Archives Hub feature for December 2020

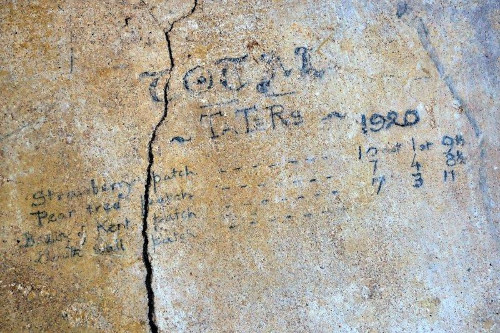

High up on a sheltered, well lit corner of a wall in an outbuilding at Cotesbach Hall can be deciphered a faint scribbling entitled ‘TOTAL TATERS 1920’ [1].

The unmistakeable hand of Rowley Marriott (1899-1992) can be discerned listing the weight of potatoes yielded from each of three areas in the walled garden, to a total imperial equivalent of 1,238 kg, nearly three times what we considered to be an exceptional yield this year, 420kg. Struggling out of the war years, the family having lost two sons on the bloody fields of Flanders and then Father who died of grief in 1918, this harvest would have been no mean feat, and their circumstances many times more challenging than ours. What may seem a trivial detail holds spine tingling resonance for us, a most tangible, personal connection to the people who lived here before us. It was a remarkable harvest a century ago, otherwise the result would never have been written on the wall.

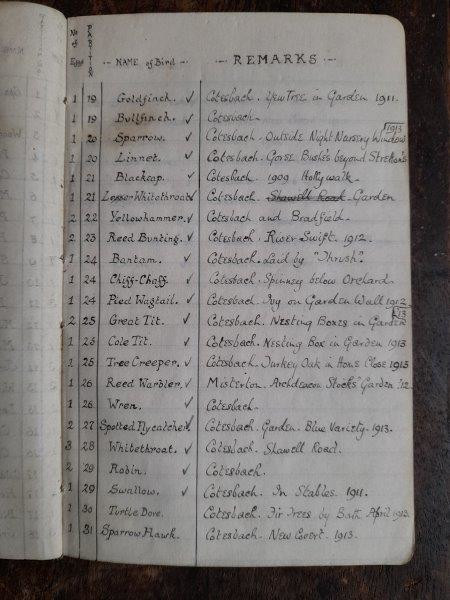

We are very fortunate that the Cotesbach Archive preserves a mine of documents which enable us to piece these stories together connecting people to place, and to wider context. Rowley was one of seven brothers whose boyhood was filled with occupations such as collecting birds eggs [2] and following the hunt, through which they learned to know and love the countryside around, the names and characteristics of each field and spinney.

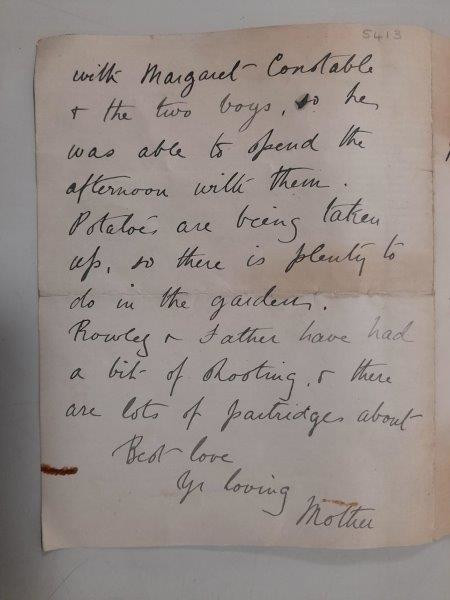

They stepped up to the challenge of vegetable production when the war came along with a spirit of novelty and competition which shows through in Rowley’s letters from his brother Michael, who nicknames him ‘My dear old Parsnip’, signed ‘Your blasted Broccoli’, describing to some extent what and how they were growing. Yet the yield from an initial search on ‘harvest’ in the archive catalogue is sparse: Mother (Mary Emily nee Peach 1862-1934) writing to their elder brother James ca 1914, along with reporting on the tenant farmer’s arable harvest mentions that: ‘Potatoes are being taken up, so there is plenty to do in the garden’ [3, understatement!]. So often, the commonplace is un-remark-able.

Engrossed in cultivation as we have been this year, we are curious for more knowledge of traditional cultivation methods, management, storage, diet. Did they only eat potatoes, and game? Detective work into estate maps, periodic reports, receipts and correspondence will gradually reveal more, but the very absence of everyday detail is an indication of social change. Families of landowners who had previously relied on farm labourers were undergoing hardship themselves and stepped into vegetable production when it was needed most. There were mouths to feed at Cotesbach Hall, 11 residents recorded in the 1911 census, 19 a generation earlier in 1861 out of a village community of 186 (108 in 1911). Harvest time is backbreaking work, dependent on the weather, sadness at the end of summer mingled with celebration of work well done.

It was a way of life, the annual round, which for a scarcely educated farmer would involve attending Sunday church, with its diet of interminable sermons. One such work of Rev. James Powell Marriott delivered for Harvest Thanksgiving on 6th October 1864 warns repeatedly of God’s ultimate harvest of souls and His Almighty Hand which could wreak revenge just as blessing to the crops, implying the villager’s conduct would make a difference, whilst rays of light pouring into the nave would have only reminded him of work to be done, and his disappointment that the Wake or Harvest Festival had been cancelled due to villagers’ overindulgence in previous years. We empathise with that, yet also wonder at the change in values and ideologies, in these days of locked down pews, witnesses as we are of a Faustian reality where humans have induced climate change wreaking havoc with weather patterns, and the need to build and rebuild skills, knowledge and science of the environment which is greater than ever before.

When we agreed to do a slot for the Archives Hub this time last year, the world was a very different place, with our plans to take on four MA students from Leicester University for their summer placements getting under way, the results of which would have provided displays for Heritage Open Days and content for this article. Everything changed with lockdown, yet in all four areas we have made progress, enabling us to be even better placed for next year’s students. Additional HLF funding has brought forward the task of solving the question of migration of our Item level records to the Hub, which involves adopting CALM software, instead of MODES. Back in 2008, the latter seemed the most suitable match for our holistic approach to heritage, our overall aim being to preserve not only the archive but the material culture and books belonging to past generations which retain associations and have already frequently been used as educational resources and display material for the CET. Each object, especially combined with document and imagination, is a doorway into history, into time travel, into discovery.

Our catalogue records need to be as versatile as any of these possibilities, not locked into proprietary arrangements, ensuring it stays relevant and dynamic for new generations. When harvest time comes for our crop of catalogue records it is hoped that the yield will be plentiful, its quality sound, that it will reflect diversity over monoculture, the commonplace and the extraordinary – that there will be much to celebrate and fertile ground for new seed to be sown – starting with new placement proposals for summer 2021.

This year has made us more attuned to the unexpected, more likely to see things with fresh eyes. And so, returning to the most wonderful subject of potatoes, this Smith’s Crisps tin suddenly came into the spotlight, from a dark corner containing bits and pieces roughly where it has sat since the 1930s [4]. My retro-hope is that after all the loss and drudgery, Mother experienced the pleasure of a ‘dainty and appetising’ potato crisp before her day of reckoning.

Sophy Newton

Heritage Manager (Hon)

Cotesbach Educational Trust

Related

Records of the Marriott Family of Cotesbach, 1661-1946 on the Archives Hub

Cotesbach on Instagram

@cotesbach_educational_trust

@cotesbach_organic

@cotesbachestate

All images copyright Cotesbach Educational Trust. Reproduced with the kind permission of the copyright holders.