Machine Learning is a sub-set of Artificial Intelligence (AI). You might like to look at devopedia.org for a short introduction to Machine Learning (ML).

Machine Learning is a data-oriented technique that enables computers to learn from experience. Human experience comes from our interaction with the environment. For computers, experience is indirect. It’s based on data collected from the world, data about the world.

Definition of Machine Learning from devopedia.org

The idea of this and subsequent blog posts is to look at machine learning from a specifically archival point of view as well as update you on our Labs project, Images and Machine Learning. We hope that our blog posts help archivists and other information professionals within the archival or cultural heritage domain to better understand ML and how it might be used.

AI can be used for many areas of learning and research. Chatbots have been trialled at some institutions, for example, ‘Ada’ at Bolton College has generally been well received. AI can be useful for aspects of website usability and accessibility, or helping students to choose the right university degree. The Jisc National Centre for AI site has more information on how AI can add value for education and learning.

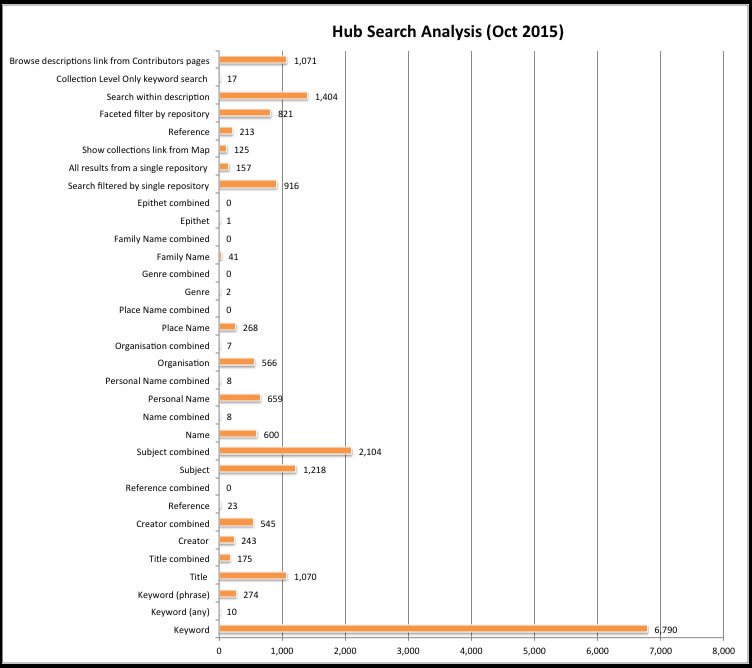

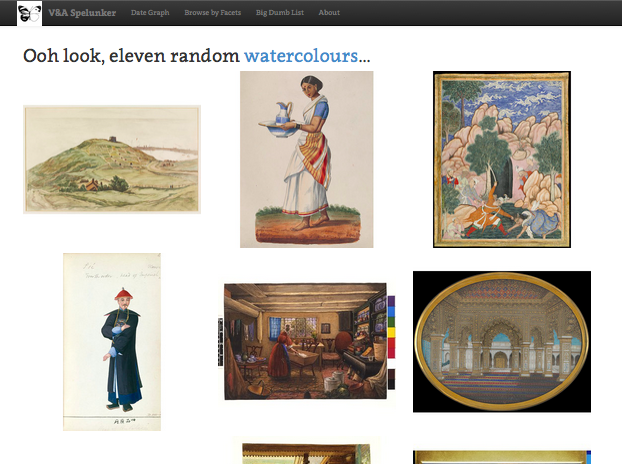

At the Archives Hub we are particularly focussed on looking at Machine Learning from the point of view of archival catalogues and digital content, to aid discoverability, and potentially to identify patterns and bias in cataloguing.

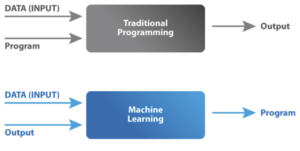

Machine Learning to aid discoverability can be carried out as supervised or unsupervised learning. Supervised learning may be the most reliable, producing the best results. It requires a set of data that contains both the inputs and the desired outputs. By ‘outputs’ we mean that the objective is provided by labelling some of the input data. This is often called training data. In a ‘traditional’ scenario, code is written to take input and create output; in machine learning, input and output is provided, and the part done by human code is instead done by machine algorithms to create a model. This model is then used to derive outputs from further inputs.

So, for example, taking the Vickers instruments collection from the Borthwick: https://dlib.york.ac.uk/yodl/app/collection/detail?id=york%3a796319&ref=browse. You may want to recognise optical instruments, for example, telescopes and microscopes. You could provide training data with a set of labelled images (output data) to create a model. You could then input additional images and see if the optical instruments are identified by the model.

Of course, the Borthwick may have catalogued these photographs already (in fact, they have been catalogued), so we know which are telescopes and which are micrometers or lenses or eye pieces. If you have a specialist collection, essentially focused on a subject, and the photographs are already labelled, then there may be less scope for improving discoverability for that collection by using machine learning. If the Borthwick had only catalogued a few boxes of photographs, they might consider using machine learning to label the remaining photographs. However, a big advantage is that the enhanced telescope recognising model can now be used on all the images from the Archives Hub to discover and label images containing telescopes from other collections. This is one of the great advantages of applying ML across the aggregated data of the Archives Hub. The results of machine learning are always going to be better with more training data, so ideally you would provide a large collection of labelled photographs in order to teach the algorithm. Archive collections may not always be at the kind of scale where this process is optimised. Providing good training data is potentially a very substantial task, and does require that the content is labelled. It is possible to use models that are already available without doing this training step, but the results are likely to be far less useful.

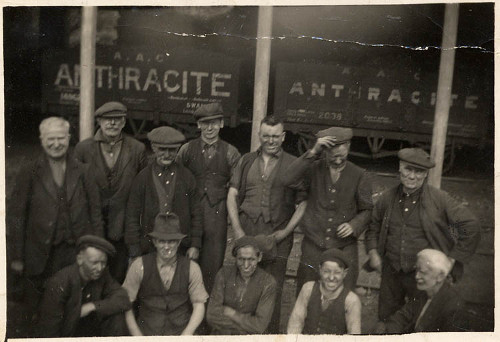

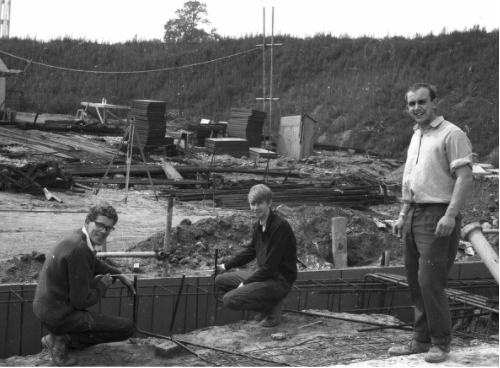

Another scenario that could lend itself to ML is a more varied collection, such as Borthwick’s University photograph collection. These have been catalogued, but there is potential to recognise various additional elements within the photographs.

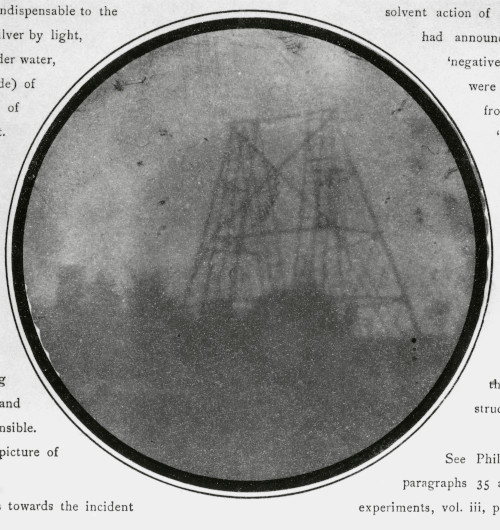

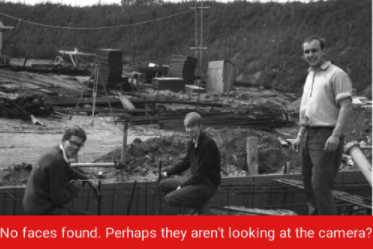

The above photograph has been labelled as a construction site. ML could recognise that there are people in the photograph, and this information could be added, so a researcher could then look for construction site with people. Recognising people in a photograph is something that many ML tools are able to do, having already been trained on this. However, archive collections are often composed of historic documents and old photographs that may not be as clear as modern documents. In addition, the models will probably have been trained with more current content. This is likely to be an issue for archives generally. For models to be effective, they need to have been trained with content that is similar to the content we want to catalogue.

The benefits of adding labels to photographs via ML to potentially enhance the catalogue and help with discoverability is going to depend upon a number of factors: how well the image is already catalogued, whether training data can be provided to improve the algorithm, how well ML can then pick out features that might be of use.

The drawings of fossil fish at the Geological Society are another example of a very subject specific collection. We put a few of these through some out-of-the-box ML tools. These tools have been pre-trained on large diverse datasets, but we have not done any additional training ourselves yet, so you could see them as generalists in recognising entities rather than specialists with any particular material or topic.

In this case the drawing has been tagged with ‘fossil’, which could be useful if you wanted to identify fossil drawings from a varied collection of drawings. It has also tagged this with archaeology and art, both of which could potentially be useful, again depending upon the context. The label of soil is a bit more problematic, and yet it is the one that has been added with 99.5% certainty. However, a bit of training to tell the algorithm that ‘soil’ is not correct may remove this tag from subsequent drawings.

This example illustrates the above point that a subject specific collection may be tagged with labels that are already provided in the catalogue description. It also shows that machine learning is unlikely to ever be perfectly accurate (although there are many claims it outperforms humans in a number of areas). It is very likely to add labels that are not correct. Ideally we would train the model to make less mistakes – though it is unlikely that all mistakes will be eliminated – so that does mean some level of manual review.

Tagging an image using ML may draw out features that would not necessarily be added to the catalogue – maybe they are not relevant to the repository’s main theme, and in the end, it is too time-consuming for cataloguers themselves to describe each photo in great detail as part of the cataloguing process.

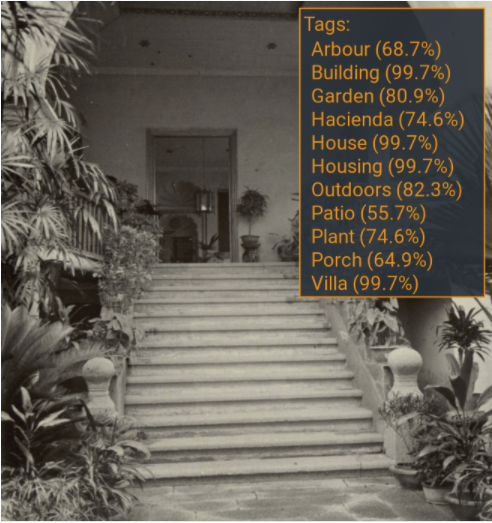

The above image is a simple one with not too much going on. It will be discoverable on the Queen’s website through a search for ‘china’ or ‘robert hart’ for example, but tagging could make it discoverable for those interested in plants or architectural features. Again, false positives could be a problem, so a key here is to think about levels of certainty and how to manage expectations.

As mentioned above, archival images are often difficult to interpret. They may be old and faded, and they may also represent features or items that an algorithm will not recognise.

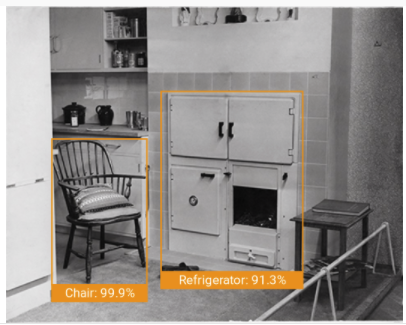

In the above example from Brighton Design Archives, the photograph is from a set made of an exhibition of 1947, Things In Their Home Setting. The AWS image Rekognition service has no problem with the chair, but it has confidently identified the oven as a refrigerator. This could probably be corrected by providing more training data, or giving feedback to improve the understanding of the algorithm and its knowledge of 1940’s kitchen furniture. But by the time you have given enough training data for the model to recognise a cooker from a fridge from a washing machine, it might have been easier simply to do the cataloguing manually.

Another option for machine learning is optical character recognition. This has been around for a while, but it has improved substantially as a result of the machine learning approach. Again, one of the challenges for archives is that many items within the collections are handwritten, faded, and generally not easily readable. So, can ML prove to be better with these items than previous OCR approaches?

A tool like Transkribus can potentially offer great benefits to archives, and is seen as a community-driven effort to create, gather and share training data. We hope to try out some experiments with it in the course of our project.

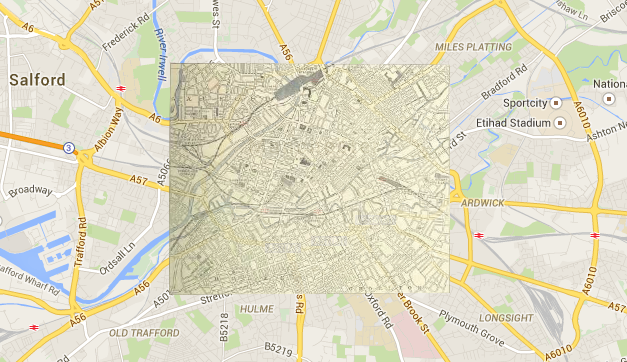

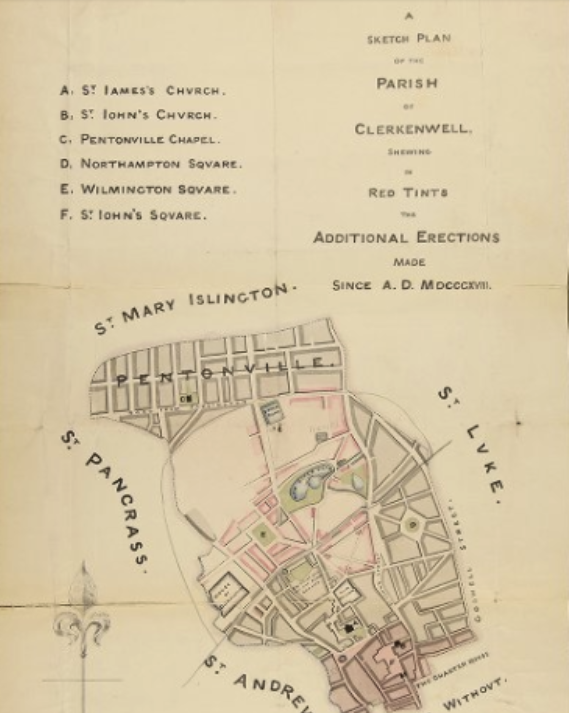

The above plan is from Lambeth Palace Library’s 19th century ecclesiastical maps. It can already be found searching for ‘clerkenwell’ or ‘st james parish’. But ML could potentially provide more searchable information.

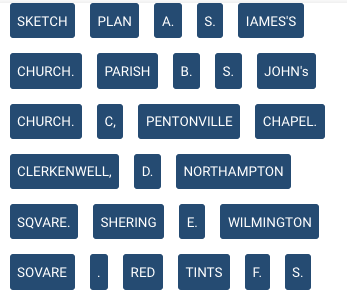

The words here are fairly clear, so the character recognition using the Microsoft Azure ML service is quite good. Obviously the formatting is an issue in terms of word order. ‘James’ is recognised as ‘Iames’ due to the style of writing. ‘Church’ is recognised despite the style looking like ‘Chvrch’ – this will be something the algorithm has learnt. This analysis could potentially be useful to add to the catalogue because an end user could then search for ‘pentonville chapel’ or ‘northampton square’ and find this plan.

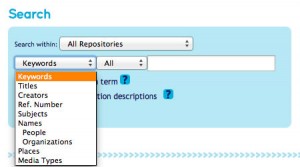

As well as looking at digital archives, we will be trying out examples with catalogue text. A great deal of archival cataloguing is legacy data, and archivists do not always have the time to catalogue to item level or to add index terms, which can substantially aid discoverability. So, it is tempting to look at ML as a means to substantially improve our catalogues. For example, to add to our index terms, which provide structured access points for end users searching for people, organisations, places and subjects.

In a traditional approach to adding subject terms to a catalogue, you might write rules. We have done this in our Names Project – we have written a whole load of rules in order to identify name, life dates, and additional data within index terms. We could have written even more rules – for example, to try to identify forename and surname. But it would be very difficult because the data does not present the elements of names consistently. We could potentially train an ML model with a load of names, tagging the parts of the name as forename, surname, dates, titles, epithets. But could an algorithm then successfully work out the parts of any subsequent names that we feed into it? It seems unlikely because there is no real consistency in how cataloguers input names. The algorithm might learn, for example, that a word, then a comma, then another word is surname, forename (Roberts, Elizabeth). But two words followed by a comma and another word could be surname + forename or forename + surname, (Vaughan Williams, Ralph; Gerald Finzi, composer). In this scenario, the best option may be to aim to use source data (e.g. the Virtual International Authority File) to compare our data to, rather than try to train a machine to learn patterns, when there really isn’t a model to provide the input.

We may find that analysing text within a catalogue offers more promise.

Here is an example from an administrative history of the British Linen Group, a collection held by Lloyds Banking Group. The entity recognition is pretty good – people’s names, organisations, dates, places, occupations and other entities can be picked out fairly successfully from catalogues. Of course that is only the first step; it is how to then use that information that is the main issue. You would not necessarily want to apply the terms as index terms for example, as they may not be what the collection is substantially about. But from the above example you could easily imagine tagging all the place names with a ‘place’ tag, so that a place search could find them. So, a general search for Stranraer would obviously find this catalogue entry, but if you could identify it as a place name it could be included in the more specific place name search.

With machine learning it is very difficult and sometimes impossible to understand exactly what is happening and why. By definition, the machine learns and modifies its output. Whilst you can provide training data to give inputs and desired outputs, machine learning will always be just that….a machine learning as it goes along, and not simply working through a programme that a human has written. Supervised learning provides for the most control over the outputs. Unsupervised learning, and deep learning, are where you have much less control (we’ll come onto those in later posts).

It is only by understanding the algorithms and what they are doing that you can set up your environment for the best results. But that is where things can get very complicated. We are going to try to run some experiments where we do prepare the data, but learning how to do this is a non-trivial task. Hence one of the questions we are asking is ‘is Machine Learning worth the effort required in order to improve archival discoverability?’ We hope to get at least some way along the road to answering that question.

There are, of course, other pressing questions, not least the issue of bias, and concerns about energy use with machine learning as well as how to preserve the processes and outputs of ML and document the decision making. But there could be big wins in terms of saving time that can then be dedicated to other tasks. The increasing volumes of data that we have to process may make this a necessity. We hope to touch upon some of these areas, but this is a fairly small scale project and Machine Learning it is one huge topic.