Back in 2014 the Archives Hub joined forces with The University of Brighton Design Archives for an exciting new project, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, ‘Exploring British Design’ (EBD).

The project explored Britain’s design history by connecting design-related content in different archives, with the aim of giving researchers the freedom to explore around and within archives.

You can read a number of blog posts on the project, and there is also a video introducing the EBD website on You Tube, but in this post I wanted to set out how we have learned from the project and how it has informed the development of the new Archives Hub.

Unfortunately, we may not be able to maintain the website longer term, and so it seemed timely to reflect on how the principles used in this project are being taken forward.

Modelling the Data

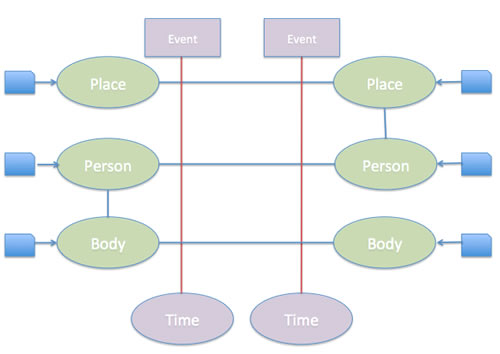

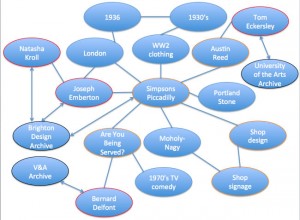

A key component of EBD was our move away from the traditional approach of putting the archive collection at the centre of the user experience. Instead, we wanted to reflect the richness of the content – the people, organisations, places, subjects, events that a collection represents.

We had many discussions and filled many pieces of paper with ideas about how this might work.

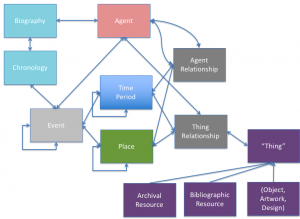

We then took these ideas and translated them into our basic model.

Archives are represented on our model as one aspect of the whole. They are a resource to be referenced, as are bibliographic resources and objects. They relate to the whole – to agents, time periods, places and events. This essentially puts them into a whole range of contexts, which can expand as the data grows.

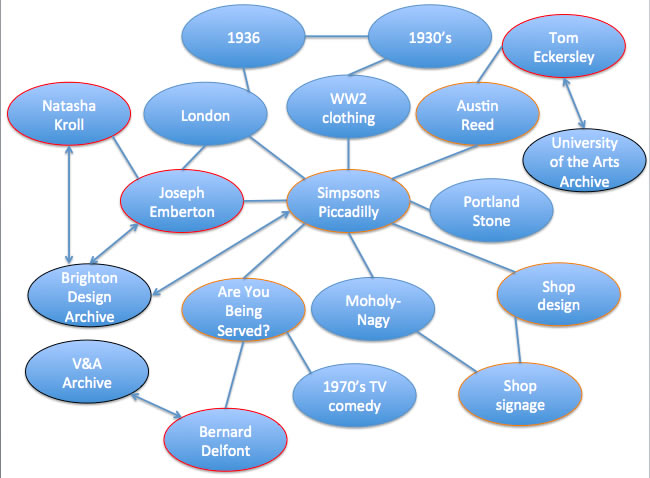

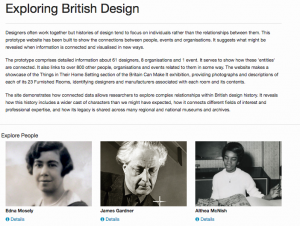

The Exploring British Design website was one way to reflect the inter-connected model that we created.

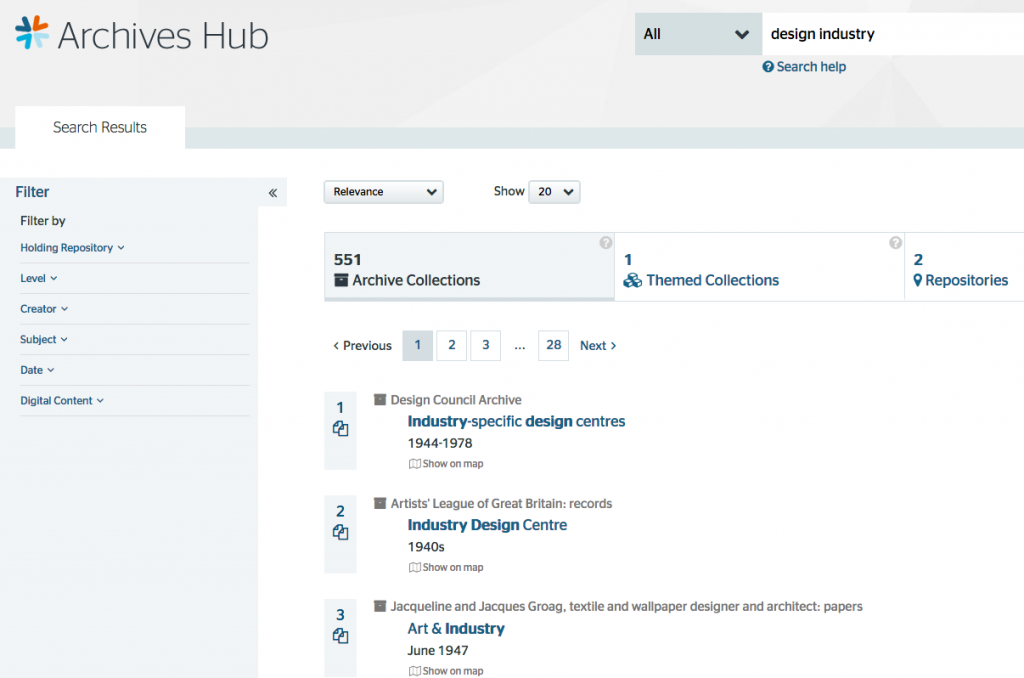

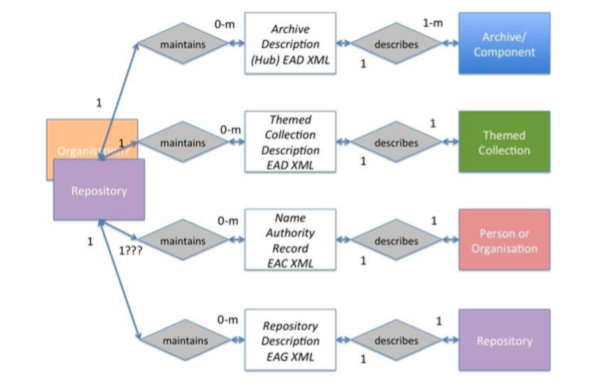

We have taken the principles of this approach with the new Archives Hub architecture and website, which was launched back in December 2016. Whilst the archive collection description stays very much in the forefront of the users’ experience, we have introduced additional tabs to represent themed collections and repositories. All three of these sources of information are, in a data and processing sense, treated equally. The user searches the Hub and the search runs across these three data sources. The model allows us to be flexible with how we present the data, so we could also try different interfaces in future, maybe foregrounding images, or events.

Names

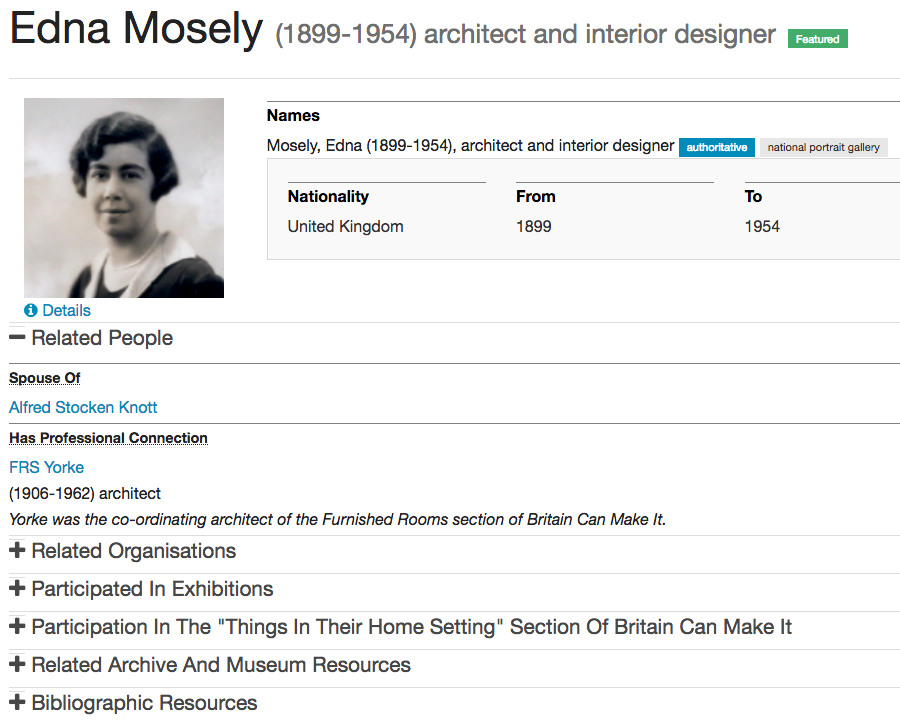

The EBD project had a particular focus on people. We opted to combine machine methods of data extraction – data taken partly from our already existent archive descriptions as well as from other external sources – with manual methods, to create rich records about designers. This manual approach is not sustainable for a large-scale service like the Archives Hub, but it shows what is possible in terms of creating more context and connectivity.

We wanted to indicate that well-structured data allows a great deal more flexibility in presentation. In this case the ‘Archive and Museum Resources’ are one link in the list of resources about or related to the individual. We could have come up with other ways to present the information, given how it was structured.

We are intending to introduce names pages to the Archives Hub, which will then more clearly echo the EBD approach. They will largely have been created through automated processes, as we needed to create them at scale. They will generally be quite brief, without the ideal structure or depth, but the principle remains that we can then link from a person page to a host of related resources. The Hub website will have a new tab for ‘Names’ and end users will be able to run searches that take in collections, themes, repositories, people and organisations.

The EBD project allowed us to explore standards used for the creation of names data. It was our first experience of using Encoded Archival Context (Corporate Bodies, Persons and Families) (EAC-CPF), so we could start to see what we could do with it, as well as discover some of the shortcomings of the standard, as our data went beyond what is supported. For example, we wanted to link images to people and events but this was not covered by the standard. It was useful to have this preliminary exploration of it, and what it can – and can’t – do, as we look to adopt it for names within the Archives Hub.

Structured Data

One of the things the project did reinforce for me was the importance of indexing. On the Archives Hub we have always recommended indexing, but we have had mixed reactions from archivists, some feeling that it is less useful than detailed narrative, some saying that it is not needed ‘now we have Google’, some simply saying they don’t have time.

Indexing has many advantages, some of which I’ve touched on in various blog posts – and one at the top of the list, is that it brings the advantages of structured data. A name in a narrative can, in theory, be pulled out and utilised as a point of connectivity, but a name as an index term tends to be a great deal easier to work with: it is identified as a name, it usually has structured surname, forename content, it usually includes life dates and may include titles and epithets to help unambiguously identify an individual.

EBD was all about structured data, and we gave ourselves the luxury of adding to the data by hand, creating rich structured records about designers. This was partly to demonstrate what could be done in an interface, but we were well aware that it would be problematic to create records of that level of detail at scale. However, as we start to grapple with expanding name records in the Archives Hub, we have EBD as a reference point. It has helped us to think more about approaches and priorities when creating name records. If we were to create an EAC Editor (similar to our EAD Editor) we would think carefully about how to facilitate creating relationships. For example, the type of relationship – should there be a controlled list of relationship types? e.g. ‘worked with, collaborated with, had professional connection with, influenced by, spouse of’ – these are some of the relationships we used in EBD, after much discussion about how best to approach this. Or would it be more practical to stick to ‘associated with’ (i.e. not defined), which is easier, but far less useful to a researcher. Could we have both? How would one combine them in an interface? Another example – the potential to create timelines. If we wanted to provide end users with timelines, we would need to focus on time-bound events. There are many issues to consider here, not least of which is how comprehensive the timeline would be.

The vexed question of how to combine data from name descriptions created by several institutions is not something we really dealt with in EBD, but that will be one of the biggest challenges for us in aiming to implement name data on the Archives Hub.

The level of granularity that you decide upon has massive implications for complexity, resources and benefits. The more granular the data, the more potential for researchers to be able to drill down into lives, events, locations, etc. So including life dates allows for a search for designers from 1946; including places of education allows for exploring possible connections through education, but adding dates of education allows for a more specific focus still.

Explaining our approach

One thing that struck me about this project was that it was harder than I had anticipated to convey to people what we were trying to achieve and what we could achieve. I tended to find that showing the website raised a number of expectations that I knew would be difficult to fulfill, and if I’m being honest, I sometimes felt rather frustrated at the lack of recognition of what we had achieved – it’s really not easy to combine, process and present different data sources! It is ironic that the more we press forwards with new functionality, and try to push the boundaries of what we do, the more it seems that people ask for developments that are beyond that! You can try to modify expectations by getting deep down and technical with the challenges involved in aggregating and enhancing data created over time, by different people, in different environments (we worked with CSV data, EAC-CPF data, RDF and geodata for example), with different perspectives and priorities. But detailed explanations of technical challenges are not going to work for most audiences. End users see and make an assessment of the website; they shouldn’t really need to be aware of what is going on behind the scenes.

Originally, in our project specification, we asked the question: “How can we encourage researchers, archive and museum professionals, and the public, to apprehend an integrated and extended rather than collection-specific sense of Britain’s design history?” Whilst we did not go as far to answer this question as we had hoped, the work that we did made me feel that it might be harder than I had envisaged. People are very used to the traditional catalogues and other finding aids that are out there, and it creates a certain (possibly unconscious) mindset. I know this too well, because, as an archivist, I have had to adjust my own thinking to see data in a different way and appreciate that traditional approaches to cataloguing and discoverability are not always suited to the digital online age.

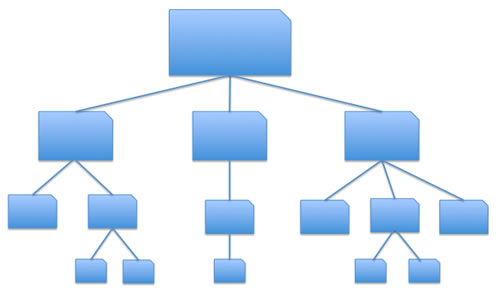

Data Model

The hierarchical approach to data is very embedded among archivists, and this is what people are used to being presented with. Unless archivists catalogue in a different way, providing more structured information about entities (names, places, etc) then actually presenting things in a more connected way is hard.

A more inter-connected model, which eschews linear hierarchy in favour of fluid entity relationships, and allows for a more flexible approach with the front-end interface to the data relies upon the quality, structure and consistency of the data. If we don’t have place names at all we can’t provide a search by place. If we don’t have place names that are unambiguously identified (i.e. not just ‘Cambridge’) then we can provide a search by place, but a researcher will be presented with all places called Cambridge, anywhere in the world (including the US, Australia and Jamaica).

The new Archives Hub was designed on the basis of a model that allows for entities to be introduced and new connections made.

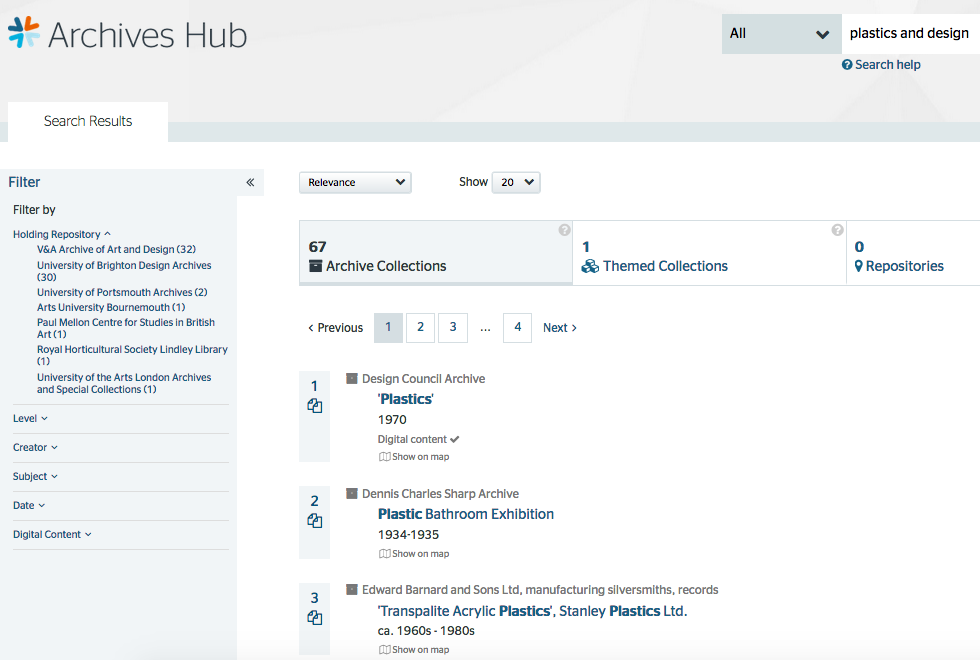

So, the tabs that the end user sees in the interface can be modified and extended over time. Searches can be run across all entities; it is not solely about retrieving descriptions of archives. This approach allows for researchers to find e.g. repositories that are significantly about ‘design’ or repositories that are located in London. It allows us to introduce Themed Collections as a separate type of description, so a student doing a project on ‘plastics’ would discover the Museum of Design in Plastics as a resource alongside archive collections at repositories including Brighton Design Archives, the V&A and the Paul Mellon Centre.

Website Maintenance

One of the things I’ve learnt from this project is that you need to factor in the ongoing costs and effort of maintaining a project website. The EBD website is quite sophisticated, which means there are substantial technical dependencies, and we ended up running into issues with security, upgrades and compatibility of software, issues that are par for the course for a website but nonetheless need dealing with promptly. Maybe we should have factored this in more than we did, as we know the systems administration required for the Archives Hub is no small thing, but when you are in the throws of a project your focus is on the objectives and final output more than the ongoing issues. We cannot maintain a site long-term that is not being regularly used. EBD does not get the level of use that would justify the resources we would have to put into it on an ongoing basis.

Conclusion

When we were creating the model for the Archives Hub, we thought as much about flexibility and future potential as anything else. This is one thing that we have learnt from running the Hub for 25 years and from projects like Exploring British Design. You need to plan for potential developments in order to start to work with cataloguers, to get the data into the shape that you need it to be. We wanted to be able to introduce additional entities, so that we could have names, places, languages, images, or any other entities as ‘first class citizens‘ of the Hub. We wanted to be able to enhance the end user’s ability to take different paths, and locate relevant archives through different avenues of exploration.

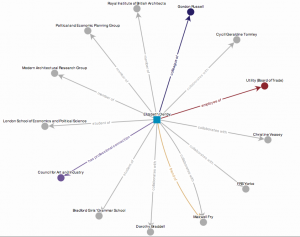

We need to temper our ambitions for the Hub with the realities of cataloguing, aggregation and resources available, and we need as much information as we can get about what researchers really want; but this is why it is so important to encompass potential as well as current functionality. We may not be able to introduce everything we have envisioned or that users ask for right now; but it is important to understand the vital link between approaches to cataloguing, adherence to data standards, and front end functionality. We created visualisations for EBD and we would love to do this for the Hub, but it was not an easy thing to do, and so we would need to consider what the data allows, the software options available, whether the technical requirements are sustainable over time, and the effectiveness of the end result for the researcher.

When we demonstrated the visualisations in EBD, they had the wow factor that was arguably lacking in the main text-based site, but for serious researchers the wow factor is a great deal less important that the breadth and depth of the content, and that requires a model that is fundamentally rigorous, sustainable over time and realistic in terms of the data that you have to work with.