Archives Hub feature for May 2023

The beginnings of Archives of IT

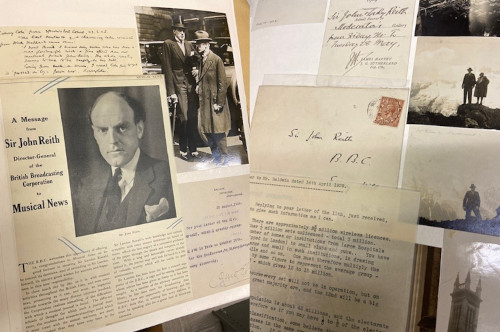

Archives of IT (AIT) began when entrepreneur Roger Graham saw the need to interview the founding generation of the IT Industry and save their stories for the future. Up to this point, heritage work was happening to save the history of computers, hardware and games but little was being done to preserve the social and oral history of the people behind the technology.

Archives of IT was registered as a Charitable Incorporated Organisation (CIO) in 2015, with the aims of educating the public on the history of IT, particularly through the provision of a digital archive, accessible at www.archivesit.org.uk. AIT is governed by trustees, chaired by communications specialist John Carrington, and has a small number of part time staff and a team of volunteers who manage the acquisition of materials, the website and the production of blogs and education resources.

Initially, the focus for interviews has been on early post-war pioneers of IT that were at the forefront of this new industry – the intention to save those stories before time ran out. However, as time has passed interviews have become more contemporary, capturing more current trends in the IT sector, and taking in diverse topics such as women in STEM, infra-red technology, cybersecurity, venture capitalists and wearable health devices.

Oral history interviews

Much has been achieved in AIT’s first seven years, including more than 220 oral history interviews recorded, transcribed, and uploaded to the website for people to view. The first interview was published on the website in 2017; David Potter CBE discusses his life in academia in computer simulation, then his move to the business world establishing Potter Scientific Instruments, or Psion. They invented the world’s first personal digital assistant – the Psion Organiser – in 1984 and advising Nokia in the 1990s as mobile telephone technology began to take off.

Other oral history collection highlights include:

- The first UK Professor of Informatics and a pioneer of early commercial computing Professor Frank Land

- The first female IT entrepreneur Dame Stephanie Shirley

- Lord Kenneth Baker, the first Minister for IT appointed by British PM Margaret Thatcher in 1981

- Software engineer Mandy Chessell CBE, IBM Master Inventor and first woman to be awarded the Silver Medal of the Royal Academy of Engineers

- Sir Clive Sinclair, inventor, and home computing pioneer

- Martha Lane-Fox, ‘dot.com bubble’ internet entrepreneur

- Merchant banker and IT investor Sir Kenneth Olisa

Education resources – Schools

As part of its charitable aims to contribute to IT education in the UK, AIT have produced primary school learning and careers resources for teachers in collaboration with The Institution of Engineering and Technology. Key Stage 1 and 2 lesson plans have been developed and are available to download on the website. Key Stage 3 and 4 careers advice to encourage pupils to consider a job in IT are also available.

A recent school competition to design a logo for FIFA World Cup 2026 was successful, with nearly 100 entries from UK Schools. This latest competition was linked to the national curriculum by encouraging schoolchildren to use technology purposefully to create, organise, store, manipulate and retrieve digital content to accomplish a given goal.

It also involved history by looking at events beyond living memory that are significant nationally or globally and art, to use drawing to develop and share their ideas, experiences and imaginations and develop a wide range of design techniques using colour, line, shape, form, and space.

Education resources – Research projects

AIT is working with several partners to produce research based on its collections. Published research can be read here on topics ranging from the post Second World War IT Industry to 60 years progress of women working in IT.

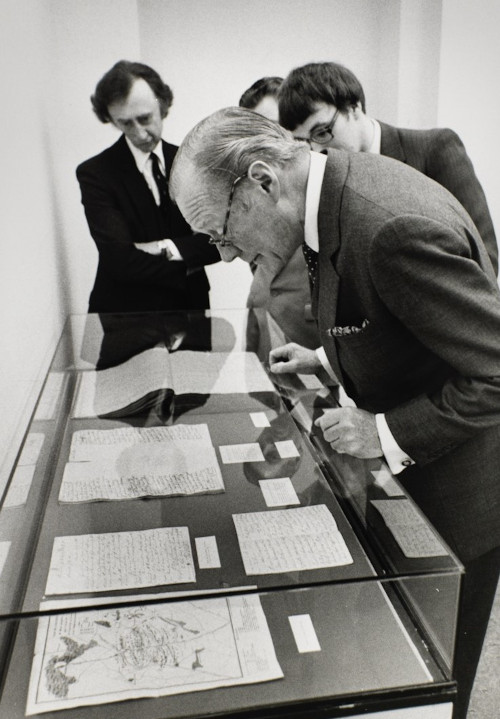

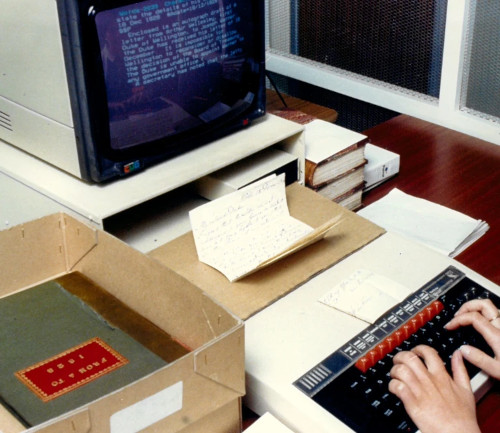

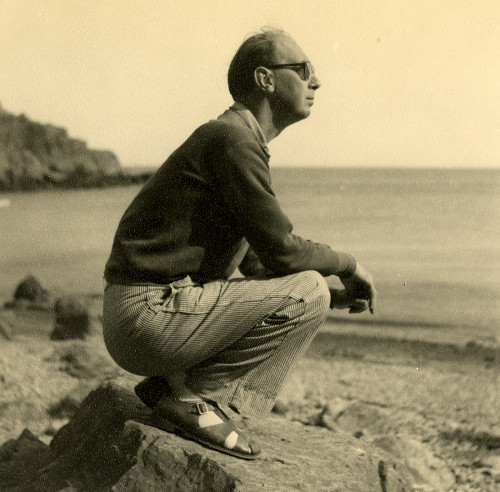

The most recent piece of research commissioned is by Dr Elisabeth Mori on the development of human-computer interaction over the past 70 years. Dr Mori will use existing AIT content and conduct new interviews to bring together the story of human computer interaction (HCI) in a unique and comprehensive way.

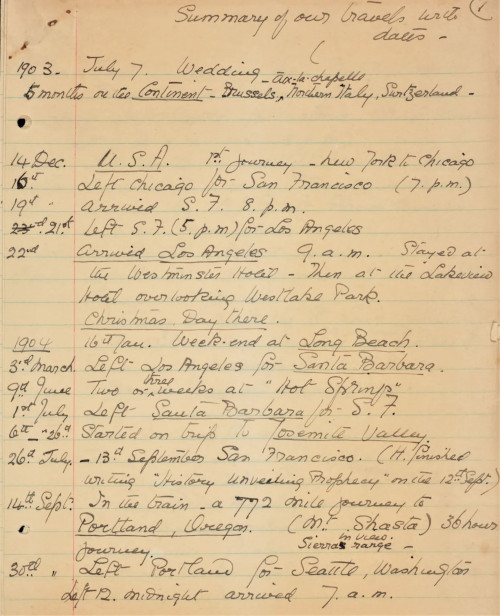

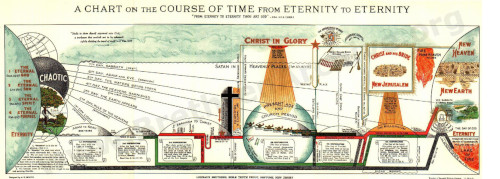

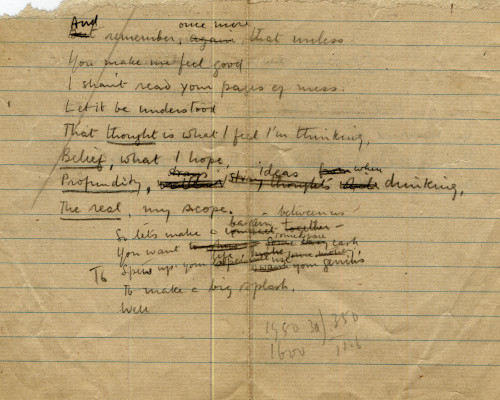

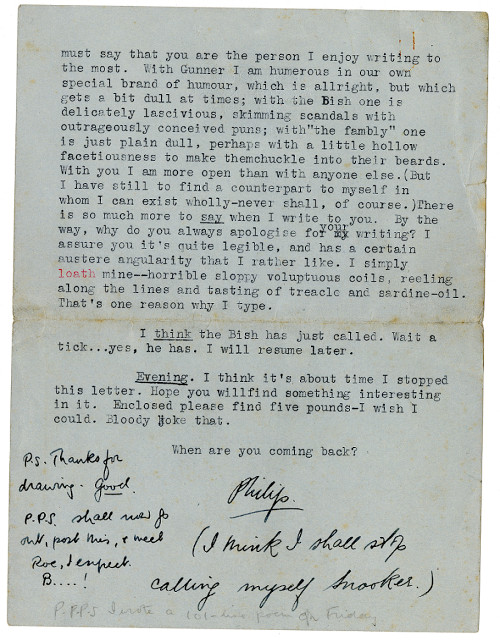

A small number of publications have been donated to us by supporters and interviewees, and digitised versions of them can be viewed on our website, alongside other databases and websites hosted independently by people involved in the early years of the IT industry, that may be of use to researchers browsing our website.

The Archives Hub

AIT is a new archive, and non-traditional in that it has no geographical location and is digital only. As it develops, AIT is focusing on improving discovery of its collections on the internet.

As part of these plans, in 2022 we contributed an online resource description to the Archives Hub. This description is intended as a guide to AIT’s website, and it is hoped its presence on the Hub will increase the website’s use by academics and university students. The aim is to contribute a multi-level description of AIT’s collections to the Hub soon.

Further information

- Dr Sam Blaxland’s article ‘The Archives of Information Technology: More Than Just Computers’ available at https://archivesit.org.uk/the-archives-of-information-technology-more-than-just-computers/.

- Watch our founder Roger Graham MBE talk about founding Archives of IT on our YouTube account https://youtu.be/q_W16jEcgGs

Stephanie Nield

Archivist, Archives of IT

Related

Archives of IT: Oral Histories of IT and tech, 2015 onwards (Online Resource description)

Photograph of Dr Elisabetta Mori by Armin Linke. All other images copyright AIT. Reproduced with the kind permission of the copyright holders.