Introduction

As part of our Exploring British Design project we are organising workshops for researchers, aiming to understand more about their approaches to research, and their understanding and use of archives. Our intention is to create an interface that reflects user requirements and, potentially, explores ideas that we gather from our workshops.

Of course, we can only hope to engage with a very small selection of researchers in this way, but our first workshop at Brighton Design Archive showed us just how valuable this kind of face-to-face communication can be.

We gathered together a small group of 7 postgraduate design students. We divided them into 4 groups of 2 researchers and a lone researcher, and we asked them to undertake 2 exercises. This post is about the first exercise and follow up discussion. For this exercise, we presented each group with an event, person or building:

The Festival of Britain, 1951

Black Eyes and Lemonade Exhibition, Whitechapel Art Gallery, 1951

Natasha Kroll (1912-2004)

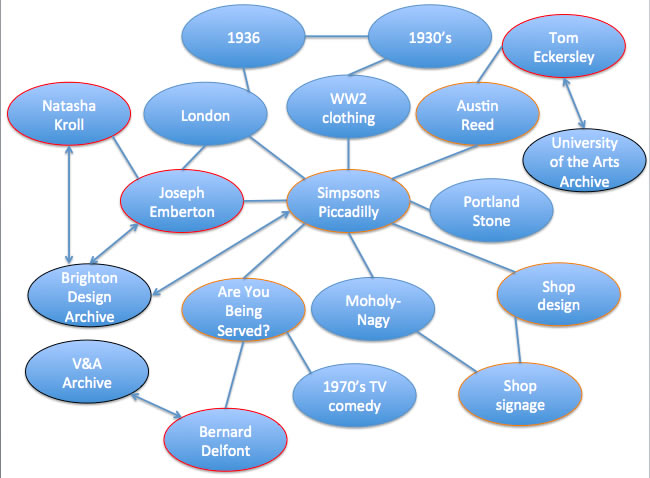

Simposons of Piccadilly, London

We gave each group a large piece of paper, and simply asked them to discuss and chart their research paths around the subject they had been given. Each group was joined by a facilitator, who was not there to lead in any way, but just to clarify where necessary, listen to the students and make notes.

Case Study

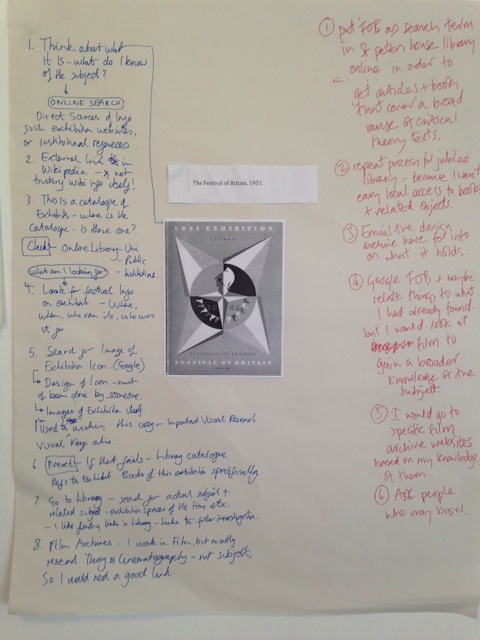

I worked with two design students, Richard and Caroline, both postgraduate students researching aspects of design at The University of Brighton. They were looking at the subject of the Festival of Britain (FoB). It fascinated me that even when they were talking about how to represent their research paths, one instinctively went to list their methods, the other to draw theirs, in a more graphic kind of mind map. It was an immediate indication of how people think differently. They ended up using the listing method (see left).

The above represents the research paths of Richard and Caroline. It became clear early on that they would take somewhat different paths, although they went on to agree about many of the principles of research. Caroline immediately said that she would go to the University library first of all and then probably the central library in Brighton. It is her habit to start with the library, mainly because she likes to think locally before casting the net wider, she prefers the physicality of the resources to the virtual environment of the Web. She likes the opportunity to browse, and to consider the critical theory that is written around the subject as a starting point. Caroline prefers to go to a library or archive and take pictures of resources, so that she can then work through them at her leisure. She talked about the importance of being able to take pictures, in order to be able to study sources at her leisure, and how high charges for the use of digital cameras can inhibit research.

Richard started with an online search. He thought about the sort of websites that he would gravitate towards – sites that were directly about the topic, such as an exhibition website. He referred to Wikipedia early on, but saw it as a potential starting place to find links to useful websites, through the external links that it includes, rather than using the content of Wikipedia articles.

Richard took a very visual approach. He focused in on the FoB logo (we used this as a representation of the Festival) and thought about researching that. He also talked about whether the FoB might have been an exhibition that showcased design, and liked the idea of an object-based approach, researching things such as furniture or domestic objects that might have been part of the exhibition. It was clear that his approach was based upon his own interests and background as a film maker. He focused on what interested and excited him; the more visual aspects including the concrete things that could be seen, rather than thinking in a text-based way.

Caroline had previous experience of working in an archive, and her approach reflected this, as well as a more text-based way of thinking. She talked about a preference for being in control of her research, so using familiar routes was preferable. She would email the Design Archives at Brighton, but that was not top of the list because it was more of an unknown quantity than the library that she was used to. Maybe because she has worked in an archive, she referred to using film archives for her research; whereas Richard, although a film maker, did not think of this so readily. Past experience was clearly important here.

Both researchers saw the library as a place for serendipitous research. They agreed that this browsing approach was more effective in a library than online. They were clearly attracted to the idea of searching the library shelves, and discovering sources that they had not known about. I asked why they felt that this was more effective than an online exploration of resources. It seemed to be partly to do with the dependency of the physical environment and also because they felt that the choice of search term online has a substantial effect on what is, and isn’t, found.

Both researchers were also very focused on issues of trust; both very much of opinion that they would assess their sources in terms of provenance and authorship.

In addition, they liked the idea of being able to search by user-generated tags and to have the ability to add tags to content.

General Discussion

In the general discussion some of the point made in the case study were reinforced. In summary:

Participants found the exercise easy to do. It was not hard to think about how they would research the topics they were given. They found it interesting to reflect on their research paths and to share this with others.

For one other participant the library was the first port of call, but the majority started online.

Some took a more historical approach, others a much more narrative and story-based approach. There were different emphases, which seemed to be borne out of personality, experiences and preferences. For example, some thought more about the ordering of the evidence, others thought more about what was visually stimulating.

It was therefore clear that different researchers took different approaches based on what they were drawn to, which usually reflected their interests and strengths.

There was a strong feeling about trust being vital when assessing sources. Knowing the provenance of an article or piece of writing was essential.

The participants agreed that putting time and effort into gathering evidence is part of the enjoyment of research. One mentioned the idea that ‘a bit of pain’ makes the end result all the more rewarding! They were taken aback at the idea that that discovery services feel pressured to constantly simplify in order to ensure that we meet researchers’ needs. They understood that research is a skill and a process that takes time and effort (although, of course, this may not be how the majority of undergraduates or more inexperienced researchers feel). Certainly they agreed that information must not be withheld, it must be accessible. We (service providers) need to provide signposts, to allow researchers to take their own paths. There was discussion about ‘sleuthing’ as part of the research process, and trying unorthodox routes, as chance discoveries may be made. But there was consensus that researchers do not need or wish to be nannnied!

All researchers did use Google at some point….usually using it to start their search. Funnily enough, some participants had quite long discussions about what they would do, before they realised they would actually have gone to Google first of all. It is so common now, that most people don’t think about it. It seemed to operate very much as a as a starting point, from where the researchers would go to sites, assess their worth and ensure that the information was trustworthy.

[There will be follow up posts to this, providing more information about our researcher workshops, summarising the second activity, which was more focused on archive sources, and continuing to document our Exploring British Design project.]