As archivists, we deal with ethical issues a good deal. But the ability to link disparate and diverse data sources opens up new challenges in this area, and I wanted to explore this a bit.

If you do a general search for ethics and data, top of the list comes health. An interesting example of data join-up is the move to link health data to census data, which could potentially highlight where health needs are not being met:

“Health services are required to demonstrate that they are meeting the needs of ethnic minority populations. This is difficult, because routine data on health rarely include reliable data on ethnicity. But data on ethnicity are included in census returns, and if health and census data for the same individuals can be linked, the problem might be solved.” (Ethnicity and the ethics of data linkage)

However, individuals who stated their ethnicity in census returns were not told that this might subsequently be linked with their health data. Should explicit informed consent be given? Given the potential benefits, is this a reasonable ask? It is certainly getting into hazardous terrain to ignore the principle of informed consent. In their book ‘Rethinking Informed Consent in Bioethics‘, Manson and O’Neill argue that informed consent cannot be fully specific or fully explicit. They argue for a distinctive approach where rights can be waived or set aside in controlled and specific ways.

This leads to a wider question, is fully explicit and specific informed consent actually achievable within the joined-up online world? A world where data travels across connections, is blended, re-mixed, re-purposed. A world where APIs allow data to be accessed and utilised for all sorts of purposes, and ‘open data’ has become a rallying cry. Is there a need to engage the public more fully in order to gain public confidence in what open data really means, and in order to debate what ‘informed consent’ is, and where it is really required?

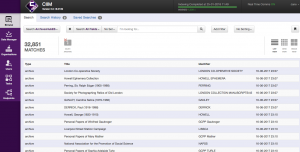

I am working on a project to create name records, and I am looking at bringing data sources together. Of course, this is hardly new. Wikipedia is the most well-known hub for biographical data. Anyone can add anything to a Wikipedia page (within some limits, and with some policing and editing by Wikipedia, but in essence it is an open database). Wikidata, which underlies Wikipedia, is about bringing sources together in an automated way. Projects within cultural heritage are also working on linked data approaches to create rich sources of information on people. SNAC has taken archival data from many different archive repositories and brought it together. A page for one person, such as Martin Luther-King provides a whole host of associations and links. These sources are not all individually checked and verified, because this kind of work has to be done algorithmically. However, there is a great deal of provenance information, so that all sources used are clear.

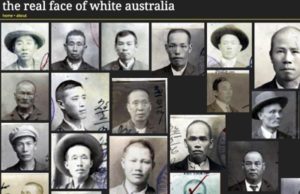

There are some amazing projects working to reveal hidden histories. Tim Sherratt has done some brilliant work with Australian records. Projects such as Invisible Australians, which aims to reveal hidden lives, using biographical information found in the records. He has helped to create some wonderful sites that reveal histories that have been marginalised. Tim talks about ‘hacking heritage’ and says: ‘By manipulating the contexts of cultural heritage collections we can start to see their limits and biases. By hacking heritage we can move beyond search interfaces and image galleries to develop an understanding of what’s missing.’ (Hacking heritage, blog post) He emphasises that access to indigenous cultural collections should be subject to community consultation and control. But what does community consultation and control really mean?

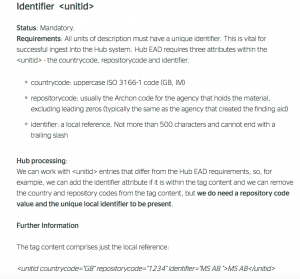

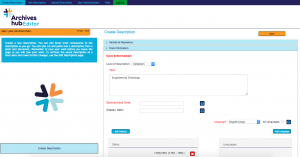

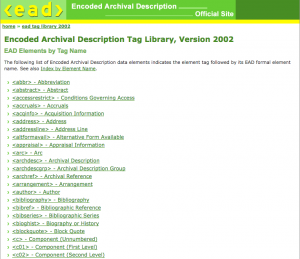

I have always been keen to work with the names in archival descriptions – archival creators and all the other people who are associated with a collection. They are listed in the catalogue (leastways the names that we can work with are listed – many names obviously aren’t included, but that’s another story), so they are already publicly declared. It is not a case of whether the name should be made public at all, or, at least, that decision has been made already by the cataloguer. But our plan is to take the names and bring them to the fore – to give them their own existence within our service. We are taking them out of the context of a single archive collection and putting them into a broader one. In so doing, we want to give the archive collections themselves more social context, we want to give more effective access to distributed historical records, and we also want to enable researchers to travel through connections to create their own narratives.

This may help to reveal things about our history and highlight the roles that people have played. It may bring people to the fore people who have been marginalised. Of course, it does not address the problem of biases and subjective approaches to accessions and cataloguing. But a joined-up approach may help us to see those biases and gaps; to understand more about the silent spaces.

Creating persistent identifiers and linking data reveals knowledge. It is temping to see that in simple terms as a good thing. But what about privacy and ethics? Even if someone is no longer living, there are still privacy issues, and many people represented in archives are alive.

Do individuals want to be persistently identified? What about if they change their identity? Do they want a pseudonym associated with their real name? They might have very good reasons for keeping their identity private. Persistent identification encourages openness and transparency, which can have real benefits, but it is not always benign. It is like any information – it can be used for good and bad purposes, and who is to say what is good and what is not? Obviously we have GDPR and the Data Protection Act, and these have a good deal to say about obligations, the value of historical research and the right to be forgotten. This is something we’ll need to take into account. But linked data principles are not so much about working with personal data as working with data that may not seem personal, but that can help to reveal things when linked with other sources of data.

GDPR supports the principle of transparency and the importance of people’s awareness and control over what happens to their personal data. Even if we are not creating and storing personal data, it seems important to engage with data protection and what this means. The challenge of how to think about data when it is part of an ever shifting and growing global data environment seems to me to be a huge one.

Certainly the horse has bolted to some degree with regards to joining up data. The Web lowered barriers considerably, and now we increasingly have structured data, so it is somewhat like one gigantic database. Finding things out about individuals is entirely feasible with or without something like a Names service created by the Archives Hub. We are not creating any new content, but creating this interface means we are consciously bringing data together, and obviously we want to be responsible, and respect people’s right to privacy. Clearly it is entirely impractical to try to get permission from all those living people who might be included. So, in the end, we are taking a degree of risk with privacy. Of course, we will un-publish on request, and engage with any feedback and concerns. But at present we are taking the view that the advantages and benefits outweigh the risks.

“Imagine being a sibling in a family that continually removes you from photos; tries its best to erase you…As you go through [the scrapbook] you see events where you know you were there, but you are still missing.” Lae’l Hughes-Watkins (University of Maryland) gave an impassioned and inspiring talk at DCDC 2019 about her experiences. She argued that archivists need to interrogate the reality that has been presented, and accept that our ideas of neutrality are misplaced. She wants a history that actively represents her – her history and culture, and experiences as a black woman in the USA. She related moving stories of people with amazing stories (and amazing archives) who distrust cultural institutions because they don’t feel included or represented.

This may seem a long way away from our small project to create name records, but in reality our project could be seen as one very small part of a move towards what Lae’l is talking about. Bringing descriptions together from across the UK together maybe helps us to play a small role in this – aiming to move towards documenting the full breadth of human experience. The archives that we cover may retain the biases and gaps for some time to come (probably for ever, given that documentary evidence tends to represent the powerful and the elite much more strongly), but by aggregating and creating connections with other sources, we help to paint a bigger picture. By creating name records we help to contextualise people, making it much easier to bring other lives and events into the picture. It is a move towards recognising the limitation of what is actually in the archive, and reaching out to take advantage of what is on the Web. In doing this through explicitly identifying people we do leave ourselves more open to the dangers of not respecting privacy or anonymity. When we plug fully into the Web, we become a part of its infinite possibilities, which is always going to be a revealing, exciting, uncontrollable and risky business. By allowing others to use this data in different ways, we open it up to diverse perspectives and uses.