Archives Hub feature for July 2023

Duden’s Lexicon adopts the classic British proclivity for the understatement in its definition of Vergangenheitsbewältigung: “public debate within a country on a problematic period of its recent history…”. The fact is, however, that the term is commonly understood to mean Germany’s coming to terms (or not) with the Holocaust both collectively and on an individual basis.

There has been a proliferation of literature on the subject in the last couple of decades so much so that the Wiener Holocaust Library (WHL) has a whole section dedicated to it. Publications include scholarly analyses of guilt and shame in entire communities at one extreme to personal memoirs detailing how individual families wrestled with the role of their forbears. No doubt the lapse of time since the events themselves has facilitated this dialogue – in many cases initiated by 2nd , 3rd and even 4th generation Germans.

Whilst WHL holds a number of primary source materials from the point of view of the perpetrator, these take the form of published memoirs and diaries of prominent Nazis and reprinted testimony from defendants and witnesses in war crimes trials. The overwhelming majority of the library’s original manuscript diaries letters and personal documents stem from the families of the victims of Nazi persecution.

A rare exception is one letter unearthed amongst the Wiener Library holdings almost 20 years ago. The very recent discovery of it via a description on the portal, Archives Hub https://archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/data/gb1556-wl703, has immersed the family of the author in an intense period of soul-searching .

What was for years considered an orphan work bereft of information regarding provenance and custodial history has now been identified as the letter of someone’s father. The full import of the contents sent a shockwave through the family.

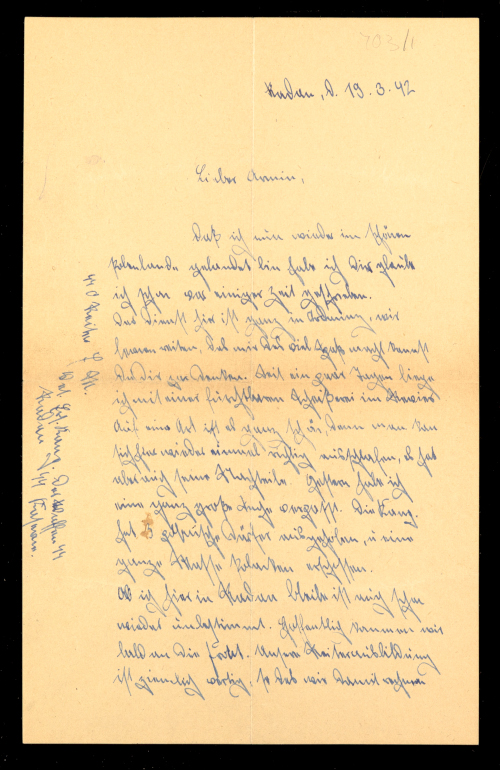

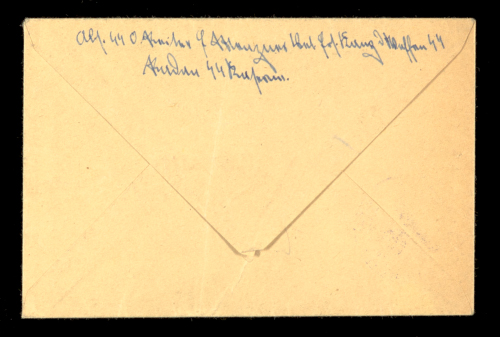

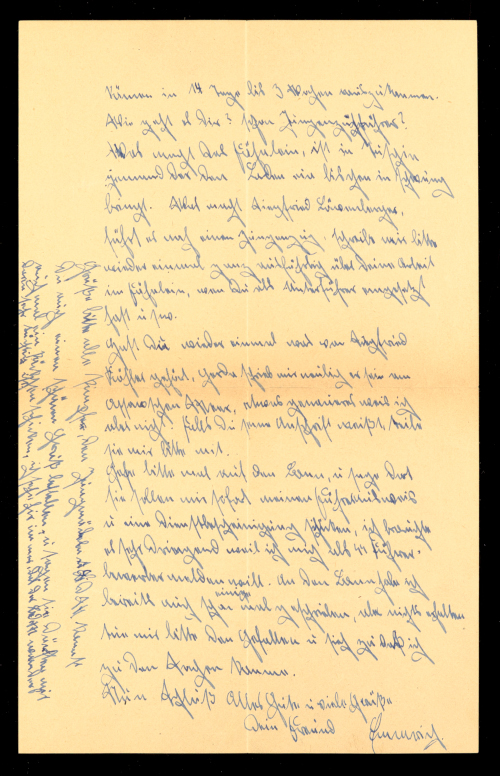

Notwithstanding the absence of any contextual information the letter and its envelope always seemed genuine. The extraneous elements bear all the hallmarks of authenticity: the abbreviated regimental markings, the Sütterlin Schrift, even the paper seem to fit. Then when you read the content one is left with little doubt that this is the real thing.

The letter is written by a teenage rank and file member of an SS cavalry regiment temporarily holed up in a medical facility in an unidentified part of Poland in March 1942 to one of his pals in a town called Rückwerda near Litzmannstadt (Lodz). It is essentially a chatty communication, keeping a friend up to date with what’s going on in his life and referring to mutual acquaintances etc. So far, so unremarkable. Then at the end of the first paragraph the author nonchalantly mentions that whilst he was able to get some rest in the hospital, the experience has had its disadvantages, namely:

“Yesterday I missed out on a really great thing. The company raided 3 villages and shot a whole bunch of Polacks”

He immediately resumes recounting the banalities of his daily existence without a pause for breath.

The statement is shocking on a number of levels not least the casual way it is woven into this chatty catch-up communication: the perjorative term he uses for Poles and the collective noun not appropriate for humans (original German: eine ganze Masse von Polacken) indicates a derisive, superior attitude; the raiding of villages suggests non-combatants; the fact that he regretted missing out on the event; the absence of any empathy for the victims; the naivity of the admission; and the sense that his attitude appears not to be untypical all contribute to the portrayal of a mindset at variance with what one would expect in a civilised society.

When I catalogued this letter all those years ago, with the help of a colleague we transcribed and translated it. We also attempted to locate the place (Radau?) with the assistance of an academic who has subsequently published a study of SS Cavalry Brigade:

https://wiener.soutron.net/Portal/Default/en-GB/RecordView/Index/89808

The item has been available to readers ever since.

Then out of the blue a couple of months ago I was contacted by the husband of a cousin of the author’s son, who had spotted the catalogue description online. Since the name is relatively rare, Emmerich Menzer [i](subsequently corrected to Emmrich), he felt sure that it was his wife’s relative. I sent him a copy of the original and the transcript – they struggled reading the Sütterlin script.

Once they had fully digested the contents my correspondent reported back:

“The transcription you sent us yesterday has shocked all of us and […….] [ii] in particular he finds it hard to believe that his caring, loving father was able to utter his regret for having missed ‘a really big thing’ which involved shooting tens, if not hundreds of innocent civilians…”.

On reflection, he observed how it wasn’t uncommon for perpetrators to lead parallel lives: behave like normal, loving family members and at the same time perpetrate war crimes and crimes against humanity- one only has to look at the role of concentration camp guards and commandants.

I asked him to supply biographical details and he duly obliged:

“I assume Emmrich grew up in a very conservative to nationalistic household and was certainly influenced very much by his father (the one who bought the weekly NPD newspaper every Saturday after the war). Already in 1934 as a Hitlerjugend member Emmrich was promoted to “Jungzugführer” at the tender age of 9, so joining the Waffen-SS seems to have been the logical path. As you know he was a founding member of the local NPD chapter after the war so he probably still agreed with the Nazi ideology although he didn‘t mention anything to his children. Perhaps he was ashamed of his actions during the war or the felt his attitude would not be welcome in post-war Germany and just shut up. But this is just speculation.”

He had also made the observation that whilst only 17 when he wrote the letter, he was already Oberreiter ie a rank above Reiter which suggests that he had been with the unit for some time. He makes the further point that the riding lessons he is supposed to have undertaken- which he also mentions in the letter – must have been specific to the requirements of the cavalry as he was already an accomplished horseman.

This exceptionally rare survival of an admission to these heinous crimes committed by a Waffen SS Cavalry unit is evidence above all of the power of Nazi ideology on someone who had effectively been groomed from a young age to be one of Hitler’s willing executioners.

Howard Falksohn, Senior Archivist

The Wiener Holocaust Library

[i] Note this article was written with the consent of the Emmerich Menzer’s relative. All other names have been omitted.

[ii] Name withheld.

Related

Menzner, Emmerich, SS Oberreiter: Letter from Poland (1942)

Browse all The Wiener Holocaust Library descriptions available to date on the Archives Hub.

All images copyright The Wiener Holocaust Library. Reproduced with the kind permission of the copyright holders.