Last week I attended a very full and lively Europeana Tech conference. Here are some of the main initiatives and ideas I have taken away with me:

Think in terms of improvement, not perfection

Do the best you can with what you have; incorrect data may not be as bad as we think and maybe users expectations are changing, and they are increasingly willing to work with incomplete or imperfect data. Some of the speakers talked about successful crowd-sourcing – people are often happy to correct your metadata for you and a well thought-out crowd-sourcing project can give great results.

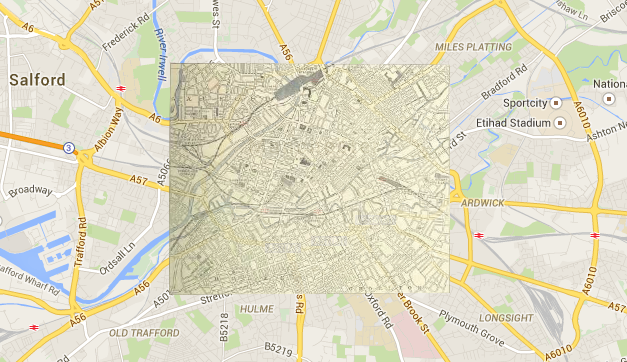

The British Library currently have an initiative to encourage tagging of their images on Flickr Commons and they also have a crowd-sourcing geo-referencer project.

The Cooper Hewitt Museum site takes a different and more informal approach to what we might usually expect from a cultural heritage site. The homepage goes for an honest approach:

“This is a kind of living document, meaning that development is ongoing — object research is being added, bugs are being fixed, and erroneous terms are being revised. In spite of the eccentricities of raw data, you can begin exploring the collection and discovering unexpected connections among objects and designers.”

The ‘here is some stuff’ and ‘show me more stuff’ type of approach was noticeable throughout the conference, with different speakers talking about their own websites. Seb Chan from the Cooper Hewitt Museum talked about the importance of putting information out there, even if you have very little, it is better than nothing (e.g. https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18446665).

The speaker from Google, Chris Welty, is best known for his work on ontologies in the Semantic Web and IBM’s Watson. He spoke about cognitive computing, and his message was ‘maybe it’s OK to be wrong’. Something may well still useful, even if it is not perfectly precise. We are increasingly understanding that the Web is in a state of continuous improvement, and so we should focus on improvement, not perfection. What we want is for mistakes to decrease, and for new functionality not to break old functionality. Chris talked about the importance of having a metric – something that is believable – that you can use to measure improvement. He also spoke about what is ‘true’ and the need for a ‘ground truth’ in an environment where problems often don’t have a right or wrong answer. What is the truth about an image? If you show an image to a human and ask them to talk about it they could talk for a long time. What are the right things to say about it? What should a machine see? To know this, or to know it better, Chris said, Google needs data – more and more and more data. He made it clear that the data is key and it will help us on the road to continuous improvement. He used the example of searching for pictures of flowers using Google to find ‘paintings with flowers’. If you did this search 5 years ago you probably wouldn’t get just paintings with flowers. The search has improved, and it will continue to improve. A search for ‘paintings with tulips’ now is likely to show you just tulips. However, he gave the example of ‘paintings with flowers by french artists’ – a search where you start to see errors as the results are not all by french artists. A current problem Google are dealing with is mixed language queries, such as ‘paintings des fleurs’, which opens a whole can of worms. But Chris’ message was that metadata matters: it is the metadata that makes this kind of searching possible.

The Success of Failure

Related to the point about improvement, the message is that being ‘wrong’ or ‘failing’ should be seen in a much more positive light. Chris Welty told us that two thirds of his work doesn’t make it into a live environment, and he has no problem with that. Of course, it’s hard not to think that Google can afford to fail rather more than many of us! But I did have an interesting conversation with colleagues, via Twitter, around the importance of senior management and funders understanding that we can learn a great deal from what is perceived as failure, and we shouldn’t feel compelled to hide it away.

Think in terms of Entities

We had a small group conversation where this came up, and a colleague said to me ‘but surely that’s obvious’. But as archivists we have always been very centered on documents rather than things – on the archive collection, and the archive collection description. The trend that I was seeing reflected at Europeana Tech continued to be towards connections, narratives, pathways, utilising new tools for working with data, for improving data quality and linking data, for adding geo-coordinates and describing new entities, for making images more interoperable and contextualising information. The principle underlying this was that we should start from the real world – the real world entities – and go from there. Various data models were explored, such as the Europeana Data Model and CIDOC CRM, and speakers explained how entities can connect, and enable a richer landscape. Data models are a tricky one because they can help to focus on key entities and relationships, but they can be very complex and rather off-putting. The EDM seems to split the crowd somewhat, and there was some criticism that it is not event-based like CIDOC CRM, but the CRM is often criticised for being very complex and difficult to understand. Anyway, setting that aside, the overall the message was that relationships are key, however we decide to model them.

Cataloguing will never capture everyone’s research interests

An obvious point, but I thought it was quite well conveyed in the conference. Do we catalogue with the assumption that people know what they need? What about researchers interested in how ‘sad’ is expressed throughout history, or fashions for facial hair, or a million other topics that simply don’t fit in with the sorts of keywords and subject terms we normally use. We’ll never be able to meet these needs, but putting out as much data as we can, and making it open, allows others to explore, tag and annotate and create infinite groups of resources. It can be amazing and moving, what people create: Every3Minutes.

There’s so much out there to explore….

There are so many great looking tools and initiatives worth looking at, so many places to go and experiment with open data, so many APIs enabling so much potential. I ended up with a very long list of interesting looking sites to check out. But I couldn’t help feeling that so few of us have the time or resource to actually take advantage of this busy world of technology. We heard about Europeana Labs, which has around 100 ‘hardcore’ users and 2,200 registered keys (required for API use). It is described as “a playground for remixing and using your cultural and scientific heritage. A place for inspiration, innovation and sharing.” I wondered if we would ever have the time to go and have a play. But then maybe we should shift focus away from not being able to do these things ourselves, and simply allow others to use the data, and to adopt the tools and techniques that are available – people can create all sorts of things. One example amongst many we heard about at the conference is a cultural collage: zenlan.com/collage. It comes back to what is now quite an old adage, ‘the best innovation may not be done by you’. APIs enable others to innovate, and what interests people can be a real surprise. Bill Thompson from the BBC referred to a huge interest in old listings from Radio Times, which are now available online.

The International Image Interoperability Framework

I list the IIIF this because it jumped out at me as a framework that seems to be very popular – several speakers referred to it, and it very positive terms. I hadn’t heard of it before, but it seemed to be seen as a practical means to ensure that images are interoperable, and can be moved around different systems.

Think Little

One of my favourite thoughts from the conference, from the ever-inspirational Tim Sherratt, was that big ideas should enable little ideas. The little ideas are often what really makes the world go round. You don’t have to always think big. In fact, many sites have suffered from the tendency to try to do everything. Just because you can add tons of features to your applications, it doesn’t mean you should

The Importance of Orientation

How would you present your collections if you didn’t have a search box? This is the question I asked myself after listening to George Oates, from Good Form and Spectacle. She is a User Interface expert, and has worked on Flickr and for the Internet Archive amongst other things. I thought her argument about the need to help orientate users was interesting, as so often we are told that the ‘Google search box’ is the key thing, and what users expect. She talked about some of her experiments with front end interfaces that allow users to look at things differently, such as the V&A Spelunker. She spoke in terms of landmarks and paths that users could follow. I wonder if this is easier said than done with archives without over-curating what you have or excluding material that is less well catalogued, or does not have a nice image to work with. But I certainly think it is an idea worth exploring.