The 2018 Archives Hub online survey was answered by 83 respondents. The majority were in the UK, but a significant number were in other parts of Europe, the USA or further afield, including Australia, New Zealand and Africa. Nearly 50% were from higher or further education, and most were using it for undergraduate, postgraduate and academic research. Other users were spread across different sectors or retired, and using it for various reasons, including teaching, family history and leisure or archives administration.

We do find that a substantial number of people are kind enough to answer the survey, although they have not used the service yet. On this survey 60% were not regular users, so that is quite a large number, and maybe indicates how many first-time users we get on the service. Of those users, half expected to use it regularly, so it is likely they are students or other people with a sustained research interest. The other 40% use the Hub at varying levels of regularity. Overall, the findings indicate that we cannot assume any pattern of use, and this is corroborated by previous surveys.

Ease of use was generally good, with 43% finding it easy or very easy, but a few people felt it was difficult to use. This is likely to be the verdict of inexperienced users, and it may be that they are not familiar with archives, but it behoves us to keep thinking about users who need more support and help. We aim to make the Hub suitable for all levels of users, but it is true to say that we have a focus on academic use, so we would not want to simplify it to the point where functionality is lost.

I found one comment particularly elucidating: “You do need to understand how physical archives work to negotiate the resource, but in terms of teaching this actually makes it really useful as a way to teach students to use a physical archive.” I think this is very true: archives are catalogued in a certain way, that may not be immediately obvious to someone new to them. The hierarchy gives important context but can make navigation more complicated. The fact that some large collections have a short summary description and other smaller archives have a detailed item-level description adds to the confusion.

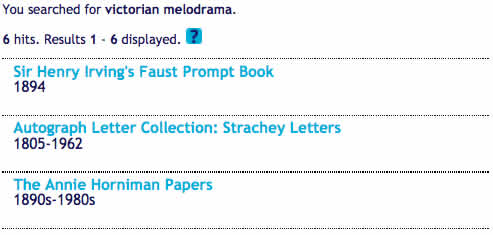

One negative comment that we got maybe illustrates the problem with relevance ranking: “It is terribly unhelpful! It gives irrelevant stuff upfront, and searches for one’s terms separately, not together.” You always feel bad about someone having such a bad experience, but it is impossible to know if you could easily help the individual by just suggesting a slightly different search approach, or whether they are really looking for archival material at all. This particular user was a retired person undertaking family history, and they couldn’t access a specific letter they wanted to find. Relevance ranking is always tricky – it is not always obvious why you get the results that you do, but on the whole we’ve had positive comments about relevance ranking, and it is not easy to see how it could be markedly improved. The Hub automatically uses AND for phrase searches, which is fairly standard practice. If you search for ‘gold silver’ you will probably get the terms close to each other but not as a phrase, but if you search for ‘cotton mills’ you will get the phrase ranked higher than e.g. ‘mill-made cotton’ or ‘cotton spinning mill’. One of the problems is that the phrase may not be in the title, although the title is ranked higher than other fields overall. So, you may see in your hit list ‘Publication proposals’ or ‘Synopses’ and only see ‘cotton mills’ if you go into the description. On the face of it, you may think that the result is not relevant.

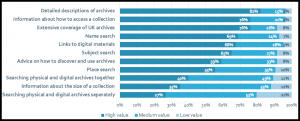

All of our surveys have clearly indicated that a comprehensive service providing detailed descriptions of materials is what people want most of all. It seems to be more important than providing digital content, which may indicate an acknowledgement from many researchers that most archives are not, and will not be, digitised. We also have some evidence from focus groups and talking to our contributors that many researchers really value working with physical materials, and do not necessarily see digital surrogates as a substitute for this. Having said that, providing links to digital materials still ranks very highly in our surveys. In the 2018 survey we asked whether researchers prefer to search physical and digital archives separately or together, in order to try to get more of a sense of how important digital content is. Respondents put a higher value on searching both together, although overall the results were not compelling one way or the other. But it does seem clear that a service providing access to purely digital content is not what researchers want. One respondent cited Europeana as being helpful because it provided the digital content, but it is unclear whether they would therefore prefer a service like Europeana that does not provide access to anything unless it is digital.

Searching by name, subject and place are clearly seen as important functions. Many of our contributors do index their descriptions, but overall indexing is inconsistent, and some repositories don’t do it at all. This means that a name or subject search inevitably filters out some important and relevant material. But in the end, this will happen with all searches. Results depend upon the search strategy used, and with archives, which are so idiosyncratic, there is no way to ensure that a researcher finds everything relating to their subject. We are currently working on introducing name records (using EAC-CPF). But this is an incredibly difficult area of work. The most challenging aspect of providing name records is disambiguation. In the archives world, we have not traditionally had a consistent way of referring to individuals. In many of the descriptions that we have, life dates are not provided, even when available, and the archive community has a standard (NCA Rules) that it not always helpful for an online environment or for automated processing. It actually encourages cataloguers to split up a compound or hyphenated surname in a way that can make it impossible to then match the name. For example, what you would ideally want is an entry such as ‘Sackville-West, Victoria Mary (1892-1962) Writer‘, but according to the NCA Rules, you should enter something like ‘West Victoria Mary Sackville- 1892-1962 poet, novelist and biographer‘. The epithet is always likely to vary, which doesn’t help matters, but entering the name itself in this non-standard way is particularly frustrating in terms of name matching. On the Hub we are encouraging the use of VIAF identifiers, which, if used widely, would massively facilitate name matching. But at the moment use is so small that this is really only a drop in the ocean. In addition, we have to think about whether we enable contributors to create new name records, whether we create them out of archive descriptions, and how we then match the names to names already on the Hub, whether we ingest names from other sources and try to deal with the inevitable variations and inconsistencies. Archivists often refer to their own store of names as ‘authorities’ but in truth there is often nothing authoritative about them; they are done following in-house conventions. These challenges will not prevent us from going forwards with this work, but they are major hurdles, and one thing is clear: we will not end up with a perfect situation. Researchers will look for a name such as ‘Arthur Wellesley’ or ‘Duke of Wellington’ and will probably get several results. Our aim is to reduce the number of results as much as we can, but reducing all variations to a single result is not going to happen for many individuals, and probably for some organisations. Try searching SNAC (http://snaccooperative.org/), a name-based resource, for Wellington, Arthur Wellesley, to get an idea of the variations that you can get in the user interface, even after a substantial amount of work to try to disambiguate and bring names together.

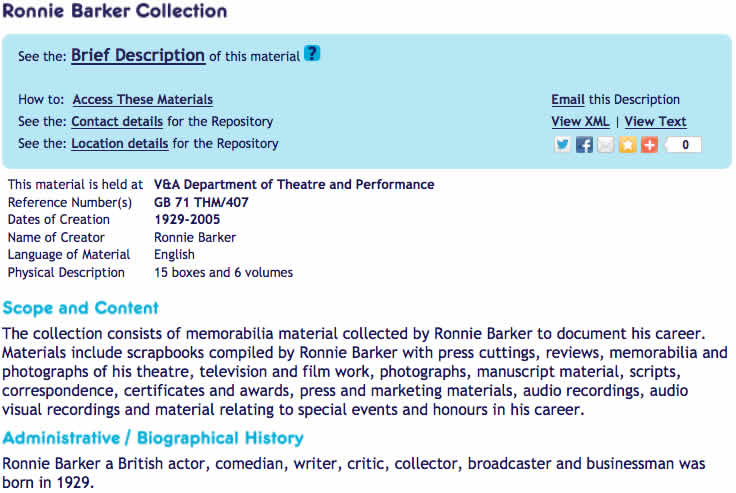

The 2018 survey asked about the importance of providing information on how to access a collection, and 75% saw this as very important. This clearly indicates that we cannot assume that people are familiar with the archival landscape. Some time ago we introduced a link on all top-level entries ‘how to access these materials’. We have just changed that to ‘advice on accessing these materials’, as we felt that the former suggested that the materials are readily accessible (i.e. digital), and we have also introduced the link on all description pages, down to item-level. In the last year, the link has been clicked on 11,592 times, and the average time spent on the resulting information page is 1 minute, so this is clearly very important help for users. People are also indicating that general advice on how to discover and use archives is a high priority (59% saw this as of high value). So, we are keen to do more to help people navigate and understand the Archives Hub and the use of archives. We are just in the process of re-organising our ‘Researching‘ section of the website, to help make it easier to use and more focussed.

There were a number of suggestions for improvements to the Hub. One that stood out was the need to enable researchers to find archives from one repository. At the moment, our repository filter only provides the top 20 repositories, but we plan to extend this. It is partly a case of working out how best to do it, when the list of results could be over 300. We are considering a ‘more’ link to enable users to scroll down the list. Many other comments about improvements related back to being more comprehensive.

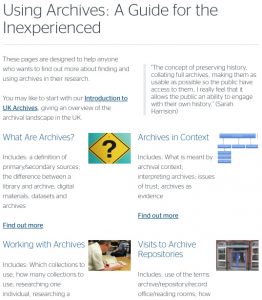

One respondent noted that ‘there was no option for inexperienced users’. It is clear that a number of users do find it hard to understand. However, to a degree this has to reflect the way archives are presented and catalogued, and it is unclear whether some users of the Hub are aware of what sort of materials are being presented to them and what their expectations are. We do have a Guide to Using Archives specifically for beginners, and this has been used 5,795 times in the last year, with consistently high use since it was introduced. It may be that we should give this higher visibility within the description pages.

What we will do immediately as a result of the survey is to link this into our page on accessing materials, which is linked from all descriptions, so that people can find it more easily. We did used to have a ‘what am I looking at?’ kind of link on each page, and we could re-introduce this, maybe putting the link on our ‘Archive Collection’ and ‘Archive Unit’ icons.

It is particularly important to us that the survey indicated people that use the Hub do go on to visit a repository. We would not expect all use to translate into a visit, but the 2018 survey indicated 25% have visited a repository and 48% are likely to in the future. A couple of respondents said that they used it as a teaching tool or a tool to help others, who have then gone on to visit archives. People referred to a whole range of repositories they have or will visit, from local authority through to university and specialist archives.

59% had found materials using the Hub that they felt they would not have found otherwise. This makes the importance of aggregation very clear, and probably reflects our good ranking on Google and other search engines, which brings people into the Archive Hub who otherwise may not have found it, and may not have found the archives otherwise.