Archives Hub feature for July 2022

In April 2021, work began to catalogue key collections of the Cavendish family papers in the Devonshire Collection Archives at Chatsworth House, funded by an Archives Revealed Cataloguing Grant.

At the completion of this project, the collections listed below will be searchable using the item-level catalogues on Archives Hub:

- The Hardwick manuscripts, 14th-19th century

- The Papers of and relating to Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679);

- Cavendish Family and Associates: 1st Correspondence Series, 1490-1839

- Correspondence of William Cavendish, 4th Duke of Devonshire (1720-1764)

- Correspondence of William Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire (1833-1908)

Rather than regurgitating the Scope and Content of the catalogues in this blog (which you can read if you click on the links above), I’d like to highlight ten thoughts/statements prompted by items I came across when cataloguing.

It must be acknowledged that this material was largely created and collected by the upper echelons of privileged British aristocratic society, and so the view provided by the material relates to people who were, on the whole, white, wealthy and powerful. Glimmers of other peoples’ stories can be ascertained sometimes, but usually as a by-product of the record creation and retention process rather than directly from those individuals.

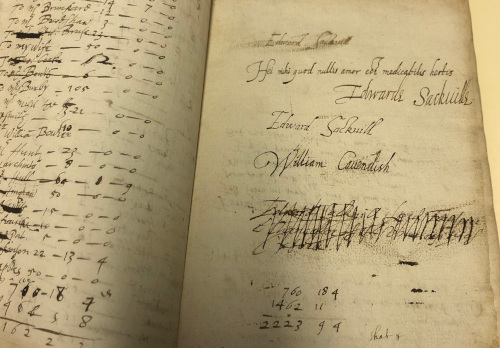

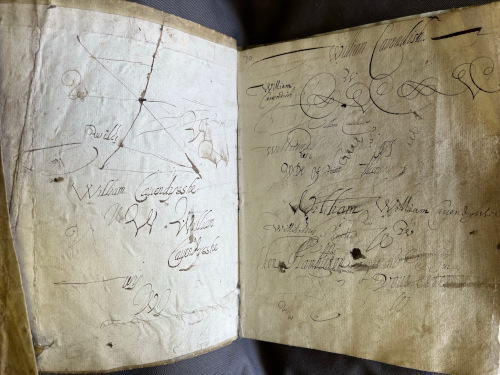

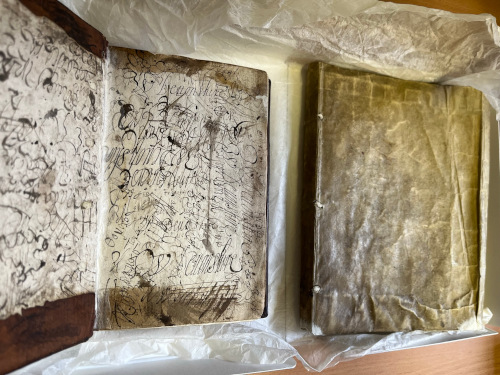

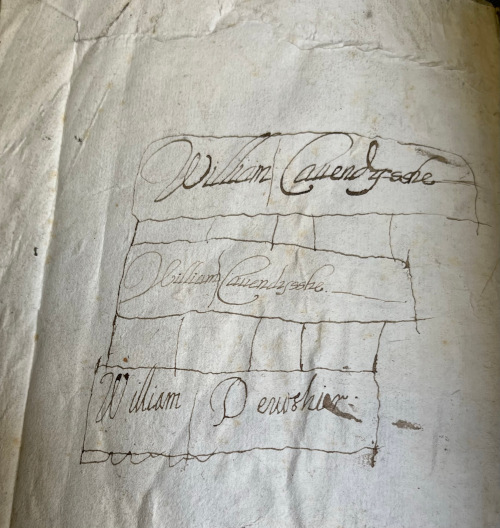

1. School-aged children will always doodle in their exercise books

A number of 17th century exercise books belonging to the 2nd and 3rd Earls of Devonshire are part of the Hardwick Manuscripts (HMS) and Hobbes Papers (HS). Many of them are covered in griffonage on the flyleaves, just as one might expect of a schoolbook today.

They include the 3rd Earl practising his new name “William Devonshire” When, aged 9 ½ he lost his father, the title of Earl of Devonshire passed to him, therefore entitling him to sign himself with the surname Devonshire rather than Cavendish.

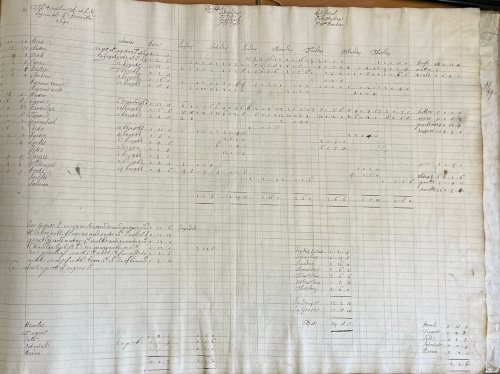

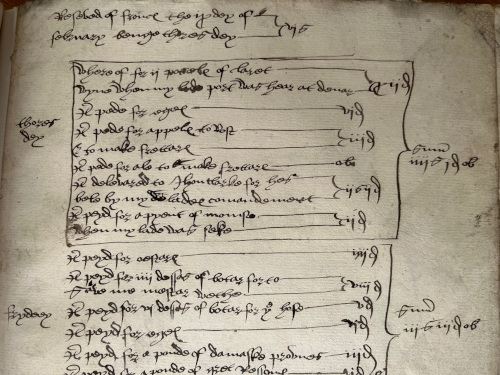

2. Financial account books are a window into daily life

The Hardwick Manuscripts include some astonishingly well-preserved 16th– and 17th-century financial account books from across the Devonshire estates. Some of the most fascinating for the study of daily life in an English aristocratic household are those that record the grocery shop!

Here is an example of Bess of Hardwick’s household spending recorded by her steward for one Thursday in February 1552:

two poteles of claret wine for dinner; eggs; apples to roast; items to make fritters; ale to make fritters; an item delivered to a person for his “bele”; a pint of “momse” for when her ladyship was sick – totalling 4 shillings, 1 ½ pence.

As well as listing provisions (food bought from tenant farmers on the estates) and achats (food bought from town), the kitchen accounts for the 3rd Earl’s household for the years 1640-1678 note the guests dining on particular days. Names include: Lord [Henry] Clifford; Lady Windsor; Lady Salisbury [mother to Elizabeth, Countess of Devonshire]; Lord Cranborne [brother of Elizabeth] and Sir Ed Caple [possibly Cappell, a known Royalist family].

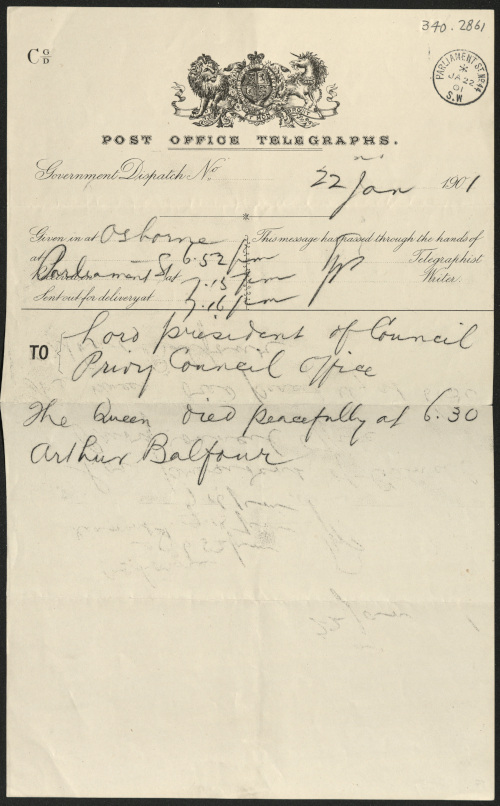

3. Death was still upsetting even though it was common

Losing a family member or friend during one’s own lifetime may have been more common in the 17th and 18th century, but letters in these collections suggest it was not any less of an emotional event because of its regularity.

The letters of Rachel, Lady Russell (c. 1636-1723), show how the execution of her husband – in 1683 for his involvement in the treasonous Rye House Plot – affected her for a long time afterwards. She put on a public show of composure to most of her correspondents. However, her innermost sorrow and grief she shared with her chaplain, Dr Fitzwilliam.

Even three years after her husband’s death she writes:

“…desiring to know the world no more, [I] am utterly unfitted for the management of anything in it, but must, as I can, engage in such necessary offices to my children, as I cannot be dispensed from, nor desire to be, since ‘tis an eternal obligation upon me, to the memory of a husband, to whom, and his, I have dedicated the few and sad remainder of my days, in this vale of misery and trouble.”

4. Women held power

Despite Lady Russell’s deep sorrow that lasted most of the rest of her life, she continued to engage a network of acquaintances through her letter writing. Reading her letters provides a picture of a woman who used the position of a wealthy widow to her advantage in the advance of her estates and her daughters’ positions in society. There are many letters between Lady Russell and her lawyer, John Hoskins (CS1/34); and her cousin Henri de Massaue, 2nd Marquis du Ruvigny (CS1/97). They present an example of how aristocratic women engaged with the management of their estates as much as – and sometimes more than – male landowners, when their widowhood provided them with the opportunity to take control.

Another example of this is Dorothy Boyle (nee Savile), Countess of Burlington (CS1/164), who like Lady Russell, was responsible for the preservation of large groups of inherited family letters, which make up the Cavendish Family and Associates: 1st Correspondence Series, 1490-1839 (CS1) collection at Chatsworth. The archive is a place of power, and the stewardship of family papers ensured these two women could assert theirs.

5. Archival sources and scholarship don’t always align

In most scholarship, the portrayal of Dorothy, Lady Burlington’s influence and legacy is almost non-existent. Eclipsed by the reputation of her architect husband, Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington, Lady Burlington has been a footnote or a minor character in repeated anecdotes. Her letters illuminate a more significant role as a facilitator of the Burlington circle and in 18th-century artistic society. You can read more here.

6. Mental health illness isn’t a modern issue

Many references are made to ‘low mood’, ‘upset humours’, ‘delirium’, ‘nerves’, ‘nervous cases’, ‘hysterics’ in the 18th century letters. Whilst some of the language used is different to how we would describe illnesses such as depression and anxiety today, the references do show that mental health was a case for comment just as much as peoples’ physical health.

Elizabeth Biddulph (nee Bedingfeld) wrote to Lady Charlotte, Marchioness of Hartington in 1754 (CS1/378/1) of her prolonged “illness of the nerves” that began after the birth of her last child. Could she be describing what we would nowadays identify as post-partum depression?

7. Fresh air and exercise were known cures for illness

As with the above letter where we see that fresh air and exercise aided Elizabeth Biddulph’s recovery, the 4th Duke of Devonshire’s brother, Lord Frederick Cavendish, in December 1761, advised his brother to partake of the same. The 4th Duke, having suffered from a bout of poor mental and physical health, was given the following warning by his brother:

“if you set in that room in London and fret yourself about our damned politics, you’ll kill yourself. Go down to Chatsworth look at your works, and keep yourself out in the air the whole day, I don’t joke… if you was to sleep once or twice a week on the top of Lindop [woods near Chatsworth] I believe it would be better than all the physic that doctors can give”. (CS4/1565)

8. It’s possible to draw out historically overlooked people in fleeting remarks

A passing reference to three black children arriving on a French cargo ship into Waterford 1756 in one of the letters of Lord Frederick Cavendish led me to research who they were and what might have happened to them. You can read the full story here.

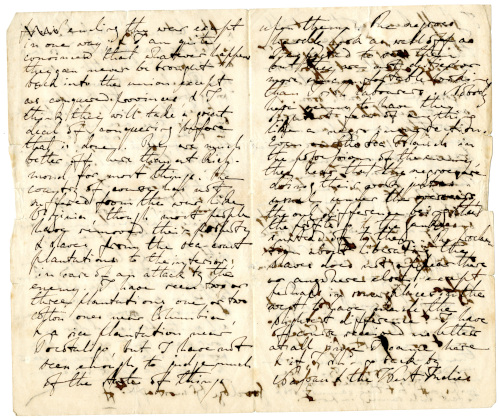

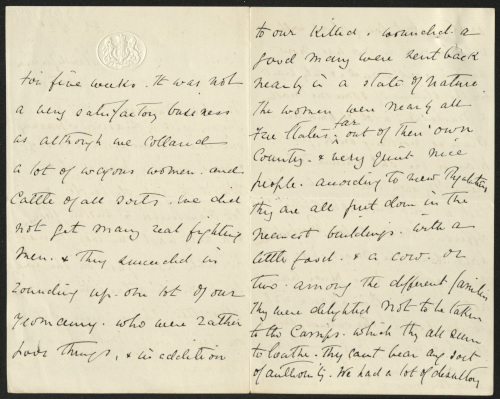

9. Lord Hartington visited Confederate lines and it changed his opinion of the South

Spencer Compton Cavendish, Lord Hartington (1833-1908), visited North America in 1862/3, during the American Civil War. He wrote to his father, the 7th Duke of Devonshire, that seeing the Confederates and their earnestness at Richmond had caused him to begin to support their view. He described himself as becoming more “Southern” as the trip progressed and believed the Southerners to have a lot of “dignity”. This was around the time of Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation (1 January 1863) that “all persons held as slaves” within the rebellious states, “are, and henceforward shall be free”, which would have the biggest effect on some of the Southern states.

Hartington admitted he had not seen enough plantations to be a judge of “the state of things”. However, he wrote that “the “Negroes” hardly look as well off as I expected to see them but they are not [different?] or more uncomfortable looking than Irish labourers” (CS8/184) – a damning indictment of the state of conditions for 19th century Irish labourers!

On the 21 January 1863 he wrote to his father from Charleston, South Carolina, that the Emancipation Proclamation hadn’t seemed to make “the slightest difference” and “even in the Sea Islands [Georgia] in the possession of the enemy, they hear that the “negroes” are doing their work just as usual under the overseers”.

These changed views were clearly private ones as, in another letter to his father, he acknowledges his constituents would not approve of his Southern persuasions (CS8/186).

10. British concentration camps existed before Nazi ones

A reference in a letter from Sir Lawrence Oliphant to Louisa Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire, February 1900 (CS8/2824), mentions his arrival in South Africa and the capture of Boer weapons, women and cattle. He mentions a group of “Freestater” women [from the Orange Free State] who were “delighted not to be taken to the camps”. A reminder that the British used concentration camps for Boer women and children in the South African Boer War – a generation before the Nazis.

I hope that these ten points have shown what wide-ranging material is featured in the Cavendish family papers catalogued in this project and the benefit of having the full catalogues available online on Archives Hub!

Frankie Drummond Charig

Project Archivist, Chatsworth

Related

Browse all Devonshire Collection Archives, Chatsworth descriptions on the Archives Hub

Previous feature on The Devonshire Collection Archives, Chatsworth (2019)

* Portrait of Rachel Wriothesley, Lady Russell. Engraved by John Cochran after a portrait by Samuel Cooper. Image in the public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

All other images copyright The Devonshire Collection Archives, Chatsworth. Reproduced with the kind permission of the copyright holders.

1 Comment

Comments are closed.