For many of us, the importance of measuring use and impact are coming more to the fore. Funders are often keen for indications of the ‘value’ of archives and typically look for charts and graphs that can provide some kind of summary of users’ interaction with archives. For the Hub, in the most direct sense this is about use of the descriptions of archives, although, of course, we are just as interested in whether researchers go on to consult archives directly.

The pattern of use of archives and the implications of this are complex. The long tail has become a phrase that is banded around quite a bit, and to my mind it is one of those concepts that is quite useful. It was popularised by Chris Anderson, more in relation to the commercial world, relating to selling a smaller number of items in large quantities and a large number of items in relatively small quantities, and you can read more about it in Wikipedia: Long Tail.

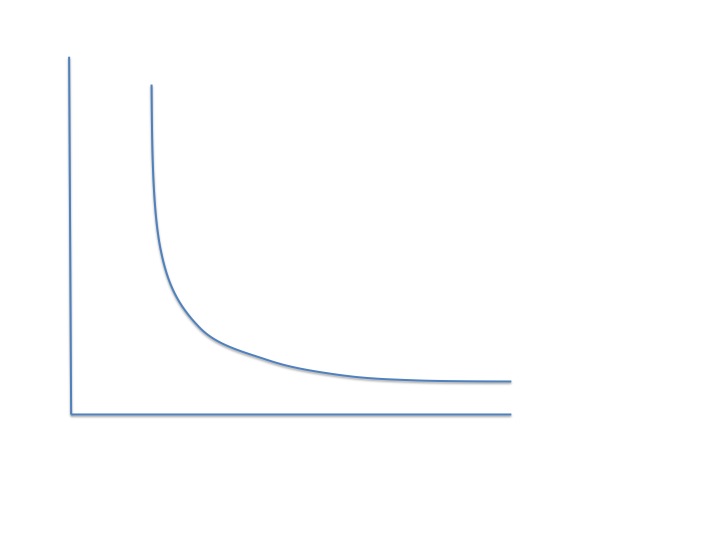

If we think about books, we might assume that a smaller number of popular titles are widely used and use gradually declines until you reach a long tail of low use. We might think that the pattern, very broadly speaking, is a bit like this:

I attended a talk at the UKSG Conference recently, where Terry Bucknell from the University of Liverpool was talking about the purchase of e-books for the University. He had some very whizzy and really quite absorbing statistics that analysed the use of packages of e-books. It seems that it is hard to predict use and that whilst a new package of e-books is the most widely used for that particular year, the older packages are still significantly used, and indeed, some books that are barely used one year may be get significant use in subsequent years. The patterns of use suggested that patron-driven acquisition, or selection of titles after one year of use, were not as good value as e-book packages, although you cannot accurately measure the return on investment after only one year.

Archives are kind of like this only a whole lot more tricky to deal with.

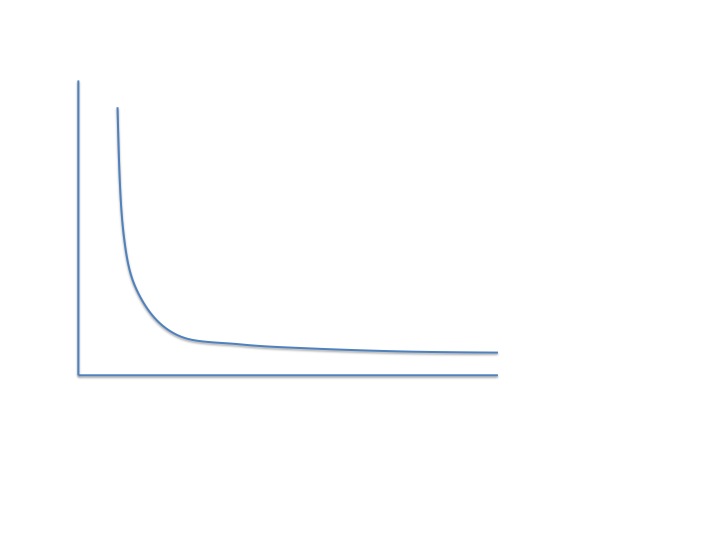

For archives, my feeling is that the graph is more like this:

No prizes for guessing which are the vastly more used collections*. We have highly used collections for popular research activities, archives of high-profile people and archives around significant events, and it is often these that are digitised in order to protect the originals. But it is true to say that a large proportion of archives are in the ‘long tail’ of use.

I think this can be a problem for us. Use statistics can dominate perceptions of value and influence funding, often very profoundly. Yet I think that this is completely the wrong way to look at it. Direct use does not correlate to value, not within archives.

I think there are a number of factors at work here:

- The use of archives is intimately bound up with how they are catalogued. If you have a collection of letters, and just describe it thus, maybe with the main author (or archival ‘creator’), and covering dates, then researchers will not know that there are letters by a number of very interesting people, about a whole range of subjects of great interest for all sorts of topics. Often, archivists don’t have the time to create rich metadata (I remember the frustrations of this lack of time). Having worked in the British Architectural Library, I remember that we had great stuff for social history, history of empire, in particular the Raj in India, urban planning, environment, even the history of kitchen design or local food and diet habits. We also had a wonderful collection of photographs, and I recall the Photographs Curator showing me some really early and beautiful photographs of Central Park in New York. Its these kind of surprises that are the stuff of archives, but we don’t often have time to bring these out in the cataoguing process.

- The use of a particular archive collection may be low, and yet the value gained from the insights may be very substantial. Knowledge gained as a result of research in the archives may feed into one author’s book or article, and from there it may disseminate widely. So, one use of one archive may have high value over time. If you fed this kind of benefit in as indirect use, the pattern would look very different.

- The ‘value’ of archives may change over time. Going back to my experience at the British Architectural Library, I remember being told how the drawings of Sir Edwin Lutyens were not considered particularly valuable back in the 1950s – he wasn’t very fashionable after his death. Yet now he is recognised as a truly great architect, and his archives and drawings are highly prized.

- The use of archives may change over time. Just because an archive has not been used for some time – maybe only a couple of researchers have accessed it in a number of years – it doesn’t mean that it won’t become much more heavily used. I think that research, just like many things, is subject to fashions to some extent, and how we choose to look back at our past changes over time. This is one of the challenges for archivists in terms of acquisitions. What is required is a long-term perspective but organisations all too often operate within short-term perspectives.

- Some archives may never be highly used, maybe due to various difficulties interpreting them. I suppose Latin manuscripts come to mind, but also other manuscripts that are very hard to read and those pesky letters that are cross-written. Also, some things are specialised and require professional or some kind of expert knowledge in order to understand them. This does not make them less valuable. It’s easy to think of examples of great and vital works of our history that are not easy for most people to read or interpret, but that are hugely important.

- Some archives are very fragile, and therefore use has to be limited. Digitising may be one option, but this is costly, and there are a lot of fragile archives out there.

I’m sure I could think of some more – any thoughts on this are very welcome!

So, I think that it’s important for archivists to demonstrate that whilst there may be a long tail to archives, the value of many of those archives that are not highly used can be very substantial. I realise that this is not an easy task, but we do have one invention in our favour: The Web. Not to mention the standards that we have built up over time to help us to describe our content. The long tail graph does demonstrate to us that the ‘long tail of use’ can be just as much, or more, than the ‘high column of use’. The use of the Web is vital in making this into a reality, because researchers all over the world can discover archives that were previously extremely hard to surface. That does still leave the problems of not being able to catalogue in depth in order to help surface content…the experiments with crowd-sourcing and user generated content may prove to be one answer. I’d like to see a study of this – have the experiments with asking researchers to help us catalogue our content proved successful if we take a broad overview? I’ve seen some feedback on individual projects, such as OldWeather:

“Old Weather (http://www.oldweather.org) is now more than 50% complete, with more than 400,000 pages transcribed and 80 ships’ logs finished. This is all thanks to the incredible effort that you have all put in. The science and history teams are constantly amazed at the work you’re all doing.” (a recent email sent out to the contributors, or ‘ship captains’).

If anyone has any thoughts or stories about demonstrating value, we’d love to hear your views.

* family history sources

According to the recent Indexing and Authority Records Survey (which I have been blogging about recently), archivists have a number of reasons why they think it is important to undertake place indexing:

According to the recent Indexing and Authority Records Survey (which I have been blogging about recently), archivists have a number of reasons why they think it is important to undertake place indexing: