Archives Hub feature for June 2020

Special Collections holds over 700 letters written by members of the Rossetti family. The collection includes letters from nearly all members of this storied family, with the bulk written by Dante Gabriel (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dante_Gabriel_Rossetti) and William Michael (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Michael_Rossetti), and a significant tranche from Christina Rossetti (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christina_Rossetti). The letters are only a fraction of the full Rossetti family correspondence, which can be found in libraries and archives across the world.

Many of the letters have been in Special Collections since the 1930s but were not catalogued in any detail. Some were represented by very brief index records, which did not convey the scope or context of the full collection, others were entirely uncatalogued. Although much of the Dante Gabriel and Christina Rossetti correspondence had been published in their respective Collected Letters ((The Correspondence of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, ed. William E. Fredeman, 2015 and The Letters of Christina Rossetti, https://rotunda.upress.virginia.edu/crossetti/), but the letters themselves remained inaccessible for research.

A 2019 project funded by the Strachey Trust enabled us to repackage and create item-level records for each letter in the collection. Catalogue records included basic ISAD(G) metadata, a brief synopsis of the letter’s contents, links to authority files for both sender and addressee and a reference for the published version of the letter, where one exists. The finished catalogue now describes the full extent of the Rossetti Collection at Leeds, ensuring that material is identifiable, accessible for research and secure in our holdings.

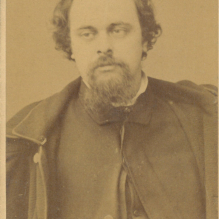

Cataloguing gave us fascinating insight into the lives of the Rossettis. The largest group of letters in the collection were written by Dante Gabriel Rossetti and cover both the beginning and end of his career. Early letters reveal a humorous correspondent. One, written from a deluged Kent, describes him sketching ‘with my umbrella tied over my head to my buttonhole – a position which you will oblige me by remembering, I expressly desired should be selected for my statue. (N.B. Trousers turned up.)’

These are in direct contrast to later letters to Theodore Watts-Dunton (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theodore_Watts-Dunton) who acted as Rossetti’s advisor. The volume and regularity of Rossetti’s letters to Watts-Dunton, their paranoia and requests for advice show Rossetti’s great dependence on his close friends in later years.

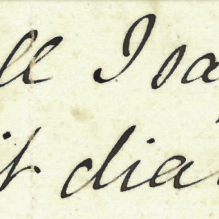

The collection includes 30 letters written by Christina Rossetti. Project work uncovered a previously unknown letter, written to her sister-in-law, Lucy Maddox Brown Rossetti (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucy_Madox_Brown). This brief letter gives Rossetti’s assessment of an unnamed poem: ‘The fact is I think it diabolical. Its degree of serene skill and finesse intensifies to me its horror…’

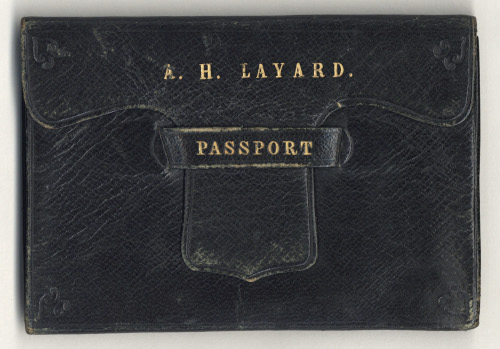

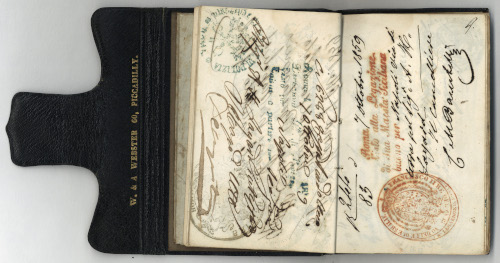

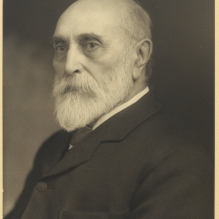

150 letters by William Michael Rossetti were also catalogued during this project, the majority of which are unpublished. His letters include a long series addressed to John Lucas Tupper (https://sculpture.gla.ac.uk/view/person.php?id=msib7_1220373335), a close associate and contributor to ‘The Germ’, the journal of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. The letters to Tupper, whose writing and career he promoted, highlight professional opportunities and networks of editors and journals available during this period. They give an interesting glimpse of the kind of life afforded to a literary Victorian gentleman employed by the Civil Service. During certain periods of his life, Rossetti travelled abroad, visiting the continent and even Australia. Having been robbed on one occasion in Italy, he discusses the advisability of carrying a pistol with Tupper, who travelled with him in 1869. Other letters cover wide-ranging topics, from discussions of Ruskin and Browning to the politics of the day, spiritualism, and lycanthropy.

Alongside revealing individual letters, the catalogue records now allow researchers to explore Rossetti family networks in some detail. A good example of this is correspondence relating to the artist Frederic Shields (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frederic_Shields), who was a regular subject of Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s letters to Watts-Dunton. Later letters from William Michael Rossetti to Shields describe the hours before his brother’s death with great tenderness, passing on a last message to Shields. Subsequent letters from Christina Rossetti are concerned with Shields’ work on a memorial for Dante Gabriel Rossetti. These intertwined relationships would not be easily discoverable from published letters alone but can be usefully explored through this catalogue.

Cataloguing also gave us the chance to research the provenance of groups of letters in the collection. This revealed connections between material previously considered separate: the Swinburne manuscript collection (https://explore.library.leeds.ac.uk/special-collections-explore/8607) and substantial correspondence relating to Swinburne and Watts-Dunton (including Rossetti correspondence) were all acquired from the same source, Watts-Dunton’s estate. These letters and manuscripts had historically been treated as distinct collections, and the connections between them were not clear from catalogue records.

Cataloguing work on this small collection has emphasised the many levels of interconnectedness in which archives exist. Letters can show relationships between individuals, collections of letters show their wider networks, and collections themselves speak to other material both within a repository and in many other locations across the world.

The Rossetti family letters collection is now available for research (https://explore.library.leeds.ac.uk/special-collections-explore/7436). This project would not have been possible without the support of the Strachey Trust, and Special Collections is grateful to it for its generosity in funding work on this significant collection.

Sarah Prescott

Literary Archivist

University of Leeds Special Collections

Related

Rossetti Family correspondence, 1843-1909

Browse all University of Leeds Special Collections descriptions on the Archives Hub

Explore more collections relating to the Rossetti family on the Archives Hub

Previous features on University of Leeds Special Collections:

“Gather them in” – the musical treasures of W.T. Freemantle

Sentimental Journey: a focus on travel in the archives

All images copyright University of Leeds Special Collections and National Portrait Gallery, London. Reproduced with the kind permission of the copyright holders.