Archives Hub feature for August 2019

The North Wales Hospital collection is one of the most popular at Denbighshire Archives. It attracts a variety of different service users including family historians, history students, and academics. The collection is one of the top search terms, and in the top ten performing web pages on the services website.

The North Wales Hospital was originally known as the North Wales Counties Lunatic Asylum, it opened in October 1848 in response to the growing concern of the treatment of the mentally ill in North Wales. As there was no public institution in North Wales, the mentally ill were often inadequately cared for by families, sent to a union workhouse, or sent to an English asylum. In response a group of landed gentry, clergyman, and businessmen met at Denbigh General Infirmary, to call attention to the need for a hospital for the mentally ill. From the outset the group were keen to distance themselves from the typical image of a Victorian Asylum, where patients were locked away or where mechanical restraints were used. They believed that these should be replaced by kind management and moral discipline, provided to patients in their own language, an ethos which stayed with the hospital throughout its life.

After nearly 150 years the hospital closed in 1995, during this time thousands of patients had passed through its doors. The hospital existed at a time of important developments in the treatment of mental health, and was often at the forefront of new experimental treatments, including Electro Convulsive Therapy, Leucotomy procedures, insulin shock therapy, and pharmaceutical advancements designed to treat neurological diseases such as schizophrenia.

The collection is extensive, it includes management records such as minutes and annual reports, building records including some relating to the initial foundation of the hospital, financial records including annual accounts, and staff records including wage books. As well as records reflecting the administrative side of the hospital, the records also reflect the more social and recreational side of hospital life and include records of patient and staff social clubs, sports teams, music, and cinema showings.

There are numerous patient records including case files dating from the opening of the hospital in 1848, admission, and discharge registers, ward reports, registers of deaths, and a large number of patient reception orders. One of the most exciting features of the collection is the series of 30,000 patient files which date from after the formation of the National Health Service in 1948 and run up until the hospitals closure. They are regarded as being uniquely important, in that, they are a complete collection of mental health records that cover the same geographical area of a fairly static population over a long period of time, making them ideal for comparative study.

Whilst records containing sensitive or personal information are closed to the public for 100 years, they will be available for academic research to those belonging to an academic institution. The records are a vital resource for academics and medical professionals, not only do they track the development of institutional psychiatric care and treatment during an exceptional period of innovation in mental health treatments, they also provide intimate details about the lives of the patients and the world they lived in. The records provide a great deal of detail about the patients, with background information provided by the relatives. This social context produces a rare insight into the lives of those not usually given a voice in the historical record.

Previous work carried out on the collection had been met with an enthusiastic response from service users. It was felt that further projects were needed to completely catalogue the collection to make it more accessible, and to build on the keen interest shown. A scoping survey carried out in 2015 confirmed that if the collection was accessible it would be one of the best and richest research resources for medical humanities in North Wales.

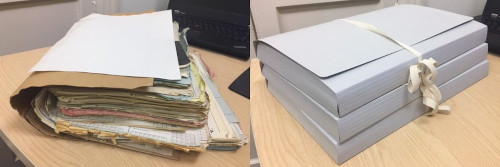

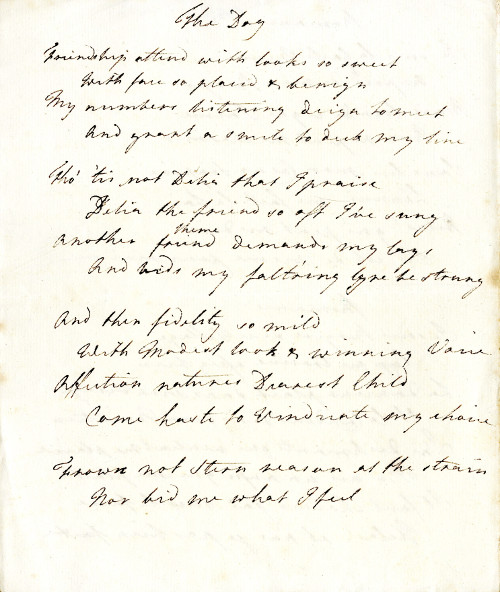

In 2017 Denbighshire Archives received a grant from the Wellcome Research Resources Award to finance the Unlocking the Asylum project. During the two year project the collection has been fully catalogued, repackaged, and assessed for conservation needs. Additionally the series of 30,000 post 1948 patient case files have been fully indexed and repackaged, making them more accessible for academic research than ever before. The patient file index has extracted key details from each file including date of birth, address, admission and discharge dates, dates of death, diagnosis, details of treatments, number of admissions, and details of any supporting documents such as outpatient notes, social work notes, letters, poetry or artwork produced by patients, and reports of court proceedings.

The completed collection catalogue will be available via the Denbighshire Archives website and the Archives Hub at the end of the project. Further details on how to access and use the collection will be available on the Denbighshire Archives website at the end of the project in October 2019.

Lindsey Sutton

Project Archivist (Unlocking the Asylum)

Denbighshire Archives

Related

North Wales Hospital, records of (1848-1995)

Browse all Denbighshire Archives collections on the Archives Hub.

All images copyright Denbighshire Archives and reproduced with the kind permission of the copyright holders.

![Letter from W.S. Kneeshaw to ‘Trevor’ [Mr Trevor of Carter Vincent, Solicitors, Bangor] regarding an invention he intends to patent](https://blog.archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/04/cvabangor_letter.jpg)

![Career guide for married women pursuing paediatrics produced by the BPA due to the increasing number of women graduating in medicine, of which many left the profession due to family commitments. The document proposes that establishing suitable posts and offering retraining schemes and financial inducements could support female paediatricians. 1972 [archive reference: RCPCH/007/141]](https://blog.archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/03/rcpch_guide.jpg)

![Minutes of a meeting of the Executive Committee discussing whether to invite female members of the Canadian Paediatrics Society to a joint meeting in London, 1938 [archive reference: RCPCH/004/002/006]](https://blog.archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/03/rcpch_min1938.jpg)

![Minutes of a meeting of the Executive Committee showing the vote to admit female members into the BPA, 1944 [archive reference: RCPCH/004/003/011]](https://blog.archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/03/rcpch_min1944.jpg)

![Painted design of the RCPCH Coat of Arms featuring June Lloyd, 1997 [archive reference: RCPCH/009/001/014]](https://blog.archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/03/rcpch_coatofarms.jpg)

![Photograph of an early ‘floating institute’ operated by the Missions to Seamen, late 19th century [U DMS].](https://blog.archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/01/seam_institute.jpg)

![Logo of the Flying Angel [U DMS].](https://blog.archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/01/seam_angel.jpg)

![Logo of the Stella Maris [U DAPS/12/4].](https://blog.archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/01/seam_stella.jpg)

![Photograph of the interior of the original Apostleship of the Sea house in Glasgow, c.1920s [U DAPS/7/2].](https://blog.archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/01/seam_house.jpg)

![Photograph of a visit paid to Bishop Rock lighthouse by Missions to Seamen representatives for the Scilly Isles [U DMS].](https://blog.archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/01/seam_visit.jpg)