Archives Hub feature for March 2015

The Wellcome Trust is currently funding a project to catalogue and conserve the records of the Royal Scottish National Hospital (RSNH), Larbert. The historical importance of the collection was recognized by its inclusion in the UNESCO UK Memory of the World Register in 2013.

The foundation of the Institution

The background to the Institution’s revolutionary approach lies in its reaction to the prevailing social attitudes of the time. Prior to the Mental Deficiency Act 1913, there was no distinction made between mental illness and mental impairment. If children with learning disabilities could not be looked after by their families the alternatives were the poorhouse or an adult lunatic asylum.

The concern generated by this situation resulted in the foundation of the Society for the Education of Imbecile Youth in Scotland in 1859. The Society supported a small school in Edinburgh but it became clear that in order fully to realise their vision, they needed their own premises. In Edinburgh, according to the first annual report, any negotiations with landlords ended as soon as the purpose of the proposed Institution was known. They had to look outside the city and land in Larbert, with its excellent rail links, was chosen.

Initially the children were admitted on a fee-paying basis. For those whose families could not afford the fee the Institution paid, following the election of suitable applicants by donors to the Society.

Applications for admission

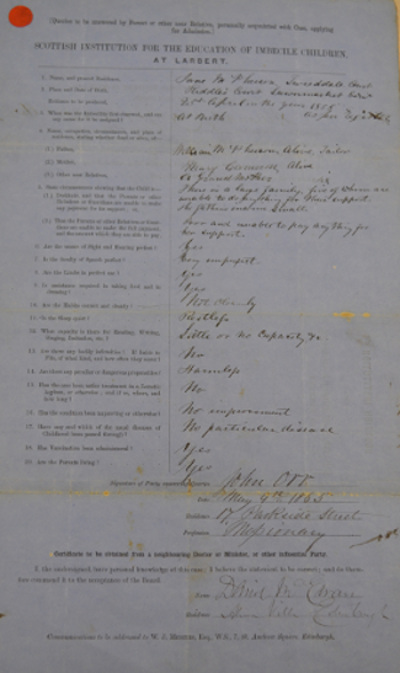

This election process created one of the most important parts of the collection: the applications. Around 3000 of these have survived dating from 1865 to the 1940s. Most early applications include a form titled ‘Queries to be answered by Parent or other near Relative personally acquainted with Case, applying for admission’. This form asks for information on the family’s circumstances as well as the child’s health, behaviour and educational abilities.

Usually accompanying the form is a medical certificate signed by a local doctor which classifies the child’s abilities as Class 1 – very hopeful; Class 2 – hopeful; Class 3 – less so; and Class 4 – subject to severe and frequent fits. To ensure the success of its chosen applicants, the Institution makes it clear on this second form that ‘cases of insanity, of confirmed epilepsy, of the deaf and dumb, and of the blind are ineligible for admission except upon payment’.

Electioneering was expected and applicants were often direct in their approach. One letter asks for a list of subscribers so they could be asked for their votes. Another indicates how large a donation could be expected from the locality on the election of the desired candidate. Lobbying on behalf of applicants became such as nuisance that as early as 1864 the Directors voted to ban the use of cards in canvassing as ‘expensive to the parents and an annoyance to the subscribers’.

Many of the applications include correspondence. One early application was for a boy from Saltcoats called Charles McLarty. According to his form he was admitted in 1881 at the age of 15. But the application includes four letters written between 1927 and 1933 presumably from a relative, asking about his health and sending him sweets. At the age of 67 Charlie was still at the Institution.

This issue of adults in what was ostensibly a children’s Institution exercised the Commissioners in Lunacy during their twice-yearly inspections. One wrote in 1876 ‘[it] is no longer as to the detention of one or two exceptional cases, but it applies to a third or more of the inmates’. They requested that the situation be regularised with orders of the sheriff and a paid licence. But given the lack of any suitable Institution to discharge them to, many were kept on as servants in the Institution or were simply paid boarders. It was only with the opening of the Industrial Colony for Adults in 1935 that the Larbert Institution could officially be said to provide all-life care.

Life in the Institution

There is ample evidence that the children were treated with kindness. Even in a source as potentially dry as the cash book there are entries devoted to payments for travelling musicians, toys for children and bonnets for boys.

Three and a half hours of schooling were given each day in the early years of the Institution but even training was seen as pleasurable: ‘kindly instructors and happy children’ as one inspector described the workshops in 1927. And there were plenty of leisure activities provided. Picnics were popular as were the introduction of ‘talkies’ in 1936. These were described in the minutes: ‘no innovation has given greater pleasure than this either in anticipation, realisation or retrospect’.

It is easier to understand the medical superintendent’s bewilderment in 1920 when faced with three runaways from the Institution in the one month. One boy had only been in the Institution a week ‘and was home-sick for a garret in a horrible slum in Glasgow…[with] no furniture’.

The RSNH on the Archives Hub

The collection description is already available on the Archives Hub. The rest of the collection will be added when the project ends in July this year. It will also be available on the University of Stirling’s own catalogue: http://www.calmview.eu/stirling/CalmView/Default.aspx.

Other highlights of the collection include admissions registers (1863-19880, minute books (1863-1969), annual reports (1862-1948) and correspondence (1881-1965).

University of Stirling collections on the Archives Hub

The university’s collections are as diverse as would be expected but are particularly strong in the areas of film-making, politics, literature and sport. Highlights of the collections on the Archives Hub include Lindsay Anderson (1923-1994) film director; James Hogg (1770-1835) poet and novelist; and the extensive collection of political papers, pamphlets and newspapers of William Tait (1889-1941) socialist labour politician.

Alison Scott, Project Archivist

University of Stirling

All images copyright the University of Stirling, and reproduced with the kind permission of the copyright holder.