data and text mining, wikis, blogs and RSS-feed alerts in their work.” This is despite the fact that many respondents in the survey said they found such tools valuable. This study also showed that students turn to their peers or supervisors rather than library staff for help.

Part of the problem may be that the vast majority of users use the internet for leisure purposes as well as work or study, so the boundaries can become blurred, and they may feel that they are adept users without distinguishing between different types of use. They feel that they are ‘fine with the technology’, although I wonder if that could be because they spend hours playing World of Warcraft, or use Facebook or Twitter every day, or regularly download music and watch YouTube. Does that mean they will use technology in an effective way as part of their studies? The trouble is that if someone believes that they are adept at searching, they may not go that extra mile to reflect on what they are doing and how effective it really is. Do we need to adjust our ways of thinking to make our resources more user-friendly to people coming from this kind of ‘I know what I’m doing’ mindset, or do we have to disabuse them of this idea and re-train them (or exhort them to read help pages for example…which seems like a fruitless mission)? Certainly students have shown some concern over “surface learning” (skim reading, learning only the minimum, and not getting a broader understanding of issues), so there is some recognition of an issue here, and the tendency to take a superficial approach might be reinforced if we shy away from providing more sophisticated tools and interfaces.

The British Library report on the Information Behaviour of the Researcher of the Future reinforces the idea that there is a gulf between students’ assumptions regarding their ICT skills versus the reality, which reveals a real lack of understanding. It also found a significant lack of training in discovery and use of tools for postgraduate students. Studies like this can help us think about how to design our websites, and provide tools and services to help researchers using archives. We have the challenges of how to make archives more accessible and easy to discover as well as thinking about how to help students use and interpret them effectively: “The college students of the open source, open content era will distinguish themselves from their peers and competitors, not by the information they know, but by how well they convert that knowledge to wisdom, slowly and deeply internalized.” (Sheila Stearns, “Literacy in the University of 2025: Still A Great Thing‟, from The Future of Higher Education , ed. by Gary Olson & John W Presley, (Boulder: Paradigm Publishers, 2009) pp. 98-99).

What are the Solutions?

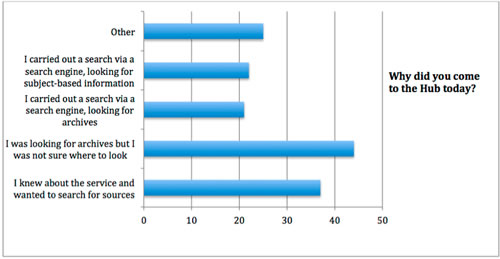

We should make user testing more integral to the development of our interfaces. It requires resource, but for the Archives Hub we found that even carrying out 10 one-hour interviews with students and academics helped us to understand where we were making assumptions and how we could make small modifications that would improve our site. And our annual online survey continues to provide really useful feedback which we use to adjust our interface design, navigation and terminology. We can understand more about our users, and sometimes our assumptions about them are challenged.

User groups for commercial software providers can petition to ensure that out-of-the-box solutions also meet users’ needs and take account of the latest research and understanding of users’ experiences, expectations and preferences in terms of what we provide for them. This may be a harder call, because vendors are not necessarily flexible and agile; they may not be willing to make radical changes unless they see a strong business case (i.e. income may be the strongest factor).

We can build a picture of our users via our statistics. We can look at how users came into the site, the landing pages, where they went from there, which pages are most/least popular, how long they spent on individual pages, etc. This can offer real insights into user behaviour. I think a few training sessions on using Google Analytics on archive sites could come in handy!

We can carry out testing to find out how well sites rank on search engines, and assess the sort of experience users get when they come into a specialist site from a general search engine. What is the text a Google search shows when it finds one of your collections? What do people get to when they click on that link? Is it clear where they are and what they can do when they get to your site?

* * *

This is the only generation where the teachers and information professionals have grown up in a pre-digital world, and the students (unless they are mature students) are digital natives. Of course, we can’t just sit back and wait a generation for the teachers and information professionals to become more digitally minded! But it is interesting to wonder whether in 25 years time there will be much more consensus in approaches to and uses of ICT, or whether the same issues will be around.

Nigel Shadbolt has described the Web as “one of the most disruptive innovations we have ever witnessed” and at present we really seem to be struggling to find out how best to use it (and not use it), how and when to train people to use it and how and when to integrate it into teaching, learning and research in an effective way.

It seems to me that there are so many narratives and assessments at present – studies and reports that seem to run the gamut of positive to negative. Is technology isolating or socialising? Are social networks making learning more superficial or enabling richer discussion and analysis? Is open access democratising or income-reducing? Is the high cost of technology encouraging elitism in education? Does the fact that information is so easily accessible mean that researchers are less bothered about working to find new sources of information? With all these types of debates there is probably no clear answer, but let us hope we are moving forward in understanding and in our appreciation of what the Web can do to both enhance and transform learning, teaching and research.