£14.5m awarded to transform online exploration of UK’s culture and heritage collections through harnessing innovative AI

The Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) has awarded £14.5m to the research and development of emerging technologies, including machine learning and citizen-led archiving, in order to connect the UK’s cultural artefacts and historical archives in new and transformative ways.

The Archives Hub is pleased to announce that we will be a project partner in one of five major projects being launched today. The projects form the largest investment of Towards a National Collection, a five-year research programme. Today’s launch reveals the first insights into how thousands of disparate collections could be explored by public audiences and academic researchers in the future.

The five ‘Discovery Projects’ will harness the potential of new technology to dissolve barriers between collections – opening up public access and facilitating research across a range of sources and stories held in different physical locations. One of the central aims is to empower and diversify audiences by involving them in the research and creating new ways for them to access and interact with collections. In addition to innovative online access, the projects will generate artist commissions, community fellowships, computer simulations, and travelling exhibitions. The projects are:

● The Congruence Engine: Digital Tools for New Collections-Based Industrial Histories

● Our Heritage, Our Stories: Linking and searching community-generated digital content to develop the people’s national collection

● Transforming Collections: Reimagining Art, Nation and Heritage

● The Sloane Lab: Looking back to build future shared collections

● Unpath’d Waters: Marine and Maritime Collections in the UK

The investigation is the largest of its kind to be undertaken to date, anywhere in the world. It extends across the UK, involving 15 universities and 63 heritage collections and institutions of different scales, with over 120 individual researchers and collaborators.

Together, the Discovery Projects represent a vital step in the UK’s ambition to maintain leadership in cross-disciplinary research, both between different humanities disciplines and between the humanities and other fields. Towards a National Collection will set a global standard for other countries building their own collections, enhancing collaboration between the UK’s renowned heritage and national collections worldwide.

Archives Hub and the Transforming Collections: Reimagining Art, Nation and Heritage project

The Archives Hub at Jisc will be working with fellow project partners:

- Tate

- Arts Council Collection

- Art Fund

- Art UK

- Birmingham Museums Trust

- British Council Collection

- Contemporary Art Society

- Glasgow Museums

- Iniva (Institute of International Visual Art)

- Manchester Art Gallery

- Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art

- National Museums Liverpool

- Van Abbemuseum (NL)

- Wellcome Collection

The Principal investigator for Transforming Collections: Reimagining Art, Nation and Heritage project is Professor susan pui san lok, University of the Arts London.

More than twenty years after Stuart Hall posed the question, ‘Whose heritage?’, Hall’s call for the critical transformation and reimagining of heritage and nation remains as urgent as ever. This project is driven by the provocation that a national collection cannot be imagined without addressing structural inequalities in the arts, engaging debates around contested heritage, and revealing contentious histories imbued in objects.

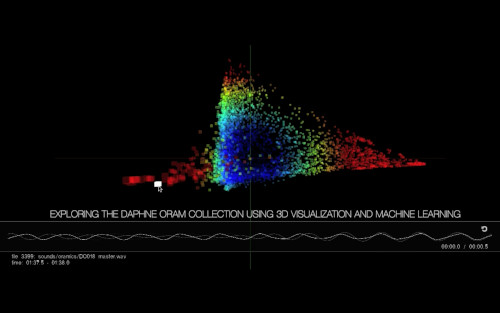

Transforming Collections aims to enable cross-search of collections, surface patterns of bias, uncover hidden connections, and open up new interpretative frames and ‘potential histories’ (Azoulay, 2019) of art, nation and heritage. It will combine critical art historical and museological research with participatory machine learning design, and embed creative activations of interactive machine learning in the form of artist commissions.

Among the aims of this project are to surface suppressed histories, amplify marginalized voices, and re-evaluate artists and artworks ignored or side-lined by dominant narratives; and to begin to imagine a distributed yet connected evolving ‘national collection’ that builds on and enriches existing knowledge, with multiple and multivocal narratives.

The role of the Archives Hub will centre around:

- Disseminating project aims, developments and outcomes to our contributors, through our communication channels and our cataloguing workshops, to encourage a wide range of archives to engage with these issues.

- Working with the Creative Computing Institute, at the University of the Arts London, to integrate the Machine Learning (ML) processing into the Archives Hub data processing workflows, so that it can benefit for over 350 institutions, including public art institutions.

- Providing expertise from over 20 years of running an archival aggregator and working with a whole range of UK archive repositories, particularly around sustainability and the challenges of working with archival metadata.