Update May 2015: Please Note we need to make some changes to the Excel template and we are not currently working with Excel data. We hope to be able to offer this service in the future.

As part of Project Headway we wanted to create an Excel template which archives could use to catalogue and create EAD. We know that some archives – especially smaller and under-resourced archives – are using spreadsheets or word processing software to catalogue, and often lack the time or resources to switch to using an archival management system. While users can catalogue directly on to the EAD Editor, this isn’t a perfect solution – it won’t work in some older browsers, or offline.

While we would have liked to offer a script that allowed users to convert their own Excel catalogues to EAD, it soon became apparent that this wasn’t an option. We would have needed to produce a script for each institution, and relied on the institution using Excel in a very consistent, systematic way – and a way that was ISAD(G) compliant, and could easily be mapped to EAD. So we decided to start off with a simple template, which we can adapt to individual user needs if required.

I’d never worked with XML in Excel before, and a lot of the process was simply trial-and-error, googling error messages, and sending forlorn messages to my programmer husband asking ‘what on earth is denormalised data and how do I stop it?’. I found the office.microsoft.com and msdn.microsoft.com sites useful for figuring out the basics of getting XML in and out of Excel – though I often turned to support elsewhere, too (eg Microsoft support will only tell you that denormalised data is not supported – not what it is or how to fix it).

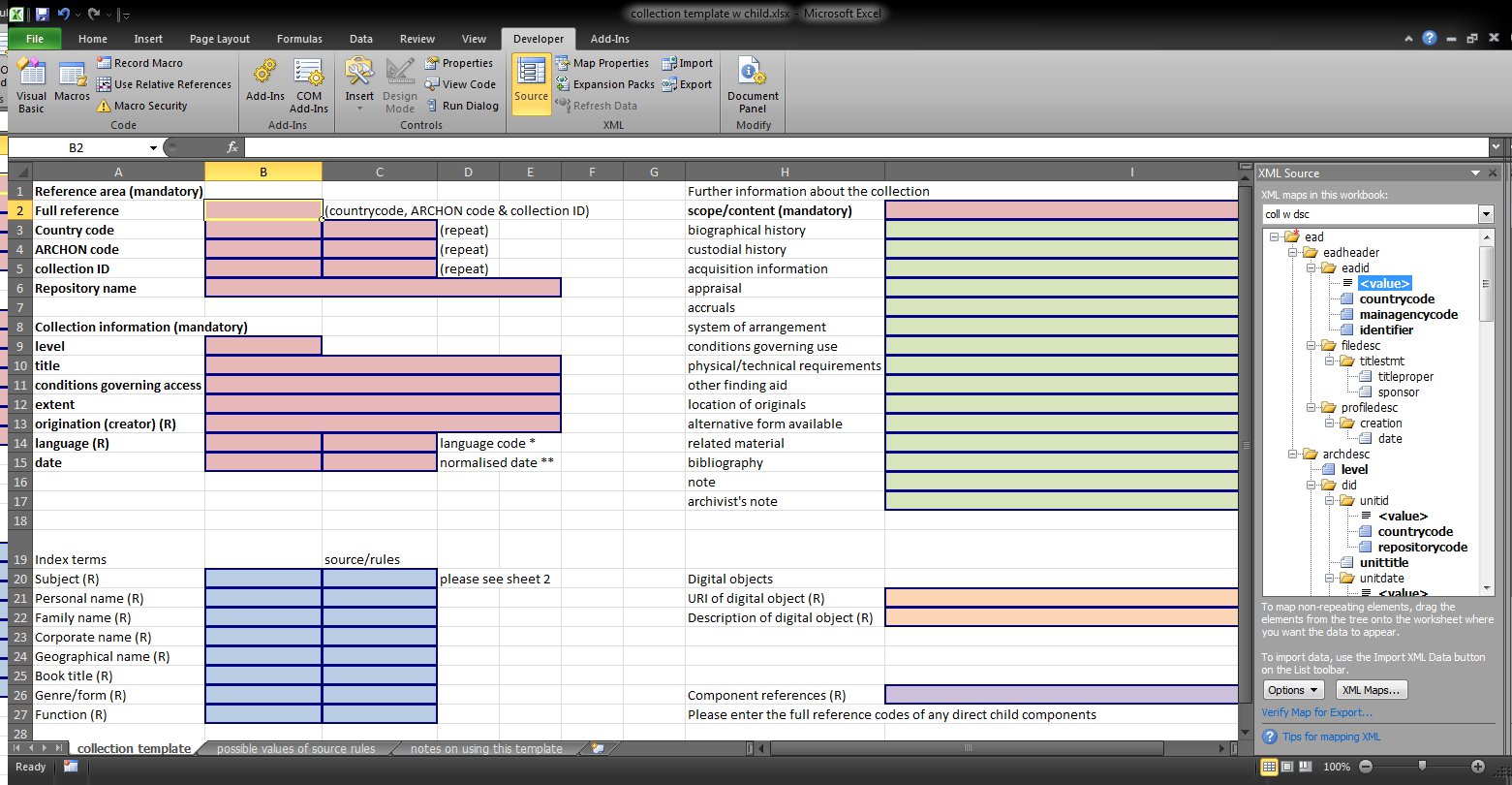

To get started with using XML in Excel, you need to have the XML add-in installed (it says 2003, but will work with other versions) and then make sure you can see the ‘developer’ tab – if you can’t, it’s under options -> customize ribbon.

While it’s hard (in retrospect) to remember all of the stages I went through in the trial-and-error, I know I started by trying to create an XSD (XML schema file) from in-Excel data entry. It failed. I tried importing the EAD.xsd – which just failed, silently (no error messages- no messages at all).

I was also concerned that the official EAD.xsd was too complicated for my (and our users’) needs – for instance, this project didn’t require lists of enumeration values. I needed something a bit simpler – and I’d already figured out that Excel couldn’t handle multi-level descriptions – so I needed to start with something collection-level only, too.

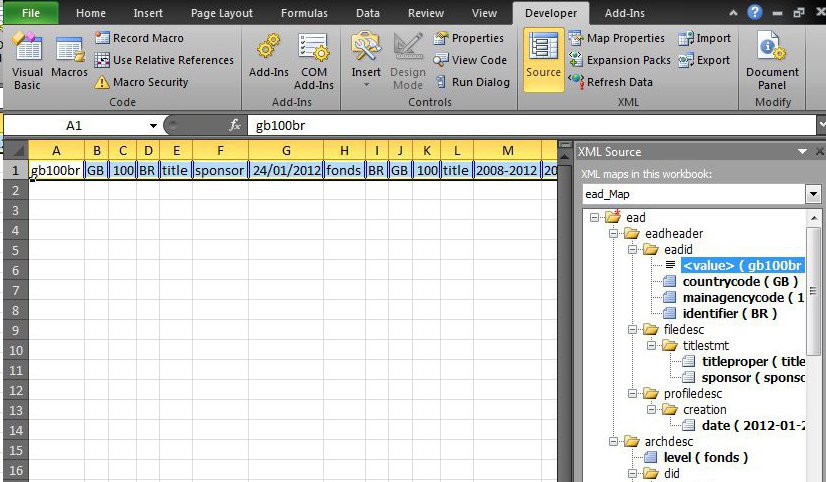

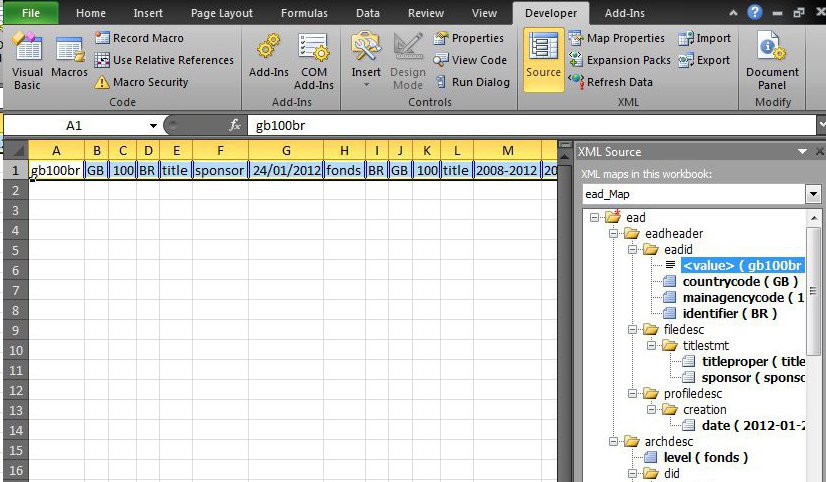

I created a basic EAD collection-level description in the Archives Hub EAD Editor, saved it as XML, removed the DTD declaration (not allowed in Excel), and imported it (using developer -> xml -> import). Clicking on ‘source’ in the developer XML tab then shows you the XML fields.

You can then export this map as an XSD, creating your XML schema. Of course, it wasn’t that easy. This is where denormalised data cropped up – and stopped me from exporting. I have to admit, I’m still not entirely sure what exactly denormalised data is – and given definitions such as:

A denormalised data model is not the same as a data model that has not been normalised, and denormalisation should only take place after a satisfactory level of normalisation has taken place and that any required constraints and/or rules have been created to deal with the inherent anomalies in the design. For example, all the relations are in third normal form and any relations with join and multi-valued dependencies are handled appropriately.

(from the usually introductory-friendly Wikipedia)

I’m not sure I’ll ever find out (if you have a really good explanation, please do comment!). But what I did find out was what it meant for me in the context of this XML mapping: no repeated fields. EAD allows for repeated fields – for instance, multiple subjects would be encoded as:

<controlaccess> <subject>subject</subject><subject>subject 2</subject></controlaccess>

Try to import that into Excel, and you get, well, a mess. The whole description appears twice – once with subject, and once with subject 2. And if you try to export the schema, you get the error message that the map is not exportable because it contains denormalized data.

For this reason, Excel won’t support hierarchy. In EAD, the same fields are repeated at component level as at collection-level, just inside a different wrapper. If you thought it got messy when you add a single repeated field, just imaging having anything up to several thousand…

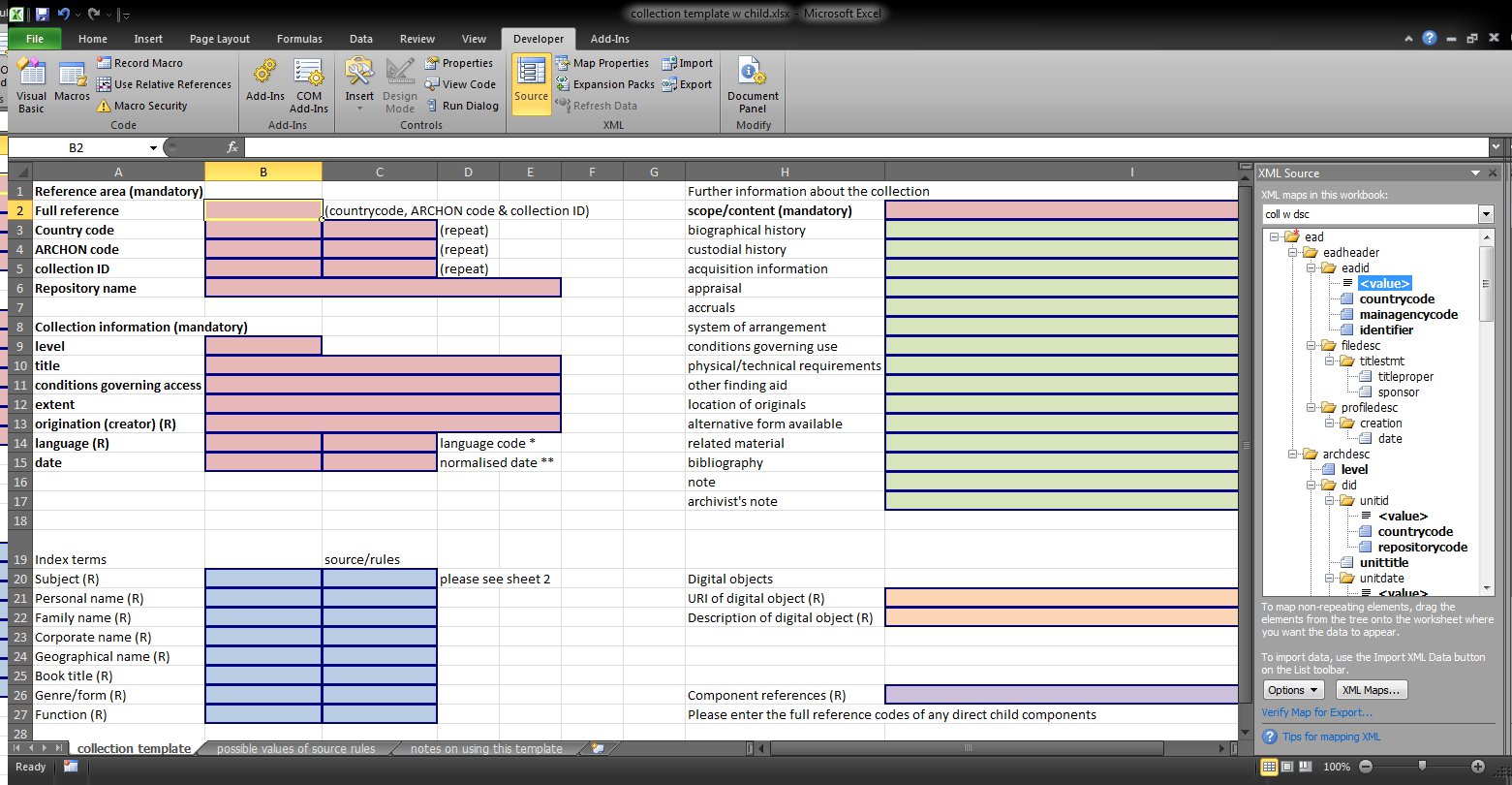

So, strip everything down to a single instance (which means separating collection and component level into different spreadsheets), and you have an XSD which will export (follow instructions in step 4 of that link – if you get a VBA error, debug instructions are in step 2). Hurrah! But how to make it useable?

Well, you have to put it back into Excel, and map the XML fields to Excel cells. This was tedious, but achievably tedious rather than crawling-through-help-forums tedious. Open up a new Excel document, click on ‘source’, and choose your shiny new XSD. This will give you a list of all the fields, in the right-hand pane. Mapping them to cells is simply a case of drag-and-drop – once you’ve mapped a field to a cell, that cell will be outlined in blue (as long as the source pane is showing). There’s an option to have Excel auto-label your fields with the content of the XML tag, but I decided that wouldn’t give the user-friendly interface I wanted, so I labelled them myself. Then colour-coded them. The result?

I had to tweak the exported XSD a little to allow for a field in which users can enter the reference codes of any components. This was my first experiences of hand-coding any of an XML schema, and it took a few tries to get right! But I managed to add and map the <dsc> and <c> elements:

<xsd:element minOccurs=”0″ nillable=”true” name=”dsc” form=”unqualified”>

<xsd:complexType>

<xsd:sequence minOccurs=”0″>

<xsd:element minOccurs=”0″ nillable=”true” type=”xsd:string” name=”c” form=”unqualified”/>

</xsd:sequence>

</xsd:complexType>

</xsd:element>

(If I wanted to play with the XSD a bit more, I guess I could make mandatory fields really mandatory, by fiddling with the minOccurs and/or nillable attributes, but I haven’t worked up the courage yet…)

This allows users to enter the reference codes of parent/child descriptions. Each component needs its own spreadsheet, and its own XML export. These are then run through a script by our programmer, which will use these parent/child references to create a single, hierarchical description. Theoretically, anyway – we haven’t been able to do much testing on it yet, and we’re not sure how well it will cope with components that are more than a level or two deep.

Remember denormalised data, and how you can’t have repeated fields? Obviously we can’t tell contributors that they can only have a single subject for each description! So in repeatable fields, multiple entries are pipe | delimited, so we can split them, eg:

<controlaccess><subject>subject 1|subject2|subject3</subject></controlaccess>

to

<controlaccess><subject>subject1</subject><subject>subject2</subject><subject>subject3</subject></controlaccess>

If users enter their subject sources in the same order, they’ll be matched up as attributes to the correct subject. The script also removes any empty fields (valid XML, but they break the EAD Editor), and adds the special Archives Hub mark-up for access points (used to distinguish between eg surname and forename in a personal name, and handy for linked data).

And there we are: a description, created in Excel, that’s valid EAD. We’re still in the process of testing the template, and making sure that it’s robust and meets users’ needs. If you’d like to be involved with testing, please get in touch.

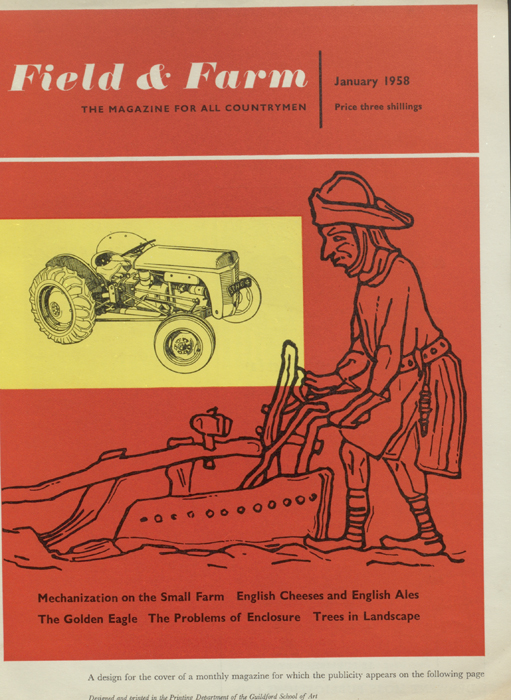

![Guildford School of Art, undated [1970s]](http://blog.mimas.ac.uk/archiveshub/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2013/08/Guildford-School-of-Art-undated-1970s.jpg)