On the Archives Hub we have plenty of name entries without dates. Here is an example of the name string ‘Elizabeth Roberts’ (picked entirely randomly) from several different contributors:

Richard and Elizabeth Roberts

Roberts, Elizabeth fl. 1931

Elizabeth Grace Roberts

Roberts, Elizabeth Grace

Elizabeth Roberts

Roberts, Elizabeth

ROBERTS, Elizabeth Grace

ROBERTS, Mrs Elizabeth Grace

The challenge we have is how to work this names like this. Let me modify this list into an imaginary but nonetheless realistic list of names that we might have on the Hub, just to provide a useful example (apologies to any Elizabeth Roberts’ out there):

Elizabeth Roberts 1790-1865

Elizabeth Roberts, 1901-1962

Elizabeth Roberts b 1932

Elizabeth Roberts fl. 1958

Elizabeth Roberts, artist

Elizabeth Roberts

Elizabeth Roberts

Elizabeth Roberts

How should we treat these names in the Archives Hub display? If we can make decisions about that, it may influence how we process the names.

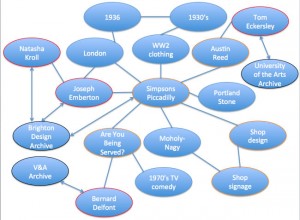

These names can be separated into two types (1) name strings that identify a person (2) name strings that don’t identify a person. This is a fundamental difference. It effectively creates two different things. One is an identifier for a person; one is simply a string that we can say is a name, but nothing more.

If we put two descriptions together because they are both a match to Elizabeth Roberts, 1790-1865, then we are stating that we think this is the same person, so the researcher can easily see collections and other information about them.

If we put two descriptions together that are both related to Elizabeth Roberts we are not doing the same thing. We are simply matching two strings.

Which of these names is an identifier? That depends upon levels of confidence, and that is why being able to set and modify levels of confidence is crucial.

Elizabeth Roberts 1790-1865 – this is enough to identify a person. In theory, there could be two people with the same life dates, but the chances are very low. So, we would bring together two entries and represented them on one name page.

Elizabeth Roberts b 1932 – Is a birth or death date enough? It allows for some measure of certainty with identity, and we would probably deem this to be enough to identify a person and match to another Elizabeth Roberts born in 1932, but it is not certain. If this Elizabeth Roberts was the creator, and she has several mentions of ‘art’, ‘artist’ and ‘painting’ in her biography, it is more likely that she is the same as Elizabeth Roberts, artist and might be useful to create a link, but would it be enough for a match?

Elizabeth Roberts fl 1931 – whilst a floruit date helps place the person in a time period, it is not enough to confidently identify a person.

Elizabeth Roberts, artist – occupation or other epithet enough is not usually enough to identify someone. If there is a biographical history, there is more information about the person, but this is not enough to be sure.

If we had an entry such as Elizabeth Roberts, Baroness Wood of Foxley (completely imaginary and just for the purposes of example), then the epithet is more helpful. We might decide that this identifies a person enough for a match with any other instances of Elizabeth Roberts with baroness wood and foxley in the name string.

If we had MacAlister, Sir Donald, 1st Baronet, physician and medical administrator then ‘1st baronet’ alongside the name should give enough confidence for a match with another entry for 1st Baronet.

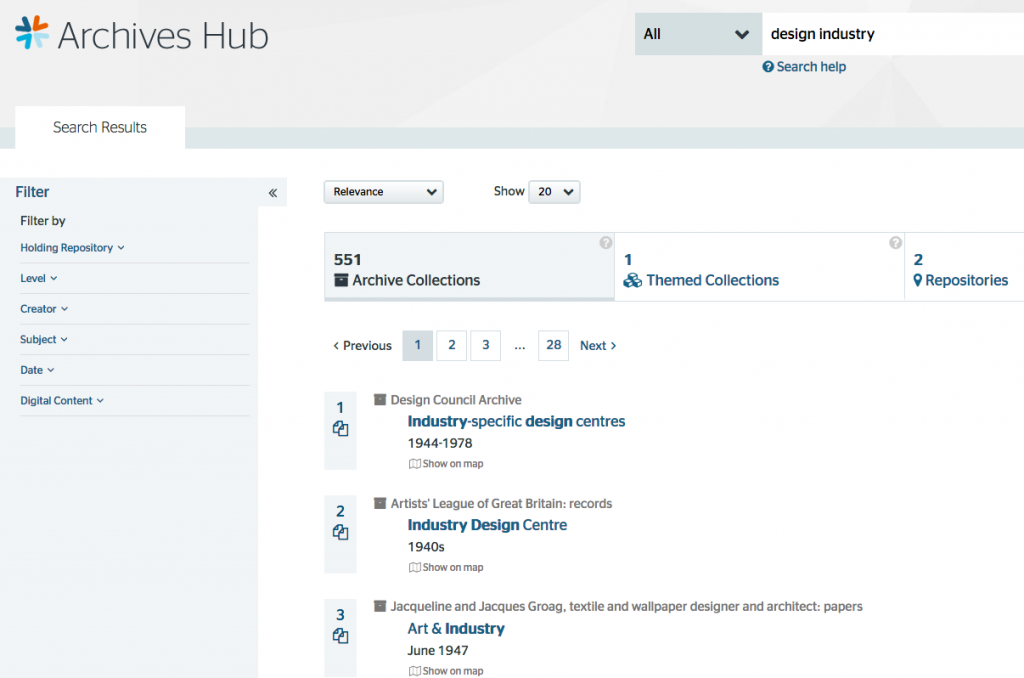

Display behaviour

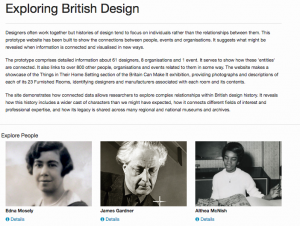

So, how might we reflect this in the display? It can be useful to think about the display and researcher requirements and expectations and work back from there to how we actually process the data.

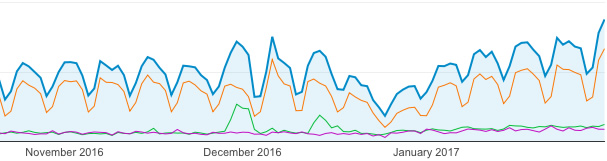

Firstly we might group two entries if they have the same date.

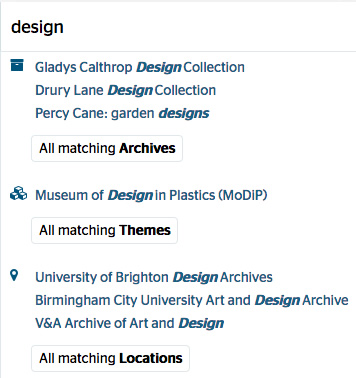

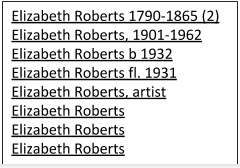

But this does not offer much benefit to the end user. They still see eight entries for this name string. So, we might bring together the entries that match exactly on the name string.

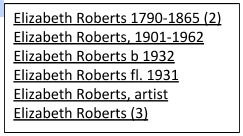

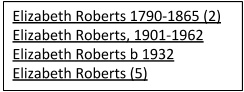

But there are still two entries that are essentially just name strings – the fl. and the ‘artist’ entry are essentially the same as those without any additional information in that they are name strings and they do not identify a person, so it makes sense to group all of these entries.

We now have a short set of entries. We can’t merge any more of them.

However, this does leave us with a problem. The end user is likely to assume that these all represent different people. That ‘Elizabeth Roberts’ is a different person from ‘Elizabeth Roberts 1901-1962’. The tricky thing is that she might be….and she might not be. It is likely that a user wanting Elizabeth Roberts with dates 1790-1865 would see the above list and click on the matching entry, not realising that the last three entries could also refer to the same person. We don’t want to exclude these from the researcher’s thinking without hinting that they may represent the same person.

We might give the list a heading that hints at the reality, such as ‘We have found the following matches:’. Maybe ‘matches’ would have a tool tip to say that the entries without dates could match the entries with dates. It is quite hard to even find a way to say this succinctly and clearly.

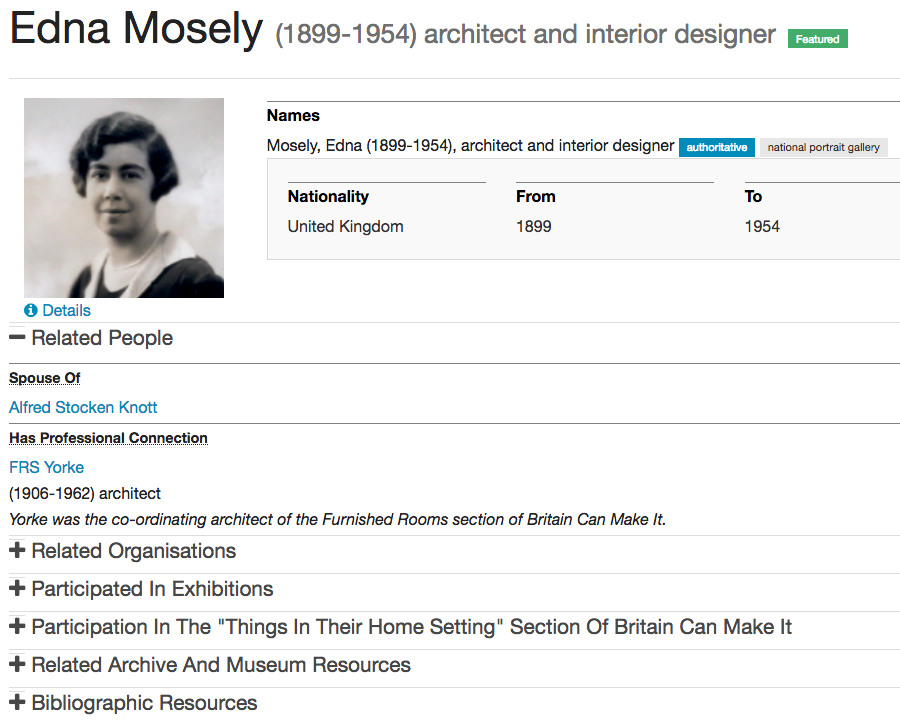

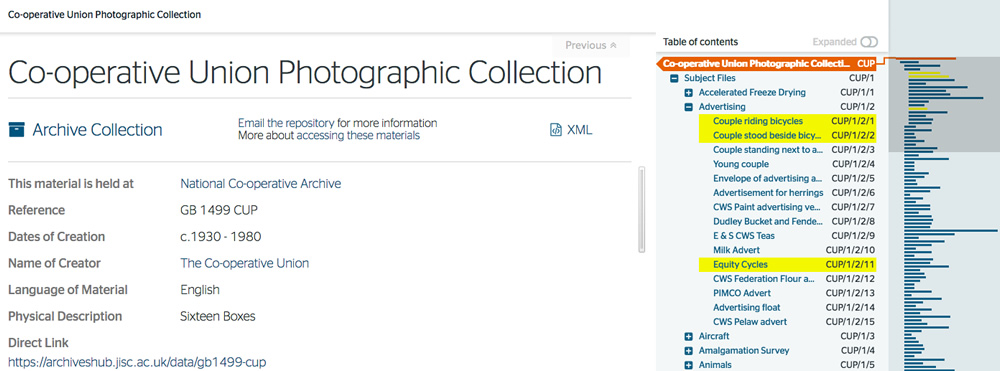

The identifiable names would link to name pages. We might provide information on the name pages to again emphasise that other Elizabeth Roberts entries could be of interest. We haven’t yet decided what would be best in terms of behaviour for the non-identifiable names – they might simply link to a description search – it does not make much sense to have a full name page for an unidentified person where all you have is one link to one archive description. We can’t provide links to any other resources for a non-identifiable name; unless we simply provide e.g. a Wikipedia lookup on the name. But again, we face the issue of misleading the end user; implying a ‘same as’ link when we do not have enough grounds to do that.

Names as creators

We may decide to treat creator names differently. Archival creator does have a significant meaning – it emphasises that this is a collections about that person or organisation (though even the nature of the about-ness is difficult to convey). But many users do not necessarily appreciate what an archival creator is, and many descriptions don’t provide biographical histories, so could this end up creating confusion? Also, in the end a creator name is far more likely to include life dates, so then they would have a full name page anyway. What would be the benefit of treating a creator name with no life dates and no biographical history differently from an index term and giving it a name page? You would just be linking to one archive, albeit ‘their’ archive.

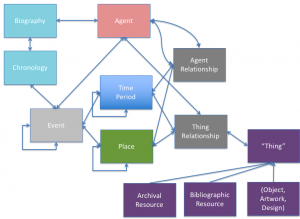

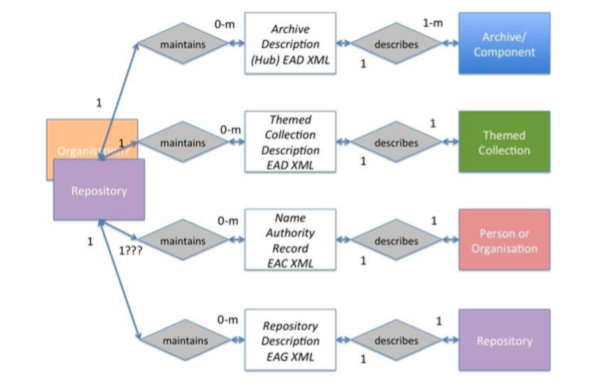

What about if a name string record, say the Elizabeth Roberts fl 1931, has been ingested as an EAC record, i.e. a name record that was created by one of our contributors? It is likely that name records will include a full date of birth, or at least a birth or death date, but this is not certain. Whilst we are not currently set up to take in EAC-CPF name records, we do plan to do this in the future. If the name is provided through an EAC record and they are a creator, they may have a detailed biography, and may have other useful information, such as a chronology, so a name page would be worthwhile.

This short analysis shows some of the problems with providing a name-based interface. We will undoubtedly encounter more thorny issues. The challenge, as is so often the case, is just as much about how to convey meaning to end users when they are not necessarily familiar with archival perspectives, as it is about how to process the data.

And we haven’t even got to thinking about Eliza Roberts or Lizzy Roberts…..