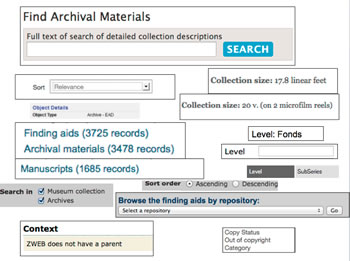

We have recently been reprocessing the Archives Hub data, transforming it into RDF based Linked Data, and as part of this we have been working on names matching. For Linked Data, creating links to external data sources is key – it is what defines Linked Data and gives the opportunities, potentially, for researchers to explore topics across data sources.

This names matching work has big implications for archives. I have already talked extensively in the Hub Blog about the importance of structured data, which is more effectively machine processable. For archival descriptions, we have a huge opportunity to link to all sorts of useful data sources, and one of the key means to link our data is through personal names. To do this effectively, we need names to be structured, and this is one of the reasons why the Hub practice of structuring names by separating out surname, forename, dates, titles and descriptive information (epithets) is so useful. We do this structuring even though EAD (the recognised XML standard for archives) doesn’t actually allow for it. We took the decision that the advantages would outweigh the disadvantages of a non-standard approach (and we can export the data without this additional markup, so really there is no disadvantage).

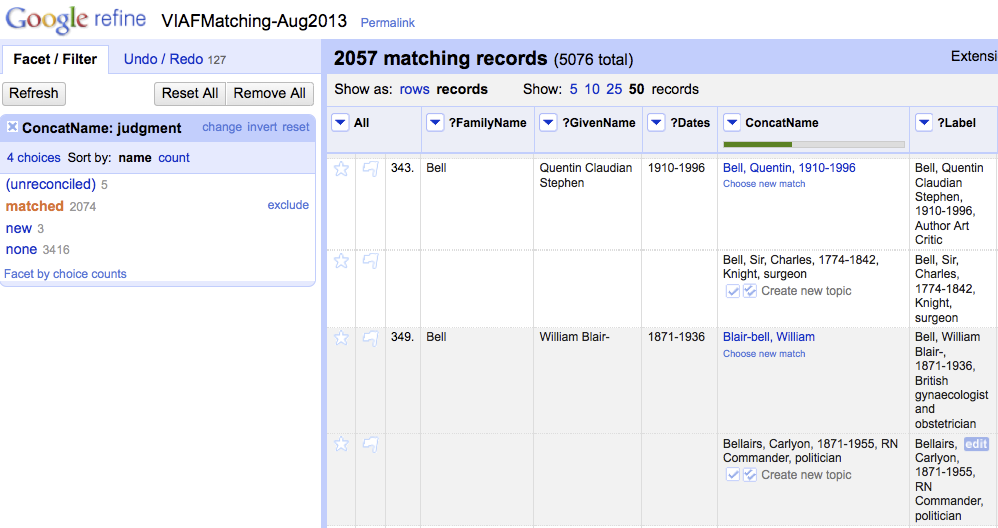

We have been working on the matching, using the freely available Open Refine data processing tool with the VIAF reconciliation service developed by Roderick Page. Freely available tools like this are so important for projects like ours, and we’re really grateful that we were able to take advantage of this service.

The matching has generally been very successful. Out of 5,076 names, just over 2,000 were linked from the Hub entry to the VIAF entry, which is a pretty good percentage.

This post provides some perspectives on the nature of the data and the results of the matching work.

Full names and epithets

With a name like ‘Bell, Sir Charles, 1774-1842, knight surgeon’, (you can see his entry in our current Linked Data views at http://data.archiveshub.ac.uk/id/person/ncarules/bellsircharles1774-1842knightsurgeon) there is plenty of information – surname, forename, dates and an epithet to help uniquely identify the individual. However, with this name, a match was not found, despite an entry on VIAF: http://viaf.org/viaf/2619993 (which is why you may not yet see the VIAF link on our Linked Data view). Normally, this type of name would yield a match. The reason it didn’t is that the epithet came through in the data we used for matching.

This highlights an issue with the use of epithets within names. It is encouraged in the NCA Rules, and it does help to uniquely identify an individual, but it introduces an additional element in the string that makes it harder to match the data.

Where our process did not manage to get the family name, forename and dates to match with VIAF, we used the ‘label‘ information that we have in our Linked Data. This label information includes the epithet. For example: Nosek, Václav, 1892-1955, Czechoslovak politician. This doesn’t tend to find a match, because of the epithet. With examples like this we can manually check, and in this case there is a VIAF match (http://viaf.org/viaf/23683886). But manual checking is problematic where you have thousands of names.

In 95% of cases we did manage to omit the epithet. But sometimes the epithet was included because we used the label, as stated, or because the markup on the Archives Hub is not always consistent and sometimes the structured names I referred to above are not present in Hub data because the data has come from other systems. (We may have found a way to remove these stray epithets, but it would have taken a good deal more time and effort to achieve).

Bringing together information on an individual

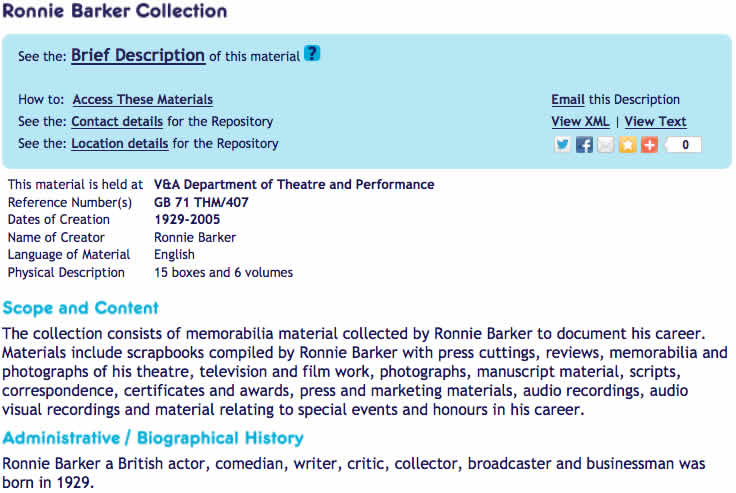

The reference to Sir Charles Bell came from a collection of “Papers of Sir Charles Bell” (http://archiveshub.ac.uk/data/gb96-ms386). In this description his occupation is “surgeon”. In the VIAF description (http://viaf.org/viaf/2619993) he is described as “Scottish painter, draftsman, and engraver”. Ostensibly this doesn’t look like the same person, but looking down the VIAF description, you can see titles such as “The nervous system of the human body” and other works that are clearly written by a scientist. The linking of our description with the VIAF description brings together Sir Charles Bell scientist and Sir Charles Bell painter, a good illustration of how linking provides a better perspective, as the different data sources effectively become joined up.

Pulling sparse sources together

For Francis Campbell Ross Douglas VIAF only has the surname and forename (http://viaf.org/viaf/211588539/), although if you look at the source records you also find “Douglas Of Barloch” to help with identification. This is an example where the Hub record has much more information (http://archiveshub.ac.uk/data/gb097-douglasofbarloch), and therefore creating the link is particularly useful. It shows how archives can help contribute to our knowledge of individuals within the Linked Data space, as they often have little known information, gleaned from the archives themselves.

Hyphenated names

From the Hub description http://archiveshub.ac.uk/data/gb1538-s97 comes the name William Blair-Bell. The name with encoding (slightly simplified) is:

<persname>

<surname>Bell</surname>,

<forename>William Blair-</forename>

(<dates>1871-1936</dates>)

<epithet>British gynaecologist and obstetrician</epithet>

</persname>

This is an example of the application of the NCA Rules, which insist on the last entry element as the main element, so it means the element ‘Bell’ is marked up as the surname. In fact, the matching still works because, with all the elements there, the reconciliation service can still find the right person (http://viaf.org/viaf/14336292/). However, it still concerns me that within the archive sector we have a rule that separates out the surname in this way, as it makes the name non-standard compared to other data sources. It is interesting to note that the name is generally given as Blair-Bell, but the Library of Congress enters the name as Bell, W. Blair (William Blair), 1871-1936 (http://id.loc.gov/authorities/names/no92003069.html), so there is an inconsistency in how different services deal with hyphenated and compound surnames. It could be argued that once we have a match, the different formats matter less, as they are simply alternatives that can be used to identify the individual.

Hub names without structured markup

As stated, in the Hub names are marked up by surname, forename, dates, epithet, titles. However, there are still some entries that are not marked up like this, usually because they were created in proprietary software and exported. An example is Carlyon Bellairs (referenced in http://archiveshub.ac.uk/data/gb097-assoc17). The name is marked up as:

<persname>Bellairs, Carlyon, 1871-1955, RN Commander, politician</persname>

You can see the XML mark up at http://archiveshub.ac.uk/data/gb097-assoc17.xml?hub. We have been working on a script to markup the component parts of these names in the Hub, and we have been able to implement it successfully for several institutions. But it is not easy to do this with non-standard names (i.e. not in the surname, forename, dates, epithet format). We do have some instances of names such as the British Prime Minister, James Callaghan, or the author Rudyard Kipling, that are not yet marked up in this way. These individuals should be easy to match, but without the structure within the index term, it is harder for us to ensure that we can get just the name and dates from an unstructured name to match with VIAF.

It is also impossible to implement structured markup on a name where there is a compound surname entered according to NCA Rules – we simply cannot mark these names up correctly because we have no way of knowing whether part of the forename is actually part of the surname. For example, if we have the name “George, David Lloyd” we can’t write a script that can transform this into “Lloyd George, David” because most of the time a name like this will be two forenames and one surname.

The importance of life dates and the use of ‘Is Like’

If we don’t have life dates, it makes matching with certainty almost impossible. Of course, cataloguers can’t always find life dates for a person, but it is worth stressing that the need for life dates has become even more important in recent years, now we have the potential to process data in so many ways. An example is at http://archiveshub.ac.uk/data/gb532-bel – Joyce Margaret Bellamy, a Senior Research Officer at the University of Hull. As we don’t have a birth date, we did not get a match with her VIAF entry at http://viaf.org/viaf/94773174. If we have this kind of entry, without life dates, we could potentially decide to use a different status from an exact match (which usually uses the owl:sameAs property), and for example, we could use the ‘isLike‘ property from the Umbel vocabulary instead. This would be useful where we believe the two names to be referring to the same person, but this type of matching has to be done manually (although potentially we could run something where a name match without a date match was always an ‘isLike’). In the process of checking the 2,000 matches for our data we did enter a number of matches manually, and the whole process of checking took around 5 hours. Not too bad for 2,000 names, and with some time also given to thinking about the results (and making notes for this post!). But if we were to work on the entire Archives Hub data, we couldn’t undertake to do this kind of manual work unless we just had a few thousand ‘not sure’ names that we might be prepared to work through.

Matches without life dates

We do get matches to VIAF where we don’t have dates. We got a match for ‘Hilda Chamberlain’ with VIAF entry http://viaf.org/viaf/286538995/. This seems to be correct, as she is the daughter of Joseph Chamberlain, so we kept the match. But we had to check it manually. Another example is Hercules Ross – http://viaf.org/viaf/21209582/ – matched to the name in description http://archiveshub.ac.uk/data/gb254-ms17. But in this case we don’t really have enough evidence to identify the individual, even though the surname and forename match. The source of the name on VIAF is “Guild, J. Proceedings before the sheriff depute of Forfarshire … against Hercules Ross and David Scott, Esquires, 1809”, but the title deeds described in the Archives Hub cover the sixteenth to the nineteenth century!

With a name like Gustav Wilhelm Wolff (http://archiveshub.ac.uk/data/gb738-ms174), again we only have the name and not the life dates. The match given is for someone born in 1811 (http://viaf.org/viaf/8221966/), and the papers relate to Victorian Jews in Britain. This makes the match likely, but we can’t be sure without dates, so we could potentially enter an ‘is like’, to imply that they are the same person, but that we cannot be certain.

Floruit!

We had a number of individuals without known life dates where the cataloguer used a ‘floruit’, e.g. Sharman W. fl 1884 (Secretary of National Association for the Repeal of the Blasphemy Laws). This sort of entry, whilst it may be the total of the information the archivist has, is difficult to use to identify someone in order to match them. However, the majority of individuals with this kind of entry are not likely to be on VIAF simply because a floruit normally indicates someone for whom life dates cannot be found. It would be interesting to consider a tool that matches floruit dates to possible life dates (e.g. fl 1900-1910 would match to life dates of 1880-1945) but I’m not sure how much it would add much to the accuracy of a match.

Alternative names

The reconciliation service often works where VIAF provides names that are not ‘the same’ as our name. So, for example, the Hub data may have the name ‘Orton, John Kingsley, 1933-1967’. This was linked to Joe Orton (http://viaf.org/viaf/22163951), and within the VIAF data you can see that Joe Orton is also known as John Kingsley Orton.

Fame does not always give identity

Sometimes very famous people prove problematic, and an example is someone like Queen Victoria, because the name doesn’t include a surname and people tend to enter it in various ways. There were a few examples of this type of thing in our data, although most royal names matched with no problem. It always helps if it is easier to structure a name, but kings, queens, popes, etc. are non-standard.

Some Hub names are quite fulsome, such as “Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David, 1894-1972, Duke of Windsor, formerly Edward VIII, King of Great Britain and Ireland”. This should link to VIAF http://viaf.org/viaf/47553571 (Windsor, Edward, Duke of, 1894-1972), but the match was not given due to the lack of similarity.

Accented characters may cause problems

We didn’t get a match on Jeremy Bentham, despite having the full structured name, but this may be because the VIAF match has an accent: http://viaf.org/viaf/59078842/. We could possibly have stripped out accents in our data, but in this case the accent was in the VIAF data. I only found one example where this was a problem, but clearly many names do contain accented characters.

Matches sometimes surprise…

A particularly nice match came up for “Mary-Teresa Craigie Pearl 1867-1906 novelist, dramatist and journalist as John Oliver Hobbes nee Richards”. A complex string, but the algorithm matched the basic elements that we provided (Cragie Pearl, Mary-Teresa, 1867-1906) to the name ‘John Oliver Hobbes’ on VIAF.

Mismatches

Leonard Wright, a Leiutenant (http://archiveshub.ac.uk/data/gb99-kclmawrightlw) matched to Clara Colby (http://viaf.org/viaf/63445035/), also known as Mrs Leonard Wright Colby. Here is an example of an incorrect match due to the same name, but in VIAF the person is a ‘Mrs’ (due to the old fashioned practice of using the husband’s name). The reason for the match seems to be that the name on the Hub includes a floruit (Leonard Wright, fl 1916) which matches the death date of Mrs Leonard Wright (Leonard Wright, Mrs, d 1916).

On the Hub we have an example of an archive that includes “a letter from Charlotte Bronte to Elizabeth Firth”, and the name is simply given as Elizabeth Firth in the index. The match to VIAF was for Mrs J.F.B Firth (http://viaf.org/viaf/71217693/). In this case the match is wrong, as we can see from the Hub description that Elizabeth Firth is actually “Mrs. James Clarke Franks”, and the dates within the additional information don’t seem to match.

There were very few examples of this type of mismatch, but it shows why well structured data, with life dates, helps to minimize any incorrect matches.

Incorrect Suggestions

In the names that did not find definite matches (i.e outside of the 2,000 matches), there were a few examples of suggested names that did not bear much resemblance to the text provided. One example of this was for “Bell, Vanessa, 1879-1961”. The suggestions for ‘sameAs’ names to link to this individual were Stephen, Julia Prinsep British model, 1846-1895; Woolf, Virginia, 1882-1941; Stephen, Leslie, 1832-1904. In fact, VIAF does have Vanessa Bell (http://viaf.org/viaf/7399364), and the link appears to be that the names are related within VIAF (i.e. VIAF establishes that there is an association between these people). However, these were only suggestions, they were not given as matches.

Conclusions

If there was no match given, but we can see that the name and dates have gone to VIAF, then we would assume there simply is no match and VIAF does not have anyone with our surname, forename and dates. But if we can see an epithet has also been included in the data we have provided, then there may well be a match because the epithet can be problematic for finding a match. Our intention would be to continue to improve our filtering to try to remove all epithets, but if the names are not properly structured this can be difficult.

When actually checking data like this, one thing that really comes to the fore is the risk of a ‘sameAs’ where the individual is not the same, and this is a particular risk where you are dealing with a notorious character – maybe a criminal. A number of war criminals are referred to in the Hub data, and it would be very unwise to link these to the wrong person – this is why it is best to only provide matches where the life dates match, but it is not impossible to have the same name with the same life dates of course.

In conclusion I would say that wherever our names have life dates, and these can be successfully carried over to the matching process, the likelihood of a correct match is 99%, but there is always a risk of a mismatch. Clearly the main problem would lie with two people sharing a name and life dates, and the chances of this happening will increase if we only have birth or death date.

Jisc Linking Lives project at Mimas: Jane Stevenson, Adrian Stevenson, Lee Baylis