This post is based on a report published by OCLC Research, Single Search: The Quest for the Holy Grail (Leah Prescott and Ricky Erway, 2011).

It is less than ideal when users can benefit from a single search option for resources across the internet, but within an institution they are presented with a range of search systems for different services and resources. A single search obviously allows researchers to search across the organisation’s resources; it may also give a sense of the rich resources of an organisation and may provide a motivation to build upon them.

The OCLC report is based upon discussions with nine organisations that have implemented single search. There are certainly substantial challenges, not least the resources required and the need for effective collaboration across an institution. But it is clear that single search, if it is provided effectively, will help researchers and will help to harmonize collections management.

Single search needs to simplify rather than complicate the user experience, and sometimes the challenges this poses are not addressed and a single search ends up being a frustrating or confusing experience. We know that some users find navigating archival hierarchical descriptions confusing; adding library and museum items to this increases the challenge. Different collections may be catalogued very differently and to different levels of granularity, so presenting a coherent list of results is not easy. Added to this, many institutions now have digital collections, but only a part of their resources are digitised and so there is a need to indicate clearly what is digital (what can be accessed digitally) and what requires a visit to the institution.

Single search needs to simplify rather than complicate the user experience, and sometimes the challenges this poses are not addressed and a single search ends up being a frustrating or confusing experience. We know that some users find navigating archival hierarchical descriptions confusing; adding library and museum items to this increases the challenge. Different collections may be catalogued very differently and to different levels of granularity, so presenting a coherent list of results is not easy. Added to this, many institutions now have digital collections, but only a part of their resources are digitised and so there is a need to indicate clearly what is digital (what can be accessed digitally) and what requires a visit to the institution.

The OCLC report refers to single search having the ability to ‘fundamentally change how an institution identifies itself’. Maybe if the single search represents a large part of the resources of an institution this is true; it is not likely to be the case in a university, where the collections are only a small part of the university’s business. Single search may enable curators, archivists and librarians themselves to get a more coherent view of the collections. This could be a useful advantage, as we know that often curators in charge of one collection or subject area do not necessarily have a good understanding of the whole. It may encourage a more efficient and streamlined approach to collections management.

Amongst the nine institutions that formed part of the OCLC discussions, some did have a mandate to create single search, but even with this kind of directive, there is a need for senior managers to provide the resources required and ensure that it is made a priority. In addition, the isssue of individual motivation is significant. I think this is a fascinating area that is sometimes overlooked: The extent to which the staff involved are motivated to work together and to achieve a vision must have a substantial impact on the outcome. What sort of role to ‘champions’ play? How important are they? Does it come down to individuals with intellectual curiosity and the willingness to learning new skills and change working habits? Is it important for the institution to foster this kind of attitude in order to ensure that innovations like single search are likely to work? One of the institutions in the OCLC report referred to the staff that had been selected to work on a single search as being selected for their ‘interest, skills and capacity to work on the program’. I have certainly come across colleagues who are frustrated by a lack of co-operation from other staff, which can significantly hamper any kind of innovative changes to metadata creation and cross-searching.

I think that attitudes are key to success in a project like this, where working practices may have to change and habits may need to be broken. It reminds me of that great YouTube video of the lone dancer who is joined by just one person – one is a crazy lone dancer, and others tend to try to ignore him/her; but once just one person joins in you have a group, and once you have two, then you’re more likely to get three, then four, and then the group builds up to the extent where those who are reluctant to join in anything a bit new or different, where they might embarrass themselves, end up joining in because not joining in becomes the exception rather than the rule. It’s a slightly different scenario but the point is similar.

The size of the institution is likely to have an impact. A small institution is often more agile, and getting buy-in may be easier, although there may be less resource to draw on. Maybe for a large organisation, trying to implement something that cuts through the departments and teams in a very horizontal way, like single search, is harder if the organisational structures remain the same. The priorities of the different departments involved may end up pulling against the project. It becomes all the more important to define the goals, get buy-in at the right levels, have clear and effective communication channels, and also find an effective way to keep the momentum and motivation going.

The OCLC report makes one observation which resonates very much with me: ‘It is important for the success of the project to have representation…from IT units, as weak motivation within the IT area of an organization has the power to paralyze such a project.’ The important thing here seems to be to ensure that the right people are included at the right stages in the project. IT should be brought in right at the outset and a real effort should be made to develop not only a common understanding but also a feeling of good will and strong motivation.

As the OCLC report states: ‘The reality of achieving an integrated access vision could mean overturning years or decades of institutional thinking, which has segmented collections management practice among the three different sectors of LAMs.’ Professionals within libraries, archives and museums have their own perspectives and values, and are often very caught up in their own long-standing practices. There may be good reason for this – often curators and archivists have had to fight over time to ensure their collections are properly looked after and catalogued. But a single search may call for a more compromised approach, and certainly it is likely to call for different thinking and finding new ways to represent the collections.

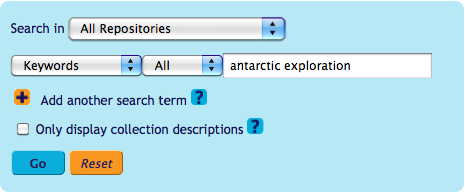

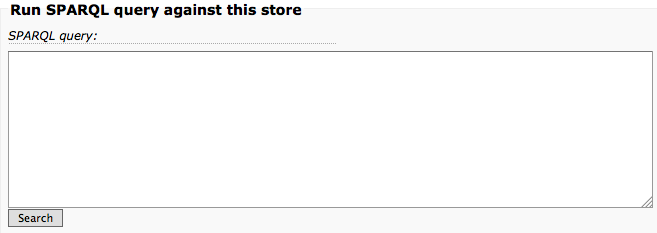

The ‘Technological Considerations’ section of the report is well worth reading, giving a short summary of some of the options. This is an area where the Archives Hub is very well aware of the pros and cons of different approaches. For an institution wanting to implement single search, there are a number of approaches: systems where you adopt batch export; systems where an API is used to pull the data in dynamically; a single system that replaces all the separate systems or multiple systems harvesting to a central repository; a federated search where each separate system is queried and results are brought back and presented to the user; a central index that is searched rather than the individual systems. All of these have pros and cons around things like flexibility, speed, currency and professional practices.

Of course, a further very important consideration will be digital assets, and the need to take a systematic approach here. Institutions may have Digital Asset Management Systems, but do these operate effectively with other collections sytems? Do digital assets exist in the different collections management systems? Are there shared metadata standards for digital assets?

Metadata Considerations present a whole new raft of challenges. I think that all to often those outside of the domains – maybe the managers who want to see single search and a more integrated approach – do not appreciate the substantial differences in approach between libraries, archives and museums. It is thought that because they all have something to do with that nebulous concept of ‘cultural heritage’ that they should all play together relatively easily. But each domain has built up its own world-view over many decades; the development of standards and best practice involves a great deal of hard work. It could be argued that finding ways to present catalogues or finding aids to users in a way that is as simple and straightforward as possible is not compatible with single search. It may be that single search, while seeking to provide an integrated approach, actually creates a more complex interface as a result of trying to integrate collection-based and hierarchical archival descriptions, item-based museum artifact descriptions and largely open access and usually non-unique library collections.

One of the biggest problems is that metadata is expensive to create. Automated metadata provides one solution but it is a very partial solution, especially for unique archival and musuem collections. Another challenge is that usually metadata has been created over long periods of time using a variety of systems, sometimes migrating from one system to another (often with patchy results). Metadata is messy, and yet standards lie at the heart of effective integration. But even standards are usually at different stages of evolution, and standards adopted by each of the domains do not necessarily harmonise very well.

One of the issues we have noticed on the Hub is the tendency for collections that are catalogued in great detail can overwhelm more summary descriptions. It can give the effect that those catalogued in more detail are more important. If you search on the Archives Hub relatively frequenly, you are likely to come across ‘University of Liverpool Staff Papers’ because they have been very thoroughly catalogued. There may be really good stuff in there, but should this one collection seem to be so much more important than so many others? Yet detailed cataloguing is surely a good thing?

There are also issues around vocabularies, and the tendency to implement multiple vocabularies within the same community. The Hub allows for any recognised vocabulary to be used for index temrsm but that does mean personal names, for example, entered using NCA Rules or AACR. You will inevitably end up with several different entries for the same name. The OCLC report refers to the need to harmonise metadata, trying to standardise terms, but I think that for us the way forward is generally to try to use the ever increasing sophistication of data processing tools to get round this problem, becuase we will never get 200 institutions to put things into the system in exactly the same way. Having said that, we are finding that as most of our contributors use our EAD Editor now, the descriptions are much more consistent and easier to integrate.

The OCLC report ends with some advice on the user interface, and one comment that I wholeheartedly agree with is the advice to hire or consult professional designers if you possibly can. Web presence is so important and Websites are often quite poorly designed. An ideal is to carry out user testing, but having done this ourselves, we know just how much time and effort it can take, and for many archives this is really quite a barrier. Even just testing with a small handful of users is very worthwhile. It’s amazing how much you find you have taken for granted that researchers will question. It’s good to see the importance of rights management emphasised and the need to clearly define access to content. This is becoming increasingly relevant, as data is republished, shared and recombined.

Single search is an important goal, not least because ‘the challenges inherent in this information divide ultimately expect researchers to compartmentalize their interests in a similar manner, rather than encouraging more multi-disciplinary approaches that focus on the research inqury (rather than the nature and custody of the resources).’ Our appoach has tended to suit our own professional outlooks; it should be geared towards what researchers want and need.